By Nicholas Reynolds

William Morrow, 384 pp., $27.99

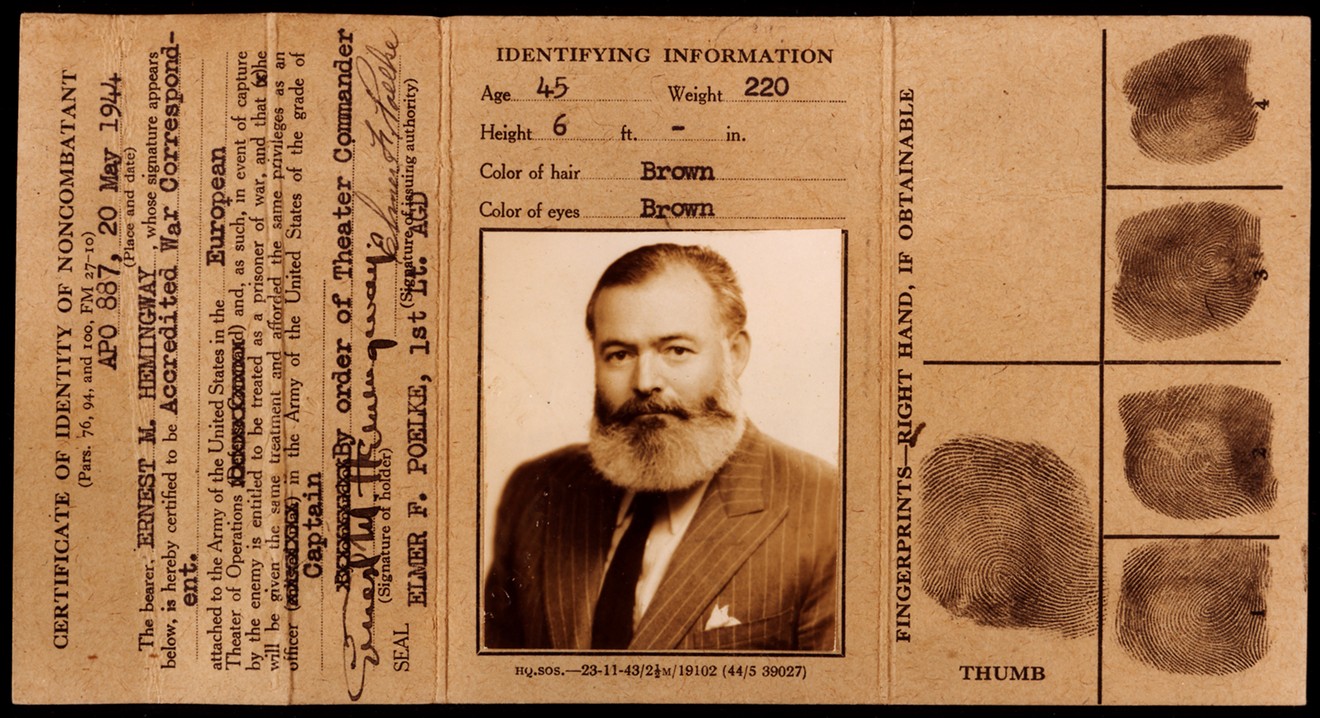

By this point in literary history, there have been more words spilled about Papa than he ever pecked out on typewriters throughout his life and global adventures. Two new biographical entries focus on specific chapters – with one breaking new ground by highlighting previously hidden government documents.

Hemingway’s novels were often set in

Hemingway would serve as both an official and unofficial information-gatherer and reporter during many conflicts around the world over the decades. That began during the Spanish Civil War, when he supported the Communists in both writing and deeds (though, with anti-Fascism and not anti-Democracy leanings as his inspiration).

The book’s main focus is how Hemingway was even recruited by an agent from the Soviet Union’s NKVD – a precursor to the KGB – while also providing information to Britain’s OSS and the U.S.’s FBI. And while Reynolds did not have access to KGB archives and the FBI files are “fragmentary,” the author clearly had influence and impact, even getting in over his head at times.

Some of Hemingway’s adventures, though, stretched reality even for a novel. During World War II, he actually put in a plan that got tacit approval for him to sail his fishing boat, the Pilar, off the coast of Cuba. Hoping to entice Nazi submarines to surface to seize or inspect the “fishing boat,” Hemingway and his trained team would then attack the Germans with hidden “bazookas, machine guns, and grenades,” hoping to lob one of the latter into an open U-Boat's hatch, blow up the vessel, and take out some Krauts.

In that same conflict, as a credentialed war correspondent, Hemingway would ferret out information from a wide circle of military personnel and civilians, even to the point of smuggling documents. And at least once, the real-life action figure would drop his pen and pick up a Thompson submachine gun, happily

Later in life, while making a mostly-permanent home in Cuba, Hemingway would support the aims of Fidel Castro in his successful attempt to overthrow the Batista government. The two met once when, after coming into power, Castro – seemingly legitimately – won a fishing tournament that the author sponsored, with Hemingway handing over a silver trophy to the bearded leader.

Castro, in turn, would tell Hemingway that he carried a copy of For Whom the Bell Tolls in his rucksack while hiding out in the mountains. But when Castro’s tone turned very anti-American – and the Bay of Pigs fiasco ensued – Hemingway and fourth wife Mary quietly slipped out of the country, leaving their home and belongings behind.

Conventional wisdom reports that a combination of depression, deteriorating health, and mental fatigue due partially to electro-shock treatments led Ernest Hemingway to take his own life with a shotgun blast to the head in 1961.

But, as Reynolds reveals most intriguingly here, the author was also paranoid that the FBI would come banging down his door at any minute after discovering his close relationship to and work for the Russians. That scenario was highly unlikely, but it’s a lasting legacy.

“The ultimate professional when it came to writing, in politics and intrigue, he was a gifted [but]

The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War

By James McGrath Morris

Da Capo Press, 288 pp., $27

They could not have been more different in temperament, interests, or lifestyle choices, but Hemingway and fellow writer John Dos Passos were tight frenemies for decades. They first met on a European battlefield during World War I, where both had volunteered to be ambulance drivers

And though they entered the conflict with a sense of schoolboys’ excitement and adventure, the horrors of real war made in impact on both. Their experiences infused their early novels, where Dos Passos actually had the earlier critical success. And Hemingway’s romantic relationship with the older nurse who cared for him after an injury-inspired A Farewell to Arms.

“Whereas Hemingway was egotistical, certain of himself, willing to get ahead at the expense of others,

Over the course of a nearly 20-year friendship, these two charter members of the “Lost Generation” of writers would be alternately close and estranged, or would praise and pick apart each other’s work, and debate and discuss over endless bottles of wine and cheese plates in homes, cafes and restaurants all over the world.

But they approached writing differently – Hemingway believing that literature should be a perfect representation of an imperfect world, while Dos Passos felt that writing without a greater political or social purpose was useless.

Politics, it seems, eventually drove the pair apart. Dos Passos had always wanted Hemingway to take a more political stance and was disappointed that he didn’t. But when he finally did with the Spanish Civil War – and Dos Passos had become disenchanted with socialism — the arguments grew more heated. They eventually fell out over a planned documentary the two had traveled to the country to make, their relationship never to recover.