By Kenneth Womack

576 pp.

$30

Chicago Review Press

With music biographies, it’s not common to see one about a record producer, even a well-known one. It’s even rarer to think about one sporting nearly 500 pages of text. And nearly shocking to know that book is the second volume detailing the life of said person!

But then again, not every producer is George Martin, who was both behind the studio glass and inside the floor with the Fab Four for the majority of their lifespan from untried beat group that (gasp!) wrote their own material to arguably the four best-known people on the planet – who were all under the age of 30!

As a producer, it’s general knowledge that Martin was far more than just a knob twiddler – he was practically a collaborator with the Beatles, especially as their music grew more sophisticated and required backing music and arrangement with strings, brass, and music that was more Mozart than Muddy Waters. And he helped Mssrs. Lennon, McCartney, and Harris turn their brilliant – but sometimes vague – ideas into the songs known and loved today.

Kenneth Womack has done some exhaustive research here, both on his own and utilizing other sources. He goes into great detail about Beatles’ recording sessions and Martin’s contributions to them.

Make no mistake – this is not for the casual fan. But the book is chock-full of anecdotes both somewhat familiar to diehards (Martin’s shrill string arrangement for “Eleanor Rigby” was inspired by Bernard Hermann’s music for the movie Psycho). And crazily specific (the jet airplane sound at the start of “Back in the USSR” comes from the EMI library sound effects reel “Vol. 17 – Jet and Piston Aeroplane”).

Readers also learn that David Mason’s piccolo trumpet solo in “Penny Lane” was done in one take, the exhausted musician feeling that he could do no better. And that Martin was shocked to discover that his young son could hear the whistle and the end of “A Day in the Life” that he and the Beatles thought only dogs could make out – not realizing that the hearing range of children is actually wider than adults.

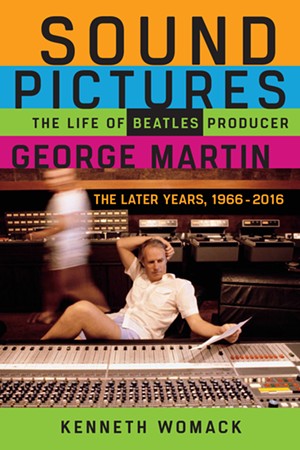

Sir George Martin and son Giles won two awards at the 2008 Grammys for the soundtrack to the Cirque de Soleil show "Love." Giles has become the custodian of the Beatles' musical legacy.

Photo by Alamy, Inc./Courtesy of Chicago Review Press

And even then, he was little more than a man-for-hire – earning a seemingly paltry 15 pound session fee for producing, arranging, and some writing on the orchestral parts of “All You Need is Love,” which few ears could fathom today being not part of the song.

Of course, it’s easy to 2018 quarterback the situation, given what has become of the Beatles music and legacy, something even the group themselves couldn’t imagine. In one early interview, Ringo Starr noted that when his musical career blew over in a couple of years, he would open a string of hairdressing salons!

Martin would work with other clients before, during, and after the Beatles: Gerry and the Pacemakers, Cilla Black, the Scaffold, Jeff Beck, America, Cheap Trick, and a solo Paul McCartney (many times) over the years. But in Mafia terms, his bones were made and his legacy and reputation wrapped around the 1960s work

Ultimately, the dapper, impeccably-dressed, and sonorous George Martin was a combination father figure, employee, ringmaster, and collaborator to the Beatles. Scholars of the group can (and do) debate endlessly just how much of George Martin’s own contributions are part of Beatles music, but Womack makes clear where he stands on the status of the true Fifth Beatle.

BONUS REVIEW!

Playing Changes: Jazz for the New Century

By Nate Chinen

288 pp.

$27.95

Pantheon

Of all genres of music, there is none whose perception and contemporary players are in as much competition with the pass as jazz. It’s also likely the biggest recipient of headlines like “Is Jazz Dead?” soon to be followed by “Jazz is Back!”

As a writer for the New York Times and Jazz Times, author Nate Chinen knows this, and in this perceptive book, strives to make peace with both entities.

“Jazz was enshrined in the popular imagination as a historical practice, a set of codes to be reenacted endlessly,” he writes. “Market forces – primed by a relentless campaign of reissues and compilations, tributes and emulations – had fed a common perception that the music had reached its peak in a distant golden age.”

Not so fast. Chinen argues that today’s top practitioners like Kamashi Washington, Esperanza Spaulding, Vijay Iyer, Steve Coleman, Joshua Redman, and the Houston-educated HSPVA pair of Robert Glasper and Jason Moran are not only pushing the music forward, but embracing others sounds like hip-hop, rap, and contemporary R&B into the party. And you don’t have to know the difference between bop, hard bop, and post-bop to appreciate it.

But the book is more than encyclopedia-like summations of these careers and records to date. Chinen has tied together stories and movements of the past like jazz fusion to show modern players, while part of a lineage, are not imitators. And also how jazz critics, college professors, and festival programmers can both aid and stint the book’s thesis, while interest in the music outside of the U.S. and Europe are also adding chapters to the jazz story.

Finally, Chinen gives a nod to jazz players who come from a certain familiar state and how they’ve changed the game. “Texas musicians have a different approach to playing. It’s not from a mechanical standpoint,” he quotes sax player Keith Anderson as opining. “The way we play is not based upon what we see on paper. It’s based on all feeling and listening.”