Patty Waters’s back catalog isn’t all that impressive when viewed in a perfunctory manner. Two records, entitled Sings and College Tour, in the 1960s for the ESP-Disk label. Then absolutely nothing for basically 30 years.

But she’s a legend. One of the greatest in jazz and free-jazz history. And not just because of her enigmatic trajectory.

Sings and College Tour laid the foundation for vocal experimentalists. There might not be the Diamanda Galas material that we know, the Patti Smith we’ve heard, if not for Waters, who vanished almost as quickly as she appeared in the New York avant-garde scene by way of a tiny Iowa town.

“One really ought to hip oneself to the art of Patty Waters,” wrote Nick Tosches in Rolling Stone in 1971. “She is one of the best fucking singers alive.”

The thing is, fans have tried to hip themselves to more Patty Waters. We’ve tried, too. A lot. But other than a lyrical rendition of Ornette Coleman’s “hit single” “Lonely Woman” on Marzette Watts’s 1969 self-tiled album on Savoy Records, there hadn’t been anything else. The silence was more powerful than Waters’s blood-chilling screams on “Black is the Color of My True Love’s Hair” and “Wild is the Wind.”

Turns out, Waters’s rumored impenetrable privacy wasn’t all that impossible to pierce.

Since Waters’s emergence in the late 1990s, publications have zeroed in on the mystery of the small-town Midwestern girl who found her way to NYC performance spaces – which she shared with Charles Mingus, Chick Corea, and Bill Evans – and then went poof. Part of the reason for Waters’s silence boils down to moving to California to become a single mother to a son she had with Sun Ra Arkestra drummer Clifford Jarvis, who informed the songs about heartbreak on her records.

But what else contributed to her evacuation from music?

When Art Attack asked Waters, 72, what made her want to start performing again after so many years away, she paused for a moment.

“Well, I was invited,” says Waters by phone from her Santa Cruz, California home earlier this month. “It was easy to say ‘yes’ when I was invited.”

In other words, she had been available all of that time – 30 years! – but people weren’t asking her to play concerts. That is insane.

Whether or not this has been the real reason all of these years, fans of the reclusive Waters are thrilled she’s back. She grew up in Logan, Iowa (2010 census population: 1,534), located about 35 miles from Council Bluffs and Omaha, Nebraska, and only started performing because her mother put her on stage as a kid – masonic lodges, country clubs, places like that.

In high school, she sang at Offut Air Force Base in Omaha. “I have a newspaper clipping that says, ‘Patty is in high school, she’s getting good grades and she also sings,’” laughs Waters.

After high school, she traveled and lived all over. In Portland, Oregon, she sang at local clubs. In Vancouver, Washington, she performed at The Crown Room. In Los Angeles, she lived in an artist studio with up-and-coming performers. In Denver, she worked as a cocktail waitress at the Hilton.

In San Francisco, she sang at late-night jam sessions with touring musicians, including Miles Davis, who would head to the after-hours clubs following their official gigs. “Miles gave me some good advice,” says Waters. “He said, ‘Don’t be afraid and accent your strengths.’ It was good advice, I’ll never forget it.”

By 1964, she was in New York waiting tables on Wall Street and fine tuning the songs that would appear on Sings, her debut on Bernard Stollman’s fallacious label.

When JazzTimes scored an interview with Waters in 2004, she told the magazine that before and during the songwriting process, her parents disowned her over her interracial relationship with Clifford Jarvis. “They said I’d never loved them, I was never capable of love, that I would be poison to the family and not to come home,” Waters told James Gavin of JazzTimes.

The A side of the 1966 album is a collection of raw and real sad-girl songs, none more than three minutes in length, many about crushing heartbreak and unrequited love of the worst kind. (“But sad songs don’t make me feel sad,” Waters explained in JazzTimes. “I find beauty in them, joy.”) The stripped-away vignettes feature Waters on piano and singing in a style that mixes jazz techniques with dramatic hushes and well-timed silences.

The B side of Sings contains just one tune, a nearly 14-minute revamp of the sweetie pie folk song “Black is the Color of My True Love’s Hair.” Hear this eerie version piloted by Waters (who truly seems possessed), pianist Burton Greene, bassist Steve Tintweiss and percussionist Tom Price and you might never pair “sweetie pie” with this traditional song ever again.

Aside from Abbey Lincoln’s fiery venting on the Civil Rights anthem “Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace” from We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, nobody had screamed like that on a record. Not one person. Arguably, nobody has done it quite like that since. It still brings chills every time.

