By any measure, 2020 has been one of the worst years of all time. It’d still rank high on the list of most awful years if it were only for the still raging coronavirus pandemic that’s killed over a million people globally and the plethora of natural disasters that have swept deadly fire and raging flood waters across the country.

But on top of all that, this year has laid bare the tragic state of racial inequality in America. COVID-19 has disproportionately killed and stolen the livelihoods of minorities, and the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd have made it clearer than ever that American law enforcement must be held more accountable for devaluing Black life.

“2020 has been the year of Jumanji, and every time somebody rolls the dice, there’s a fire tornado, another officer-involved shooting and 64 hurricanes at the same time in the Atlantic and Gulf,” said Ashton Woods, founder of Black Lives Matter Houston. “We’re just working through what we have to work with, but again, the reality is that our work never stops.”

Woods, a New Orleans native who moved to Houston in 2005, said that watching the inept government response to Hurricane Katrina is what lit the fire in him to devote his life to social justice.

“The best way to put it was I was watching my hometown drown, predominantly Black, and saw the government not give a shit,” he said.

Almost a decade later, that hunger to fight for the dignity of his fellow Black Americans was what led him to the streets of Ferguson and St. Louis, Missouri in the summer of 2014 to protest the police killing of Michael Brown.

The Black Lives Matter movement had sprung up a year prior after Trayvon Martin’s killing in Florida, and the furor over Brown’s death took the movement to the next level. Woods decided to start a Texas chapter of Black Lives Matter during those protests, which eventually morphed into Black Lives Matter Houston.

After Floyd’s death under the knee of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin back in May, the national spotlight turned to Houston, his hometown. In early June, tearful politicians and celebrities flocked to the city for Floyd’s memorial service, and Woods helped organize a massive 60,000 person march through downtown to honor Floyd’s life and demand reforms to address the police brutality that has taken far too many Black men and women’s lives.

No BLM Houston events have come close to that scale since, but that doesn’t mean the local social justice group hasn’t been putting in work to create a more equitable Bayou City and to support the needs of Black Houstonians.

Brandon Mack is a Black Lives Matter Houston organizer who also works in Rice's admissions department.

Photo by Schaefer Edwards

He explained that in recent months, BLM Houston has used donations to its mutual aid fund to help pay for gift cards for groceries and other supplies to Black families struggling due to COVID-19, and has raised money to pay for school supplies donations to support Houston Independent School District students in need. BLM Houston has also rallied its supporters to contact local Justices of the Peace to demand that they halt eviction cases due to the city’s refusal to support an eviction moratorium during the pandemic.

Mack’s path to Black Lives Matter Houston started during his childhood in Lake Jackson an hour south of Houston. In high school, the discomfort Mack experienced as one of the only Black kids in his predominantly white high school helped him realize how unequal the playing field is for Black people in America. When Mack isn’t organizing with BLM Houston, he works as an Associate Director of Admissions at Rice University, and is a board member for both the Houston GLBT Political Caucus and the Mayor’s LGBTQ+ Advisory Board.

BLM Houston is able to quickly mobilize to support Black Houstonians thanks in part to its flat, non-hierarchical organization structure, which is similar to the way most BLM chapters across the country operate. That means all of BLM Houston’s five primary organizers all have an equal say in setting the group’s priorities, and that Woods doesn’t sit on an institutional pedestal with extra clout just because he’s the founder.

“We’re a team-based chapter. It allows for us to move faster in a non-traditional sense,” Woods said. “A lot of us had already been kind of disheartened and kind of turned off by legacy organizations like NAACP Houston chapter… We don’t believe in trying to wait for 150 people to say yes or no on whether to move on issues.”

“Because of the fact that we operate on a flat level, literally you can contact any of us. We’re empowered to go ahead and move and do mobilization rapidly,” Mack said.

