Since his low-key, low-expectations debut, the Jeff Bridges diversion Crazy Heart (2009), Scott Cooper has specialized in thoughtful, actor-driven, for-adults Hollywood genre fare: a Deer Hunter–lite Rust Belt saga of brothers and blood (2013’s Out of the Furnace); a vicious tale of Boston gangsterdom (2015’s Black Mass). This is an underserved sphere. But Cooper has yet to elevate his sensibility beyond a choked, self-inhibiting intensity, as evidenced by the dour non-arc given to a character like Master Sgt. Thomas Metz (Rory Cochrane) from his latest, Hostiles.

Metz is introduced knocking back whiskey in near-pitch-darkness, his Paul Bunyan facial hair dripping with booze as he growls through a story about man’s capacity for violence. Later, he’ll talk about man’s capacity for violence at dusk, with a fresh-faced West Point grad (Jesse Plemons) who’s just killed his first; here, Cooper directs Cochrane to angle his hardened face away from the camera, toward the horizon, as if the character’s words were too sacred to be confronted directly. And then, in one of his final scenes, Metz — having seemingly exhausted all his anecdotes about man’s capacity for violence — simply stands in a torrential downpour, raindrops swimming across his face, and states, “I don’t feel anything.” Each of these exchanges, in the moment, appears dramatically effective and powerfully performed, but consider them all at once and you might wonder what the hell the pre-stultifying-existential-malaise version of this character could have looked like. With each additional appearance, Metz seems less like a person worth investing in than a sentient beard chiming in to remind us that we’re watching a morally tortured American western.

Army Capt. Joseph Blocker (Christian Bale), the hero of Hostiles — which is set in 1892 — suffers from a different kind of emotional disjointedness. Early beats at New Mexico’s Fort Berringer prison establish the soon-to-retire officer’s festering bigotry: “like ants, they just keep comin’,” he angry-mumbles in reference to a group of Native Americans he and his team have just corralled and brought in. Soon, Blocker’s boss, Col. Abraham Biggs (a dignifiedly coiffed Stephen Lang), saddles him with a most unwelcome task: escorting a cancer-stricken Cheyenne war chief, Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi), from Fort Berringer, where he and his family have been incarcerated for seven years, to their home, the Valley of the Bears, in Montana.

The threat of a slashed pension encourages Blocker to cooperate, but so enraged is he by the prospect of the assignment — he has seen several close friends die, in heinous fashion, at the hands of Yellow Hawk — that he retreats alone to an open field and reaches for the gun in his holster, as if to take his own life. Bale, as Blocker, falls to his knees and screams to the high heavens in agony, but he’s drowned out by the escalatingly foreboding Max Richter score on the soundtrack. Blocker’s racial anomie (“wretched savages”) had previously been straightforward; here, Cooper at first leads viewers that the man hates Native Americans so much he would sooner shoot himself in honor of that hatred rather than simply do his job.