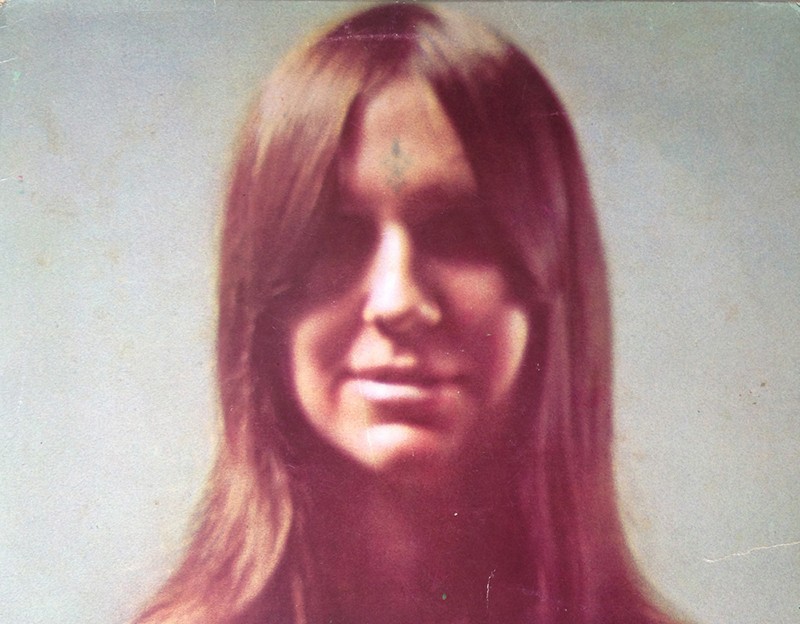

Another music landmark was staked into this strange planet with College Tour. When ESP procured a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, the label sent Waters, Greene, the Sun Ra Arkestra, Giuseppi Logan and Ran Blake on a tour of five New York state schools. The concert recordings, boasted by an LP jacket portrait of Waters that one reviewer likened to a Charles Manson Family girl, gets to the bottom of the unhinged with wordless singing, lullaby-like hums and hellish shrieks

“In the history of recorded music, there are certain artists who make groundbreaking emotional impact with only one or two statements, one or two albums. For many of us, that artist is Patty Waters,” says David Dove of Houston’s Nameless Sound.

“There are certain artists who, in a single recording, do something that has never been done before. But following that point in time, that something will be done many times again by many other people. Patty Waters is one of those artists. And sometimes these musical voices make these influential life-changing statements, and subsequently vanish from the public eye. They become enigmas, whose legend grows and grows in their absence,” says Dove.

For breaking the sound barrier, Waters received $350 for the original pressings and reissues of Sings and College Tour, according to the 2004 JazzTimes story.

Instead of paying rent with her (non-existent) royalties and concert work, Waters focused on raising her son — Andrew Miles Waters went on to become a championship surfer — and collecting college degrees. She attended the College of Marin and earned associate degrees in humanities and liberal arts and a bachelor’s in applied art. She stuck around northern California until 2000, moved to Hawaii for about five years and returned to Santa Cruz for good in 2005.

In between all of that, in 1996, Waters came of nowhere with a now out-of-print CD called Love Songs, a straight-ahead collection of jazz standards (“Summertime,” “My Foolish Heart,” “Mood Indigo”) featuring Waters, who's a big-time fan of Billie Holiday, and Jessica Williams on piano and synthesizer.

Since 1999, she’s performed far and few between at the Monterey Jazz Festival, the 2003 Vision Festival in New York City and the now defunct Le Weekend Jazz Festival in Stirling, Scotland. During the last few years, she’s played concerts in Copenhagen, The Netherlands, Sweden and London for a two-day residency at Cafe Oto — Waters says the live recordings from those December 2017 London gigs are slated for a digital-only release.

After performing Blank Forms Festival in Brooklyn on April 5, she’ll make her way to Houston for her Texas debut and then goes poof from us again. But it’s ok this time because she’s not forever gone like we had come to believe.

“We listen to a singularly radical expression like ‘Black is the Color of my True Love’s Hair,’ and we wonder: Who was this person? How and why did they do that? Where are they now? We don’t often have the real-time, in-the-flesh opportunity to encounter these mysterious figures," says Dove of Nameless Sound. "But Patty is back! And we have to see her, and we have to listen! She is no longer just the haunting voice and blurry iconic face on the LP. She’s here and she still sounds fantastic, and still has that voice that can directly touch the soul.”

She’s looking to perform more. The only other thing that may be on her 2018 calendar is an appearance at Philadelphia’s Revolution Festival in October.

“I’d like to sing all over. I love singing in Europe, I hope people in Europe want me to come back. I love it,” says Waters, who considers herself a foodie and crazy about foreign films. “When I lived in New York, I went to Europe on my own and went to Montreal for a summer. I’d be happy if I could have a little tour of France and Italy, Spain and Germany. You can put the word out. I’m available.”

All you have to do is ask.

Nameless Sound presents Patty Waters with Burton Greene (piano), Barry Altschul (drums) and Mario Pavone (bass) at MECA, 1900 Kane Street at 8 p.m. Monday, April 9. Admission is “pay what you want”; folks 18 years old and under get in for free. For more information, see namelesssound.org and pattywaterssings.com.

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

Patty Waters Sings Again, Scheduled to Make Her Texas Debut

Courtesy of Nameless Sound

Patty Waters, in a rare interview with Houston Press, says that part of the reason why she didn’t perform for decades is because nobody was asking her to perform.

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]