Over in Memphis at Stax Records, 1968 started off on a jarring note as musicians and executives were reeling from the loss of the label’s greatest star – Otis Redding – in a plane crash barely a month before. The accident also took the lives of four the six members of the rising band the Bar-Kays.

The R&B/Soul label suffered a massive setback in the year as well when, as part of a contract clause in their separation from distributor Atlantic Records, the Stax lost rights to all music recorded in their back catalog, including massive hits by Redding, Sam & Dave, Booker T. and the MG’s, Rufus & Carla Thomas, and more. The found a new financial backer in Paramount Pictures, but in terms of music, had to essentially start all over from scratch.

It’s why the new 5-disc box set Stax ’68: A Memphis Story (Craft Recordings) carries such importance, featuring every single A&B side released that year – 134 tunes in all – released under the Stax and subsidiary labels. It’s a breathtaking expanse of music featuring both the biggest names in soul and the acts mostly lost to history. And many tracks boldly mix the musical and the social together.

“What makes this [collection] different is that 1968 was such a historic period of all historic periods, and also in our existence at Stax Records. After we lost our catalog, we were considered dead by the industry, and we were,” says 78-year-old Al Bell, at the time Vice President of the label.

“But I couldn’t accept that. I believed we could turn it around, and we did. We had a vision. We rebuilt what was already built. That year was our turning point. I tell people what was before was the Old Testament, and we had started the New Testament.” Bell would later rise to become President of the label and a co-owner, leading Stax to a second great and more commercially successful era in the ‘70s before the entire operation went bankrupt (for more info, the two best resources are the books Soulsville U.S.A. by Rob Bowman and Respect Yourself by Robert Gordon).

But back to 1968. MLK’s assassination at the Lorraine Motel was a mere 2.5 miles from Stax headquarters and studio at 926 E. McLemore Ave. And the same racism that Dr. King tried to combat was felt daily at Stax and its surrounding environs.

Former Stax President/Co-owner Al Bell at the former studios and offices of the label, now home to the Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis.

Photo courtesy of Reed Bunzel

“There was so much racism in Memphis at that point. I had not experienced it in other cities like I did there. But for those of us who worked at Stax, white and black, we were together,” Bell recalls. “That came from the [white Stax founders/owners], Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, who didn’t have a racist bone in their bodies. They weren’t looking at color when you walked through the door, they were looking for talent. And that made Stax a symbol of hope for the future.”

Still, Bell recalls many in the city were not thrilled with the race mixing going on inside the offices and recording studio. He recalls walking on the street outside the building with Stewart and another white business executive when a police car pulled roared up and two officers jumped out, telling them to get back inside because “we don’t allow niggers on the street with white folk in Memphis.”

Conversely, as the Black Power movement ramped up, Memphis activists wanted Stax to purge the label of any white influence or artists. That meant guitarist Steve Cropper and bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn had to be escorted to their cars by Bell and a couple of pistol-packing bodyguards. It was extra ironic, considering that Cropper and Dunn were the white half of the group Booker T. and the MG’s, who served as the Stax house band as well as having a very successful career on their own (the “MG” even stood for “mixed group”).

Stax ’68 also contains a booklet with a long form essay about Memphis at the time, extensive liner notes on the music, and a lot of rare photos. What makes the box set democratic in nature is that the labels biggest star’s (Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, the Staple Singers, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Johnnie Taylor, Eddie Floyd) share disc space with acts known only to music nerds (Ollie & the Nightingales, Jimmy Hughes, Judy Clay, Harvey

Scales and the Seven Sounds, The Mad Lads).

Steve Cropper's distinctive guitar was heard on many Stax hits that he also helped co-write or produce. But he still had to be escorted to his car after work due to racial tensions in Memphis in 1968.

From the Don Nix Collecton/Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Bell says he hopes this project will boost the profile of two acts in particular: Linda Lyndell and the Soul Children. Lyndell’s “What a Man” was not a hit when released under her name, but served as inspiration – with the title hook line repeated – for the smash 1994 collaboration between Salt-n-Pepa and En Vogue, “Whatta Man.”

“Linda in particular, that song should have been one of the biggest records in America at the time, but it didn’t get the exposure.” Bell says. That Lyndell was white and many black radio stations refused to play the record because of that threw the race card again into the argument. “And I especially liked the Soul Children. They had four lead singers and such great music. But we couldn’t get them positioned in the marketplace like they deserved.”

It’s no accident that the box set has the subtitle “A Memphis Story” in the title, because the arc of the label and what was happening in the city at the time were intertwined. There is a lot of joy in the music, and much of it is about the triumphs and tragedies of romance, while others had that infectious groove made for the dance floor.

But the line was blurred between society, politics, and the music, whether in how the business operated or in songs like The Staple Singers’ “Long Walk to D.C.,” or Shirley Walton’s “Send Peace and Harmony Home.” The lyrics that Bell wrote for the latter originated as a tribute to the then-living Dr. King, but became an elegy when it was released after his death. Shot dead at the same motel that black and white Stax artists would often gather to write music together at.

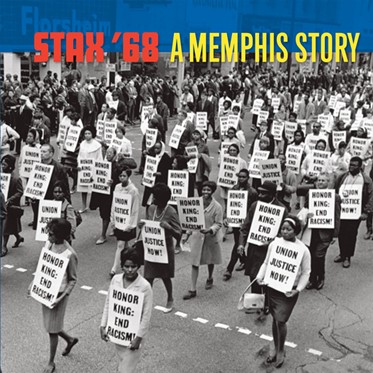

And if there's any doubt about intentions, the cover of Stax '68 features not a studio or stage shot of one of the artists, but scores of black protesters marching in the streets and bearing signs that say "Honor King: End Racism" and "Union Justice Now!" Inside, there's a shot from the sanitation workers' strike with protesters each holding other signs with a simple declaration: I Am a Man.

“It’s impossible to separate the politics from the music, but the songwriting and recording were African-American music, so it was going to [address] things like that,” Bell sums up. “You were hearing in the music what was going on in our lives at the time.”