I spent a lot of this past Wednesday choking back tears over a robot, and judging by social media I am not alone. NASA announced that they were declaring the Opportunity rover on Mars “dead.” After more than a decade patrolling the surface of our nearest neighboring planet and contributing an incredible amount of scientific understanding, the robot nicknamed Oppy was caught in a terrible sandstorm last June which buried its solar panels. The final message we received from Oppy was basically “Mars is getting dark and my battery is low.” For eight months NASA tried to reestablish contact with the rover, but finally gave up. Their last, desperate wake-up attempt before declaring its mission over was the song “I’ll be Seeing You” by Billie Holliday.

I’m not kidding when I say I spent hours after hearing the news feeling terribly depressed and a pretty close approximation of physical grief. The tributes to Oppy got weirdly personal and deeply heartfelt. The Onion of all places ran a spoof obituary that used comedy to convey the emotion of the situation perfectly. XKCD put a hopeful spin on the situation with look at all the images the rover left us. If this Seebangnow comic about death greeting Oppy doesn’t hit you right in the soul then you might not have one. Plus, I’m certain it’s only a matter of time until one of Doctor Who fan art people has a drawing of Jodie Whittaker rescuing the bot, and when that happens I plan to take to my bed for the rest of the day.

The question is, why? Why does this hurt me? Opportunity didn’t have feelings. It faked its enthusiasm for scientific discovery and appreciation for the beauty of the universe because we programmed it to do so. I didn’t lose a friend, but it feels like I did.

It’s been recognized for a while now that humans are starting to develop new relationships with their technology that borders on treating them like living beings. Consider Roombas, the robotic vacuum cleaners. One study of thirty users showed that people often begin treating Roombas like pets, including rushing to help them out of corners and making changes to floor coverings so they don’t tangle the bot. One man in the study said he would even introduce the robot to people, and I remember reading somewhere about a person whose Roomba stopped working during rain storms so he began petting it as if it were scared.

Or take me with Siri. I don’t use her very often, but when I do I always say thank you when I’m done. So do lots of other people. These creations don’t care about how we feel about them, but we do it anyway.

I asked Rebecca Gibson PhD, Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Notre Dame and author of the upcoming book Desire in the Age of Robots and AI: Investigations in Science Fiction and Fact from Palgrave Macmillan, why I was so down about a machine like Oppy.

“We anthropomorphize it for a whole host of different reasons, but I think that it's more impactful because it is so far away and so alone,” she says. “We might all swear at and thump our electronics if they're malfunctioning, treating them as though they would be able to respond and correct themselves, but there's very little personal impact because we're much more aware of their impersonal/non-human natures. Opportunity affected us so deeply particularly due to its last transmission, in effect, its last words. They were very human, and made us feel our own mortality.

“Robots, being things humans have created, take on aspects of humanity in our minds. You didn’t personally create this one, but you watched as it was built, tested, deployed. You, we all, experienced its first halting steps on a new world, heard it tell us all about its day, saw its missteps and triumphs. In our collective consciousness, we just watched our interplanetary child die.”

It’s hard to argue that Oppy meant something bigger than most individual humans. I used to joke that the United States now controlled all the water on Mars thanks to our robot army, but behind that snarky rejoinder was a feeling that something out there was doing spectacular work on our behalf. It was hard not to feel overwhelmed with emotion when Oppy sent us the sunrise from the Martian surface, or to empathize with the NASA scientists who prayed and hoped for their wondrous invention to keep on going in spite of the odds.

The only dark side to me is what it means for use to feel like this for things we essentially treat as slaves. The ethics of sex bots is already under consideration as they become more and more responsive to their owners, and any trip to a Men's Rights forum will show in graphic detail how gleeful some people are about the prospect of being able to own a woman who can't say no. In an article with Quartz, Ilya Eckstein, CEO of Robin Labs, stated that around five percent of interactions with the bot Cortana were sexually explicit inquiries about it. We’re sexually harassing AIs just because we can and that’s not encouraging.

I think we ought to take this moment of loving Opportunity to consider what the future might look like between us and artificial beings. How are we going to treat them, considering our history with our own species? It’s going to matter as they evolve and our dependence on them grows.

“The original creation, Frankenstein’s creature, certainly hated his creator and the ignorance, cruelty, and fear with which he was treated,” says Gibson. “That novel, which was many things, was a warning against imbuing our creations with consciousness, strength, and a sense of purpose and turning them loose, but it was more about our own lack of moral and ethical compasses. I don't think it's good to treat things we make, that have consciousness, as slaves. But I do think we are going to do so, because we feel that we retain certain rights over things we have made.”

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

Why Are We So Heartbroken Over a Dead Robot?

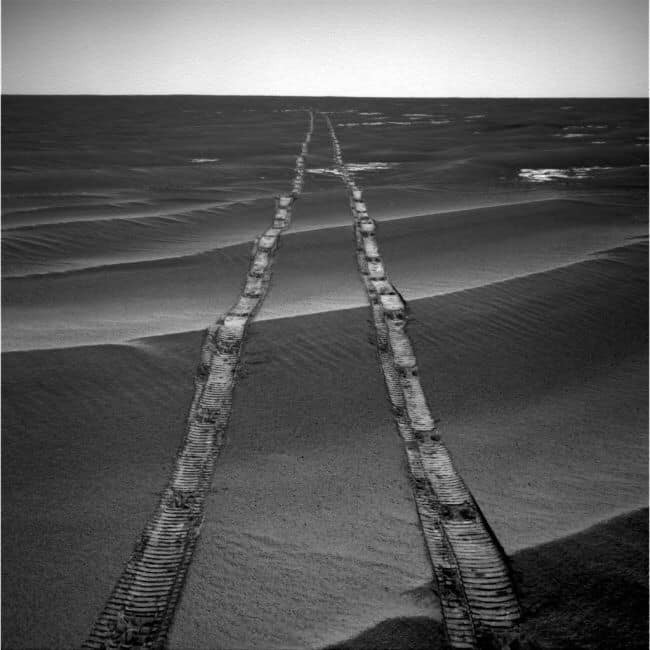

Photo by NASA.gov

"Walk any path in Destiny's Garden, and you will be forced to choose, not once but many times. The paths fork and divide. With each step you take through Destiny's Garden, you make a choice; and every choice determines future paths. However, at the end of a lifetime of walking you might look back, and see only one path stretching out behind you; or look ahead, and see only darkness."

-Neil Gaiman

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]