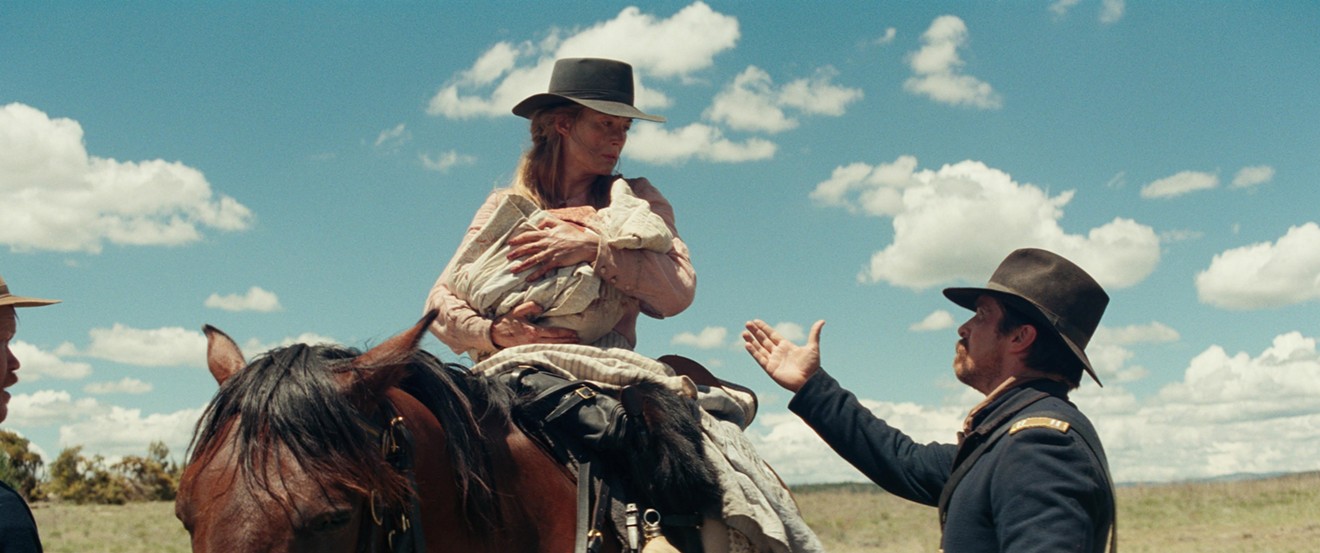

This surge of internal agony seems intended to pulse throughout the movie’s gruesome state-crossing trek, but Bale, in the part, is much less caricature-adjacent in the lighter beats, the ones that hint at the monstrous Blocker’s possible redemption. The actor’s channeling of the officer’s air of fierce professionalism leads to moments of endearing workaday comedy, as when Blocker takes roll call and unleashes his in-your-face intensity on a pair of plainly overwhelmed greenhorn subordinates: the West Point grad (Plemons) responsible for meat, raisins, sugar, pickles; the befuddled teenage Frenchman (Timothee Chalamet) with little command of English. Later, the team comes across a homestead that has been attacked and burned nearly to ashes; inside is Rosalee Quaid (Rosamund Pike), the sole survivor, who still has two of her babies wrapped in blankets (“they’re sleeping,” she insists). Blocker is instantly, remarkably attentive to the truth of the situation, telling his colleagues to quiet their footsteps in consideration of the children — thereby satisfying her comforting fantasy.

Bale confidently strikes these notes of hard-edged sensitivity, inserting respectfully gruff “ma’am”s between offers of warmth, water, blankets, food. Reconciling this figure of natural empathy and mesmerizing focus with the previous wobbling brute who reflexively emits “bitches” and “bastards” is a bizarre task; the disjunction seems less a sign of a protagonist with complexly contradictory sympathies than a reflection of the psychological fuzziness of Blocker’s sketched-in backstory. When Cooper wants to humanize Blocker, we get nicely unhurried scenes, like the bedside one in which Blocker is brought to clenched tears at the sight of his bandaged, bullet-ridden longtime associate, Cpl. Henry Woodson (Jonathan Majors); when Cooper wants to remind us of the man’s flaws, we get a Max Richter eruption or a dirge of exposition, as with the fractional cameo from Bill Camp, whose journalist character helpfully announces that Blocker has taken “more scalps than Sitting Bull himself.”

In Black Mass, Cooper shot the pulpy Whitey Bulger murders with an awkward sobriety, as if he were intruding on Sunday Mass — he seemed not to understand the movie his giddy, aiming-for-the-rafters star Johnny Depp was intending to make. With Hostiles, he hews a little closer to his material’s nastiness, but the predominant sensation is still a nearly unremitting aura of brooding seriousness. (It’s the third straight movie on which Cooper has collaborated with Masanobu Takayanagi, a gifted cinematographer so adept at muted majesty that he literally shot The Grey.) Near the end of that first scene with Pike’s Rosalee Quaid, her character’s house a blackened, bloodied shell of its former self, Majors’ Woodson surveys the wreckage and remarks, “God Almighty.” It’s a line that doubles as a guiding principle for the movie itself, nearly every solemn, violent, plodding scene of which seems intended to inspire the viewer to lean back in their chair and reflect: God Almighty.

Cooper can’t even be bothered to have some harmless fun with the casting of Ryan Bingham — the musician behind the Oscar-winning song “The Weary Kind,” from Crazy Heart — as a soldier who becomes added to Blocker’s detail. In one scene, Bingham gets to sing maybe three or four lines of a song; to hang back for a minute and let him perform an entire tune would be to disrespect the gravity of the American frontier — and, just maybe, to make a movie with some genuine surprises.

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

- Sign out

Christian Bale and Hostiles Brood Their Way Through the Frontier

Danny King December 15, 2017 12:23PM

Rosamund Pike (left) plays Rosalee Quaid, the sole survivor of an attack on her 1892 homestead who is aided by Christian Bale's Army Capt. Joseph Blocker in Hostiles.

Lorey Sebastian/Courtesy of Yellow Hawk, Inc.

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]

KEEP THE HOUSTON PRESS FREE...

Since we started the Houston Press, it has been defined as the free, independent voice of Houston, and we'd like to keep it that way. With local media under siege, it's more important than ever for us to rally support behind funding our local journalism. You can help by participating in our "I Support" program, allowing us to keep offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food and culture with no paywalls.

Danny King

Trending Film

- International Film Festival 2000

- It’s Sadly Kind of Perfect That New Season of GLOW Is Stolen by Marc Maron

- Made in Houston

-

Sponsored Content From: [%sponsoredBy%]

[%title%]

Don't Miss Out

SIGN UP for the latest

news, free stuff and more!

Become a member to support the independent voice of Houston

and help keep the future of the Houston Press FREE

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

The Houston Press may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Houston Press, LP. All rights reserved.