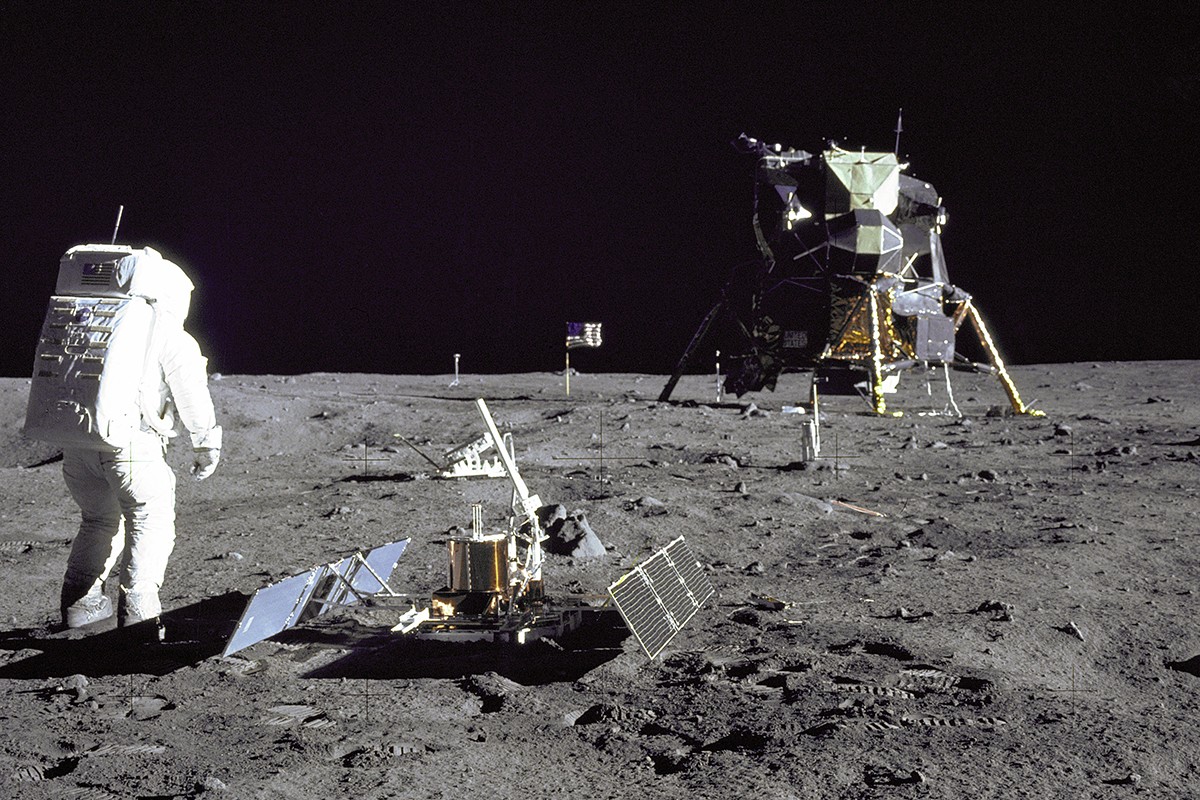

And so it went for President John F. Kennedy's 1961 declaration that we would send an American safely to the moon before the end of the decade. Yes, mission accomplished, but it's only with 20/20 hindsight that we know the cost.

"For every hour of space flight it required a million hours of work back on Earth," says Charles Fishman, a journalist, space reporter for The Washington Post, and The New York Times bestselling author. Fishman explores those efforts in his new book, One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon, published by Simon & Schuster.

"It was impossible when Kennedy said 'Let’s do it.' We did not have the tools or the technology. The people at NASA thought at the time, and they told President Kennedy at the time, that they thought it was 50-50 chance to get people to the moon, return them safely, and do it by the end of the decade," says Fishman.