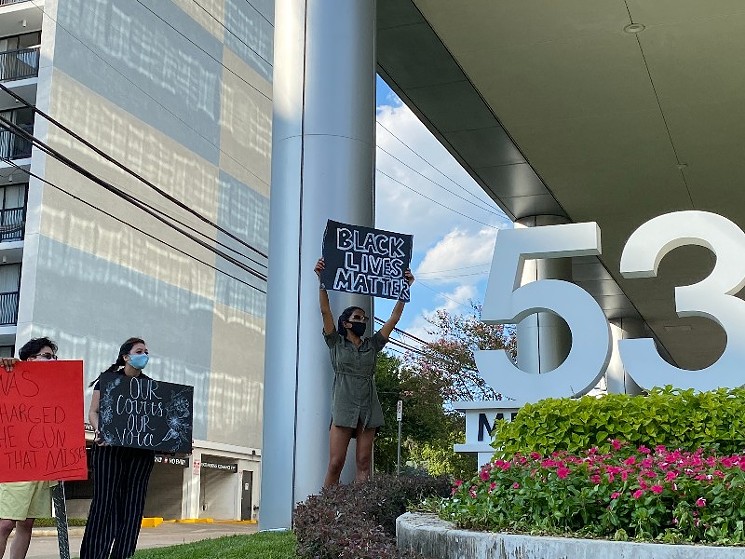

Black Lives Matter protestors gathered outside of Sen. John Cornyn's office September 26.

Photo by Schaefer Edwards

Woods and Mack are both gay Black men, and their fellow BLM Houston organizer Kandice Webber is a Black lesbian. “None of us are ever in isolation,” Mack said. “Our race is inherently important, as is our sexual orientation as is our gender identity, because we live these full lives where all of the different elements of ourselves are important.”

The issue of violence against Black women is front-and-center for BLM Houston thanks to last week’s news that the only criminal charge made against the Louisville, Kentucky police officers who shot and killed Brenna Taylor was for “wanton endangerment” on account of bullets that flew into the apartment of Taylor’s neighbor.

“Basically, they sent a message that we as Black people can be asleep in our beds, be murdered, and that’s perfectly fine. I wasn’t surprised, but extremely disappointed,” Mack said.

That deep disappointment over the Breonna Taylor case was shared by the nearly 80 Houstonians who took part in last week’s Saturday afternoon protest sponsored by BLM Houston and other progressive advocacy groups — March For Our Lives, FIEL Houston, Houston Indivisible and the Texas Organizing Project — in front of Republican U.S. Senator John Cornyn’s office on Memorial Drive.

“It’s a travesty. I think that our justice system needs to be reformed, because according to the law, everything they did was fine, but clearly, something’s not right. Justice isn’t being served” said protester Sophia Malik. “I just want everybody to know who’s suffering that they are not alone.”

For Woods, the lack of charges against Taylor’s killers drove home the importance of his criminal justice reform advocacy work. BLM Houston takes up most of his time these days, primarily through lobbying local leaders and state legislators to consider substantive policing policy changes. When he’s not organizing, Woods takes on paid speaker gigs about social justice and works as a political consultant.

He’s disheartened that Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner — whose campaign Woods worked on as an outreach director back in 2015 — hasn’t taken a more aggressive approach to local police reform.

“It was really personal for me at a certain point when I realized I’m really going to have to hold this man’s feet to the fire in a way I was hoping I didn’t have to,” he said.

When Austin's City Council recently voted to reduce its police department budget to fund non-police initiatives like mental health and violence prevention programs, Woods couldn't believe that Houston's City Council voted to increase HPD's budget earlier this summer. "What does that look like when you have to watch Austin, that has a majority white City Council, defund their police department when we have a majority people of color City Council who won't do a damn thing?" he said.

Woods doesn’t think Turner’s recently announced cite-and-release program to issue tickets instead of arrests for low-level misdemeanors goes nearly far enough. He also criticized Turner’s decision earlier this summer to create the task force on policing reform that released its recommendations this past Wednesday as a sign of “intellectual laziness” from the mayor.

“It’s time to peel the fucking scab back and rip the stitches out, and expose this shit so we can deal with it. And you know, that’s really what my work is,” Woods said.

That work continues. Woods said he plans to keep pushing local officials to take a more courageous stance on police reform, and Mack told the Houston Press that BLM Houston is already planning an event to commemorate the six-month anniversary of Floyd’s killing this November.

“We had over 60,000 people come out to the rally that was held in front of City Hall...where are they still at? If they truly are still dedicated to this, we should see them in six months,” Mack said.