“I would never disrespect a human being enough to decide that we can change something through comedy.”

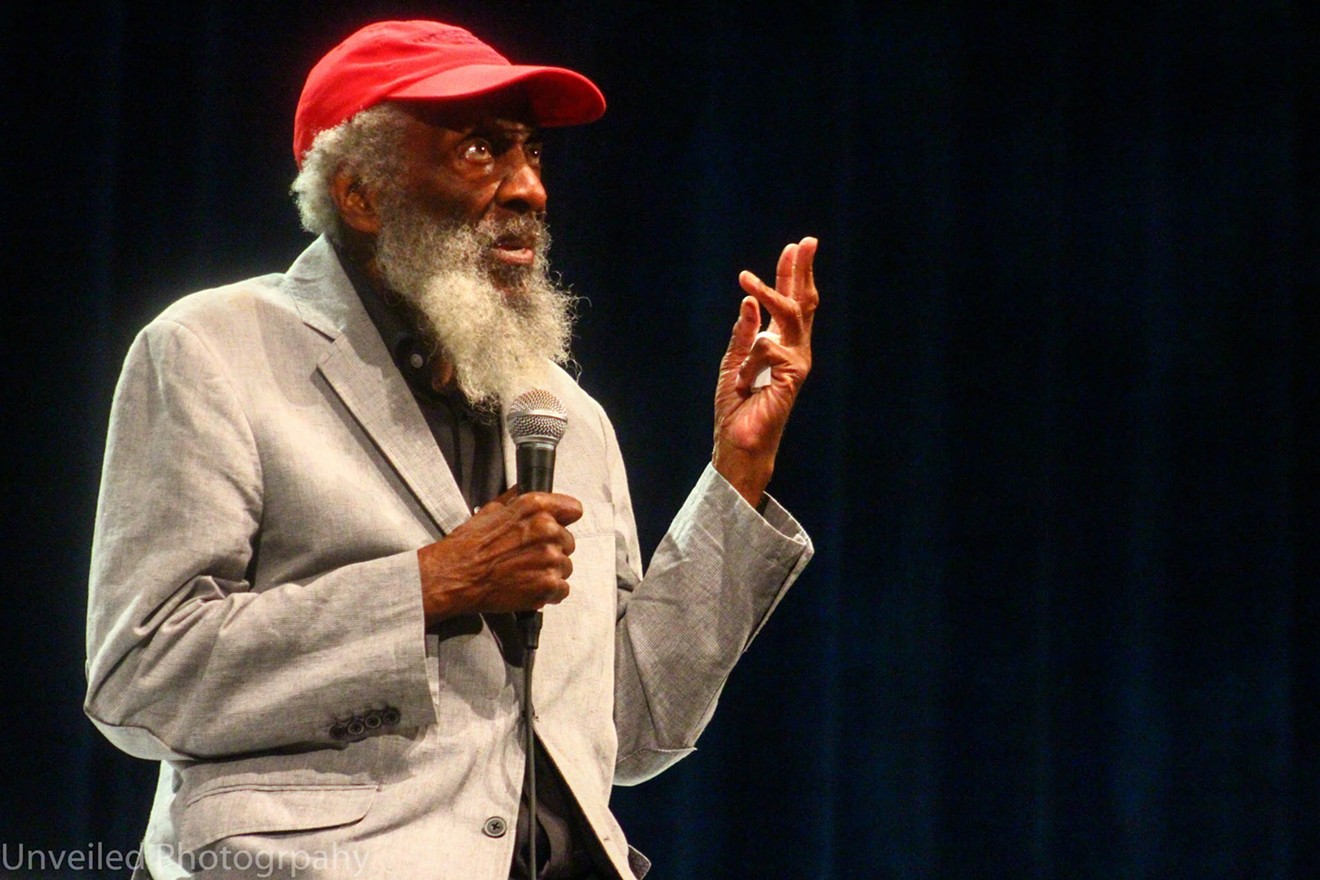

That’s the mantra of one of stand-up comedy’s true founding fathers, Dick Gregory. This week the writer, actor and civil-rights leader will be dropping by for his near-annual visit to the Houston Improv, featuring two nights of jokes and information Tuesday and Wednesday. “I read about a thousand dollars worth of newspapers every ten days,” the comic shares. “I don’t read ’em because I believe ’em…I read them looking for the cracks in the fabric.”

