When we talk with Stephanie Wittels Wachs, it’s a Friday morning. She apologizes in advance for the cartoons which might seep into our interview from the background. She’s turned on the television for her 4-year-old daughter, Iris, who already knows how to operate the Roku and has to shush her mom at least once while we’re discussing her new book, Everything Is Horrible and Wonderful: A Tragicomic Memoir of Genius, Heroin, Love, and Loss.

Iris isn’t actually feeling well, so Wachs deftly divides her attention between work and home over our longish chat. And, at some point, she’ll have to pack for a bi-coastal book tour, which is set to begin mere hours later on February 26, the day the book releases. Is this really a good time for us to talk, we ask?

“I’m used to multi-tasking. I’m comfortable that way. I like to live in that space,” she tells us, with an easy laugh.

Laughing and keeping busy aren’t just fortes for the Houston writer, they’ve been godsends for her and traits of her life, as well as her brother’s. Her brother is Harris Wittels, whose prolific but brief career in comedy came to an abrupt and unkind end almost three years to the day of our Friday morning conversation. Wittels was an actor, a comic and a writer whose talent and energy infused beloved television programs like Parks and Recreation, The Sarah Silverman Program and Master of None. He was only 30 when he died of a heroin overdose in February 2015. Everything Is Horrible and Wonderful,… details the tragedy, how Wachs and her family navigated the grief which followed and a whole lot more.

Before we discuss the book, we ask about Rec Room, the downtown Houston performance space she co-founded and oversees. She says its artists in residence are currently presenting its residency festival. The space’s third annual Beer and Ice Cream Social is slated for March 31. Plans are upstart but in the works for Harris Phest, which celebrates Wittels on his birthday each April.

She tells us the tour schedule. The day of the book’s release, she’s on Late Night with Seth Meyers in New York City. Two days later she’s in Los Angeles for a show and book signing organized by Sarah Silverman. Later in the week, she’s in San Francisco, then returns home for a Tuesday, March 6 event at Brazos Bookstore before heading to SXSW for a March 10 date.

“And then, I’m done,” she says, exhaling deeply, way before any of this actually happens. “And then, I have a baby.”

She’s 27 weeks pregnant with her second child when we chat.

“I never of my own volition was like, ‘I am now going to write a book.’ That’s why this whole thing is so bizarre. It happened but I felt so very out of control of it. I felt like I was kind of a passenger and this thing was kind of happening and I was a willing participant. It wasn’t the sort of thing I put a lot of taxing energy into. It sort of wrote itself.”

Only, of course, it didn’t. Wachs is a creative, but writing wasn’t her first choice. She’s an actress, with dozens of voice roles to her credit. She taught in the High School for Performing and Visual Arts’ theater program. She didn’t become a writer until after Harris’s death, when she needed an outlet to express her feelings and found it on the Medium publishing site. She wrote a piece called “The New Normal,” which wound up being a sort of template for the book. The essay is stark, somber, humorous and hopeful. Her literary agent saw it and convinced her to try writing a book over a year (“She knew I was in an emotionally kind of devastated place and that it might not happen but the way that I was coping with everything at the time was to write”). Her editor helped her develop a fuller book by asking for more words (“My response was, ‘You can fucking add ‘em because I’m done. I’m out of words, I have nothing more to say, I’m tapped out.’ She was such a brilliant editor that she was able to go through and really mark places that needed to be fleshed out”).

“Half of the book is written from the day that Harris died to the year after, in real time, in present tense. I talk to him in the book. That’s just about dealing with grief and getting through it and how to survive that horrible experience of loss,” she says. “And then, the other half of the book is really retracing my steps and going backwards. The part that goes backwards is the part where I’m trying to figure out how this happened, why this happened, what got us from there to here. Was it avoidable, what were the signs – when something really senseless happens, you know, you just try to make sense of it.”

The book is very personal but its universal themes on family, genius, addiction, death, grief and resolve run the spectrum, from everything that is horrible to all that is wonderful.

“The wonderful that’s in the book — and there’s a lot of fucking horrible in the book – but the wonderful is like, one, Harris is wonderful. Like, the most wonderful; so, there’s a lot in there about him and his genius and his comedy and our family and my daughter and my husband and all of the things that keep us going.”

