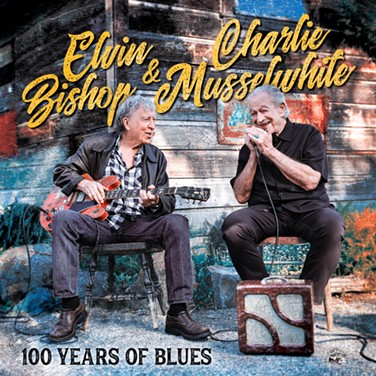

One of the tenets of blues music – especially that of the ‘50s/‘60s Chicago-based strain – is raw honesty. But it seems more than a bit dishonest that the title of Elvin Bishop and Charlie Musselwhite’s new record is 100 Years of Blues (Alligator). It’s supposed to represent how long they’ve been honing their craft, but a more accurate (if not as poetic) title would be 110 Years of Blues. Or even 115 Years of Blues.

Given their long history and friendship, it’s surprising that this is the first time the pair have done a full collaborative album. The idea stemmed from a recent tour they did together, playing music and swapping stories. It was a big hit with audiences, who seemed to have as much fun as the performers did. “We figured it would be something we could sell at the shows. But now we can’t do shows anymore!” Musselwhite says.

The pair both moved to Chicago in the early ‘60s – singer/guitarist Bishop from Oklahoma, and singer/harmonica player Musselwhite from Tennessee. They first met “in 1962 or 1963” perhaps at a club. Bishop was also hanging around bluesman Big Joe Williams, who lived in the basement of the city’s famous Jazz Record Market. So did Musselwhite, who worked there. “There were a lot of cots in that basement!” Musselwhite recalls.

But when Musselwhite got into a fistfight with owner Bob Koester, he and Williams were forced to move into... another record store, the Old Wells Record Shop. Though this time, they had actual beds in a hallway room.

Bishop and Musselwhite both found work while gigging informally and scheduled at many of the very active blues clubs that dotted the city’s south and west sides, many within walking distance of each other. It seems like almost a mythical, fantasy time where you could see so many shows within walking distance of each other. And for cheap.

“Blues in Chicago was the number one thing happening, and everybody was so good, and all in one place. These clubs were open from nine at night to four in the morning, and to five on Saturdays. Then there were the Blue Monday parties. You could see Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Little Walter for two bucks!” the garrulous Bishop notes.

“Sometimes it was even cheaper!” Musselwhite adds. “You could get into Pepper’s on a Monday or Tuesday night for 50 cents, and you got a ticket for a free beer. These guys were players, and the level of musicianship was high. They weren’t playing sloppy jams.”

More importantly, the young men found acceptance and tutelage from many of blues’ biggest names who could fill large venues overseas, but still gigged at small Windy City clubs like Pepper’s, Silvio’s, and the Checkerboard Lounge. And if Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Magic Sam, and Little Walter gave these young white boys their stamp of approval, who was going to question that?

“They were way nicer than they needed to be to us, and it was a beautiful thing. I don’t know how much mentoring there was, though. You were pretty much on your own musically,” says Bishop. He remembers going over to guitarist Otis Rush’s house to work on some licks, but not before the elder bluesman would go to the kitchen cabinet, pull down a pint of Old Granddad whiskey, and pour shots for the both of them.

“And those long club hours worked well for those trying to get started,” Bishop continues. “I don’t how big of a star you are. When it gets to one, two, or three o’clock in the morning, you were glad to see any help come through the door! And every time you went to sit in, it was sort of an audition. That’s what motivated you to learn everyone’s tunes. Nobody was making a whole lot of money.”

Musselwhite adds that the older blues players were often flattered that young white boys not only came to see them, but knew all about them and their music. They had done their homework.

“Blues was considered old folks’ music to kids like us. They weren’t into that. There was nobody our age in those clubs – it was strictly adults!” he says. What irony that a few years down the road, the blues filtered by rock in acts like Cream and Led Zeppelin would prove so hugely successful with young audiences.