Speaking on the medium he helped develop, the 85-year-old oscillates from modest to almost dismissive of his legacy. “America has been through all the major wars since she was born, and she never took comics or entertainers or athletes to the front line,” he points out, speaking both fast and focused.

“I never had no idea I’d be an entertainer, or athlete,” Gregory admits, referring to his successes as a high-school runner. “But I had no intentions; that was just how the universe flowed.” While Gregory’s duration in cross country was short-lived, the era of his comedy has been going strong since the mid-'50s. “Now, I was probably the No. 1 comedian. Though most white folks said I was probably between 1 and 100, I don’t need to be validated by y’all. Y’all don’t even know me.”

His early days on the stage were difficult, the comic remembers, as the issues holding him back seemed both cultural and systematic. “A negro couldn’t work a white nightclub, not only in the South, but anywhere in America," Gregory says. "So consequently, you could sing, you could dance, you could smile, you could buck your teeth. But they wouldn’t let a black person stand flat-footed and talk, ’cause then they’d know how brilliant you are.”

Upon reflection, the legend credits another innovator for the opportunity to break into mainstream white America.

“Not until Hugh Hefner brought me in the Playboy Club had a black comic worked a white nightclub," Gregory recounts. "And after that, the door was opened. They found out who we were, and the genius we were. That was Hef who opened that door.”

Much of the black pop culture that trickled into the white consciousness during the ’60s can be credited to the Playboy founder, argues Gregory. “We owe a lot of black stand-up to him,” he says. “White stand-up always worked clubs, and they always thought they was funny…[but] when the only Pepsi cola you can get is one, they all taste the same,” he quips with a laugh.

In times of national peril, America has often turned to humorists to ease the burden of divisiveness. And thankfully, Dick has a lot to say about Don. “What’s happening with Trump went into motion in 1930. You heard War of the Worlds?” he asks, referring to the Orson Welles radio broadcast that led to pandemonium as middle America believed the country was being invaded by aliens. “People heard that and start killing their families.”

Gregory believes Trump’s estimated $3.5 billion net worth is misleading. “Nobody can say the things he say; he ain’t got no money,” he claims. “If you or me apply for a garbage job in Houston, before we can get it, we got to bring in our last year’s tax return. Here’s a man running for president and he ain’t got no tax returns? He ain’t the fool, we the fool.”

“The Shadow That Scares Me, that’s what we got now," he says. "I didn’t know the name of the person they was gonna use, but Trump ain’t nothing but a shadow.” Gregory even questions the legitimacy of the president’s father, Fred Trump, and his dealing in postwar New York City.

“They said he was in housing – but back then, the mob in New York owned the housing," he says. "And they would kill judges, cops, police chiefs, anything they want to do. Trump’s daddy is not listed. This whole thing is just a game.”

Race relations have always been a centerpiece of Gregory’s material. His comments are direct and pointed, offering corrective laughter at both the subtle and not-so-subtle forms of discrimination he’s faced since childhood. “When they decided that no longer would the word ‘nigger’ be used, do you know there wasn’t one black person in the meeting when that decision was made?” he notes. “Not the NAACP, not the Urban League, not Sharpton, and nobody complained?”

As the comic explains, he aims to divide people not into black or white but into three less-obvious categories. “There are two types of white folks,” he sets up. “’Cause white ain’t a color, it’s an attitude. And if you ain’t got trillions of dollars in the bank, you can’t have the attitude. If you talk to white folks about this, they don’t even know what you talkin’ bout. They think they white, but they not. They’re just another upscale class of a Negro, and don’t even know it.”

Another hang-up for the comic is language, a topic frequented by many comics of his generation, including Bill Cosby, George Carlin and Richard Pryor. “You have black folks asked: ‘How come you speak such bad English?’ We want to hide and try and [I say] ‘No, white boy! Here’s why I talk bad English, ’cause you stole me.’ [When you] brought me here, I was only speaking pure Swahili. I learnt my English from listening to you! I’ve been talking like you ever since. But yet and still, we silly enough that we want to apologize for talkin’ bad. But when you go back to Great Britain, they talk like the Queen talks. That’s something to think about.”