One Giant Leap looks at the 400,000 people who worked to make the 2,500 hours of Apollo space flight possible: including 11 Apollo missions that went to or landed on the moon, as well as two that stayed in Earth's orbit.

Charles Fishman is a three-time winner of the Gerald Loeb Award.

(L) Book jacket artwork courtesy of Simon & Schuster and (R) photo by Lidia Gjorjievska

One of those unsung heroes was Houstonian Bill Tindall, a senior NASA official at the Manned Spacecraft Center who was responsible for plotting out second by second what needed to happen at Mission Control, on the moon, in the computers and on the spacecraft.

1. Tindall was a math genius, a whiz at orbital mechanics, and so he was sent to MIT in 1966 to help them edit and simplify computer programming that was so bogged down with code it wouldn't fit on the computers.

2. Not only did Tindall have the technological prowess to gain the respect of the programmers at MIT, he had a funny, self-effacing personality that made them receptive to his suggestions and changes.

3. He felt that the astronauts had too much work to do, and was constantly looking for ways to eliminate extra tasks or keystrokes.

4. He anticipated the possibility of using the lunar module as a lifeboat — long before Apollo 13 — and created a reference listing of all the research in case a problem developed.

5. Tindall began writing daily memos that succinctly captured the critical elements of long and complicated meetings to let the astronauts, NASA, MIT, and Grumman (making the lunar module) know exactly what needed to be tackled next.

"So these memos were blunt and funny and sometimes kind of brutal but he wrote 1,100 of them. He wrote them for years, two or three a week," says Fishman. "They were going to 40 or 60 or 150 people depending on the memo, and they reported how things were going, what the problems are, who wants to help, who wants to hold up their hand.

"What you’ll discover is that they turned out to be a brilliant management tool because everybody started looking forward to them. He had an incredible knack for summarizing daylong meetings or even meetings that lasted two days," says Fishman.

"People started looking forward to the Tindallgrams; not because they were amusing, this was how to learn what the state of things was, what needed attention. As the moon landings were getting closer and closer, the Tindallgrams had a sense of immediacy and urgency," says Fishman, who shared a link to some of those archived memos.

"Apollo wouldn’t have gotten to the moon without Bill Tindall. What MIT would have told you is they were contemptuous and dismissive in the beginning, then they thought he rescued them from disaster," says Fishman. "When I went back to talk to those folks the feeling was, 'They could have sent somebody with a different personality who made the exact same decisions, and it would have been a disaster.'" Tindall was the perfect person at the right time to make the impossible possible.

Fishman's book also looks at how Houstonian Jack Kinsler drew the preliminary sketch for the lunar flag assembly, with a second horizontal bar to make the flag look like it was flying in airless space. Other unsung heroes include workers who sewed the spacesuits and parachutes by hand, who used caulk guns to apply the space shield to the back of the command module one beehive cell at a time, and those who programmed code with needles and wire.

"The folks at MIT created a computer in 1969 that was the smallest, fastest, most nimble computer that had ever been created, and that computer was run by the astronauts themselves using their fingers on a keyboard at a time when virtually every computer in the world you had to submit punch cards or computer tapes.

"That computer was so far in advance of the technology that was available that the software had to be woven by these women in Waltham, Massachusetts, former textile workers in a factory that belonged to Raytheon. The software was literally woven by hand with needles, using wire instead of thread, using ones and zeroes. It took eight weeks to weave the programming for a single Apollo flight computer," says Fishman.

Author Charles Fishman found himself over the Gulf of Mexico in G-Force One, a Boeing 727 owned by Zero Gravity Corporation.

Photo by Bob Croslin

In anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing on July 20, Fishman has embarked on a 50 stories in 50 days project for FastCompany.com where he rolls out one space geek tidbit a day. And he'll be in Houston on June 17 for a book signing for One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon.

The book signing is scheduled for June 17 at 7 p.m. Monday at Brazos Bookstore, 2421 Bissonnet. For information, call 713-523-0701 or visit brazosbookstore.com. Book price is $29.99.