At the time of Wittels’ death, it was imperative that his sister kept going.

“I had a one year old. I was like in a pit of hell, but I also had a baby to care for. When you have a baby who just wants to pick flowers and blow bubbles and swing at the park, it’s hard to just be completely immersed in sorrow, when you’re literally with somebody who’s discovering the world for the first time.”

The themes might be heady, but Wachs’ writing is direct and frequently funny. The humor isn’t a way to hook readers or soften the blow of the story's more difficult moments, it’s just a natural extension of who she and her family are. She said her father, who is a doctor, is “a stifled performer. He’s the weirdest dude, he’s just a bizarre person.” Her mother is an educator, who had Wachs enrolled in drama classes by the age of three. Their support set the tone for all that would come for her and Harris, she noted.

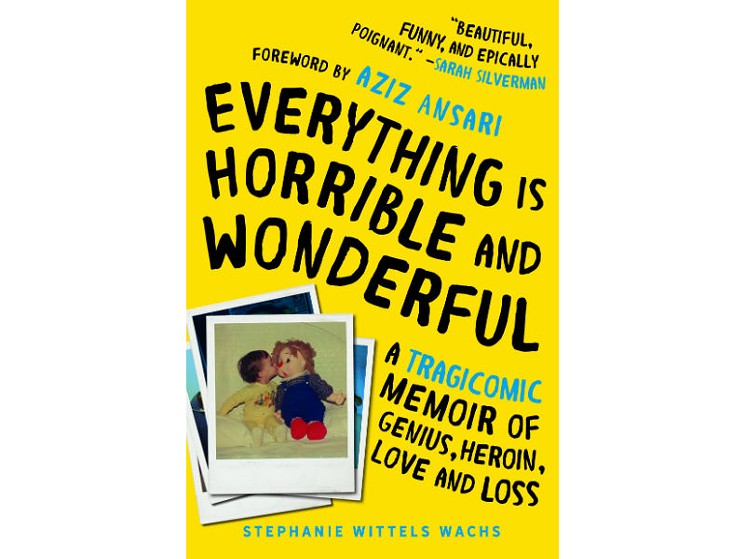

Wachs said she and Harris, pictured here, grew up in a supportive environment

Photo courtesy of Stephanie Wittels Wachs

“It was a funny house. Laughing was important, being funny was important. It was a weird place to live," she said. "They also just gave us a ton of freedom as individuals. There’s a lot of restrictions now people place on their children about TV. I certainly don’t in my house. We were allowed to watch 100 hours of TV if we wanted. We could do whatever we wanted, we could eat whatever we wanted, we didn’t have bedtimes, we could do whatever we wanted – it was like a real free-for-all.”

“Harris watched 70 million hours of TV growing up, that’s what he did and all these people that are like, ‘Oh, TV rots your brain,’ it’s like, well,.. it kind of made him awesome, it kind of made him who he was. He had like a comedic encyclopedia inside of his brain. I think that kind of freedom was part of what steered us in this direction.”

That built-in confidence never wavers, it seems. It’s what helped her narrate the audiobook version of Everything Is Horrible and Wonderful. Wachs has done voiceover work for more than 12 years. She hosts her own parenting podcast. But, she dreaded having to read the book in the booth.

“I did have to take many breaks to just weep and then pull myself back together and then come back to the mike. It was crazy to read it out loud. It was,…I don’t even have the words,” she said. “And, it’s amazing where in those moments your training just kicks in. You’re in this other mode and I was just kind of outside myself in a way, but then I would just get hit with some profound moment and I would just fucking lose it, fall apart.”

Wachs said the Medium posts helped her understand where the book was headed. Readers commented frequently on how she’d put into words something they were feeling or experiencing.

“People feel like they can relate to the story even if the details aren’t the same. There’s a feeling of unity that comes from that, that was something that I had no idea would happen or would make me feel – I’m not going to say better, because nothing was able to make me feel better – but it did make me feel less stranded on an island,” she said. “I think it’s just the most authentic expression that I’ll ever have and that’s what people are responding to – when people are honest or authentic or raw – that’s the part that’s like, ‘Oh, humanity, okay I’m into that. I like humanity, that feels good.”