Some of those venues and blues men are name checked in the title track, which Bishop and Musselwhite originally recorded a different version of years ago. The record 100 Years of Blues features nine originals and three covers, with both men featured on lead vocals. They include chugging numbers (“Birds of a Feather,” “Blues, Why Do You Worry Me?” “If I Should Have Bad Luck”), slower, heart-rending fare (“West Helena Blues,” “Good Times,” “Midnight Hour Blues”) and an instrumental (“South Side Slide”).

But the two tracks which speak to more contemporary topics couldn’t be more different. On the rollicking “Old School,” Bishop sings how proudly Luddite he is in today’s tech-driven society: Don’t fool with no Facebook/No Twitters and tweets/Call me on the phone if you want to talk to me! He also makes, uh, other needs known: Don’t send me no Email/Send me a FEmale!

But on the first single “What the Hell?” the target is not a wayward woman, demanding boss, or two-faced buddy. It’s the guy in the Oval Office. He’s the President/But wants to be the King/Know what I like about the guy?/Not a goddamn thing/I wanna know/How can four years be so long?/Lord have mercy/What the hell is going on?

Bishop originally wrote the music for a song with completely different lyrics in the aftermath of September 11 and titled “What the Hell is Going On.” But he revamped the words to address a more current situation.

Musselwhite is on another new record as part of the roots supergroup the New Moon Jelly Roll Freedom Rockers along with Alvin Youngblood Hart, Jimbo Mathus (Squirrel Nut Zippers), and Jim Dickinson with sons Luther and Cody (North Mississippi All-Stars). Their casual, ad hoc recording session recorded in 2007 has just been released as Vol. 1. “I didn’t know if anybody was ever going to put that out. It was done such a long time ago!” he says.

Bishop is also a member of a special club. In 2015, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as part of the groundbreaking Paul Butterfield Blues Band. The biracial group was perhaps the perfect synthesis of melding classic Chicago blues style with a then more modern rock/electric sensibility.

“I was surprised they put the Butterfield Band in there at all. Everybody else in there sold millions of records. We probably sold fewer than anybody! It was probably because other musicians liked us,” he says. Though Bishop’s biggest memory of the evening had nothing to do with accolades, statutes, or rubbing elbows with other music royalty.

“I had a real rough time at that ceremony,” he recalls. “On the way to the airport in San Francisco, I threw my wife’s suitcase in the back of my father-in-law’s truck. And when we got there, her suitcase was gone. I guess I didn’t close the back of the truck!” he says. “You can imagine a woman going to an event like that without her good clothes. So yeah, I was pretty stressed out!”

“Time to go shopping! Musselwhite adds.

When asked what each one of them brought to the new record nobody else could, the 77-year-old Elvin Bishop and 76-year-old Charlie Musselwhite turn into Fan Club Presidents for each other.

“Well, I called Charlie up a few years ago to give him a pat on the back because he’s one of the few guys our age still out there doing it and proving himself. He ain’t just living off the past like a lot of guys are,” Bishop says. “He’s so solid, and it’s a great joy to play with a harmonica player who isn’t just recycling Little Walter licks!”

“First of all, Elvin writes great tunes. He really delivers them with a message,” Musselwhite counters. “He’s a joy to be around and a great guitar player. And we have such similar tastes and knew a lot of the same musicians. It’s just effortless to play with each other. We’re kindred souls.”

Finally, as to what they’re doing during the pandemic when they can’t tour, Musselwhite has been doing house chores he’s been putting off, preparing for a hip operation, and planning to move into a new house with wife/manager Henrietta. Both men have also been working on their green thumbs. And sleeping.

“This is the first regular sleep schedule I’ve had in fiftysomething years! No more getting up at 3 o’clock in the morning to get to the east coast!” Bishop laughs. “I also have a garden and a wife. And if those don’t keep you busy, nothing will!”

For more information, visit ElvinBishopMusic.com or CharlieMusselwhite.com

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

Elvin Bishop and Charlie Musselwhite on a Century (or More) of Chicago Blues

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]