“I’m in bad shape, brother.” These were the words Eugene Farooq says he heard from his long-time friend, co-worker and mentor, Akbar Shabazz, who could barely get out a breath. Days later on April 23, despite being hospitalized, Shabazz would lose his battle against the infectious coronavirus.

In September 1977, Shabazz became the first Muslim chaplain employed with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, first beginning as a volunteer before joining the agency as a Regional Area Muslim Chaplain in a career that stretched over 40 years.

According to the TDCJ, the 70-year-old Shabazz first started feeling ill with symptoms of COVID-19 on April 3. He was taken to Methodist Hospital in The Woodlands where despite a nearly three week-long fight against COVID-19, Shabazz died in the early morning hours. His passing came as a significant blow to the TDCJ.

“Chaplain Shabazz was a part of the foundation of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice,” TDCJ Executive Director Bryan Collier said. “His dedication to his faith, his family, and this agency will not ever be forgotten. I considered him a personal friend and this loss to all is heavy. We can only hope that the thoughts and prayers of the TDCJ family help to lighten the burden.”

At the same time, Shabazz’s loss means even more to Texas Muslims. To them, Shabazz was not seen as a chaplain but as an imam, a religious leader in Islam. And since his death fell on the first day of Ramadan fasting, many Muslims like Eugene Farooq looked forward to their first meal of the evening but the news about Shabazz’s passing made it difficult to appreciate it.

“It’s a great loss for the community because Imam Shabazz had touched a lot of lives of believers not just those in prison but outside because he was very well-liked, so it’s going to be something getting used to,” Farooq explained. “Not hearing his voice, [for example]. Allah knows best, but I know it’ll be something different from the prison unit because he was like a landmark.”

A retired Muslim chaplain, Farooq noted it was Shabazz who brought him on board with the TDCJ where he worked for 25 years. According to Farooq, the two became acquainted after Shabazz relocated from Huntsville to Houston, where he spent most of his time as a prison chaplain. However, the two were more close friends than co-workers, Farooq explained.

“We would travel together on many occasions going to the different prisons, but we were fishing partners and would also fish all the time,” Farooq said. “I would go to Huntsville and we would go to different hideaways he discovered while he was working there and spent quite a lot of time together.” Their shared friendship continued for several years and they were able to speak by phone once Shabazz was hospitalized.

“I think he had been there one day,” Farooq said. “And I mean, the conversation it was really a heart-felt conversation. It really saddened me because his words were, ‘I’m in bad shape brother. I’m in real bad shape.’ And he wanted to continue the conversation but I tried to finish up because I saw he couldn’t hardly breathe and I told him, ‘Look, you need to save that energy so you can breathe because the longer we pull onto this conversation, the more difficulties you’re going to have.’ And he understood, but he still didn’t want to get off the phone…And the last thing I remember him telling me, was ‘Brother, I’m in bad shape.’”

That phone call wound up being their last conversation. When he heard the news of Shabazz’s passing, Farooq says: “I was really touched emotionally. I’ve lost two brothers in recent years my younger and older brother. I had almost the exact same feeling when I lost my blood brothers.”

Muslims like Jihad Muhammad, 52, a resident imam for the Fifth Ward Islamic Center for Human Development, mirrored Farooq’s statements on Shabazz. Muhammad said he first knew Shabazz when he was incarcerated but shared extensive conversations with him after he was released several years ago. Instead of an authority figure, Shabazz was seen by people as more of a benevolent educator because of how amicable he was, Muhammad said.

“He was very approachable, accessible and very humble,” Muhammad said. “I admired the way he carried himself in a very unassuming way. If you didn’t know him or his history, it’s not something you would assume.”

Shabazz often went above and beyond in setting accommodations for incarcerated Muslims trying to change, with respect to Islamic rites and regulations established by the TDCJ.

“He had his hands in administrative decisions because he was the main person,” Muhammad said. “When it came to Ramadan, for example, the secular institution would not bother to make accommodations for Muslims. He was our inside guy who looked out for us that had no one to look after them.”

When word came of Shabazz’s death, Muhammad said a surreal feeling overcame him. He had thought of Shabazz as a seemingly untouchable, albeit silent, force when it came to being a Muslim community leader and mentor.

“Shabazz’s death was just a sense of ‘we lost a great one’ and there’s huge shoes to fill because the work still has to be done,” Muhammad said. “He was such a giant who always expected him to be there, manning the wall, always in the chair. We just assumed it would last forever and so it’s a very sobering thought to know he is gone.”

Another retired Muslim Chaplain, Haywood Talib, 80, shared similar sentiments about Shabazz’s work in the prison sector and noted how he was essentially the arbitrator for any accommodations.

“[His death is] a big shock but the bigger shock is in the prison, because he was such a stabilizing force for everybody including the staff, directors, and all that but at the same time, whoever had a question or a concern, they was looking for Shabazz and we would always direct them to him to, ‘make sure you talk to Shabazz, make sure you run that by Shabazz.’ He was hands-on all the time and they’re going to miss him without a doubt.”

When it comes to Islamic chaplains in Texas, Talib mentioned their work is crucial but due to the scarce number, often he and others would oversee several prison units across the state.

“I was mainly in charge in Abilene, but my area of work spread as far up as Daleheart, Texas,” Talib explained. “I had about 16 or 17 units that I was responsible for but there was only four of us (including Shabazz) and we were assigned to work all of Texas.”

Despite their heavy workload, reformed Muslims like Jihad Muhammad still express gratitude for the work of folks like Shabazz because of how vital it is, especially for offenders.

“It’s priceless. You can attach no value to it,” Muhammad said.

Simultaneously, Muhammad concluded by saying Muslim chaplains and imams like Shabazz are not always given the credit they deserve, but work tirelessly nonetheless.

“You have a handful of chaplains that are serving hundreds of units, state jails, prisons; their workload is something to behold but they still get there when they can, coordinate volunteers for us,” he said. “Imagine if you will many young men, especially African American going inside this prison system uncivilized and savage in many ways, not really knowing how to live in a communal setting, you know? And having to be basically molded by the Qur’an, by the life of [the Prophet] Muhammad, by men who are experienced in training; these men are giants in the lives of many Muslims.”

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

Friends and Co-workers Remember Texas’ First Muslim TDCJ Chaplain who passed away from COVID-19

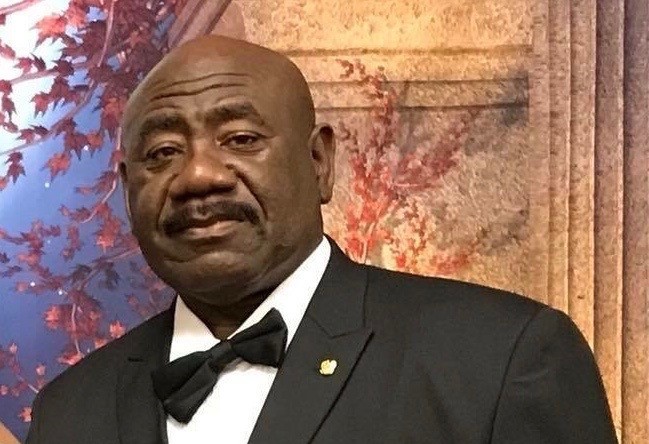

Photo by Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Chaplain Akbar Shabazz

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]