Though he decided against a leap into the movies, Mr. Gregory has plenty of thoughts on Hollywood. After he was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2015, Gregory’s acceptance speech was a simple question: What took so long? “I know, I been a bad boy,” he falsely pines. “I ain’t never had sex with a white woman and I ain’t never smoked the reefer. And black sisters, don’t you clap. I ain’t never slept with a white woman, not because of my loyalty to you, but I’m scared of ’em. I went to the movies as a kid — Wolfman, Frankenstein, Dracula – all of them came out of a white woman’s belly and think a few of them are still up there, I just don’t know which ones,” he guffaws.

Gregory also blasts fellow comics, including his St. Louis brother Cedric the Entertainer. “You take a thug punk like Cedric [in] that first movie Barbershop. Here’s what Cedric said: ‘Martin Luther King wasn’t nothing but a punk, and Rosa Parks didn’t do nothing great; she was just too tired to wave her big, fat black ass.’ You know a white boy wrote that, cause they see all asses as the same color.”

Nothing seems to scare the social critic after his 60-plus years in the public eye, least of all hecklers. “I know one thing: Nobody ever comes to a nightclub to see you die…less it’s a wife or somebody you misuse,” he says. “When I go there, I know what this audience is, they come to hear me.”

Recalling one of his great triumphs under pressure, Gregory seems ebullient. “I know back in the old days, a bunch of rednecks might come to mess up the show. One day, I was in this little town in Indiana, [and] a white boy said: ‘All right, that’s enough, nigger.’ Now, people came to see me — white folks, black folks — they came to see me. So I’ma let this cracker mess up the night? So I say, ‘You hear what the white boy said? He called The Lone Ranger’s horse…Trigger.’ And everybody laughs.”

He smiles upon the retelling. “And that’s how you handle it. Listen to the rhythm, listen to the floor.”

Beyond comedy, Gregory has spent a life battling injustice and corruption. During the Civil Rights Movement, Gregory marched against segregation, organized sit-ins and took fights all the way up to the Supreme Court. “When you stop and think about what I found when I joined King and that movement, that thing that came over me which was far greater than being a comedian or a great athlete," he says. "I still don’t understand – and I probably should. You think about all those folks in the summer took their children to Disneyland to see a rat…but haven’t been to King’s grave or the Tomb. Had he not done what he did, they wouldn’t even be welcome in Orlando.”

Asked if he had any comedy role models, people who influenced him to go into his profession, Gregory laughed. “Out of all the people who ever lived, my idol is John Brown, a white man who did Harpers Ferry," he says. "Had he not raided Harpers Ferry, the planet wouldn’t be the same.”

For context: In 1859, the fervent abolitionist Brown and a party of 22 initiated a slave revolt by attempting to seize a Virginia armory. “He went into Harpers Ferry and killed 13 people, the 12 jurors and the judge,” says Gregory. “I’ll go anywhere for liberation, but I won’t take my children with me. He did! A white man! Took his children! They arrested him and sentenced him to hang.”

As tribute to John Brown and his fallen insurgents, the comic’s developed a ritual. “Every birthday of mine, I go to Harpers Ferry and I walk from the courtroom to the street, like John Brown did," Gregory says. "I get in the street, I turn left, I walk three blocks, I turn right, I walk four blocks and that tree they hanged him on is still there. I go hug the tree.

"When they were taking him over to the tree, some redneck yelled, ‘How you feel now, nigger lover?’" Gregory continues. "And he said, ‘If what I was doing, I was doing for rich white men, I’d be your hero.’ And as he got to the top of the stairs to be hanged, he says, ‘Oh, by the way, I talked to God last night…and he told me that you all have missed the last chance of freeing the Negro slave. And because of this, you’re gonna see one of the biggest bloodbaths in the history of the planet.” He told them that, and then they hanged him.”

Painting the scene, Gregory describes the final journey of Brown and the Virginians who feared the abolitionist would become a martyr. “Black men came and shoulder to shoulder, from Harpers Ferry, Virginia, to upstate New York where they buried him; [they] lined that road to say to the white folks, ‘Come out here. You come out here if you strong enough,’" he says.

"And that’s how he made it back," Gregory adds. "And had that not happened, the world would be different, different, different. So that’s my loyalty — to those folks who pulled that off. To what they did when they didn’t have to.”

With time for one more final thought, Gregory proudly states, “Who you ever heard being liberated by some jokes?”

Dick Gregory performs 8 p.m. March 28 and 29 at Houston Improv, 7620 Katy Freeway. For information, call 713-333-8800 or visit improvhouston.com. $30-40.