The Lone Star State’s coronavirus response has been a lopsided battle between Gov. Greg Abbott — who’s wielded his executive powers to issue a statewide mask mandate and business restrictions — and local officials like Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner and Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, who were blocked by the governor’s orders from putting tougher COVID restrictions in place.

But thanks to the fact that the Texas Legislature only meets in odd-numbered years, and because Abbott’s executive authority meant he didn’t have to summon the Texas House and Senate to Austin for a special session, Texas legislators were powerless to shape the state’s coronavirus response for most of the pandemic.

To make sure they don’t get ignored the next time a deadly disease is floating through the state, both the Texas Senate and House have been debating new laws that would tilt that balance of power during a future pandemic much further toward the Legislature, adding new checks to the governor’s executive powers and further limiting the ability of local officials to shape disaster response in their own communities.

Right-wingers like state GOP Chair Allen West and state Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller have lambasted Abbott for putting far too many of what they regard as freedom-killing pandemic rules into place, including his mask mandate and business restrictions.

Abbott’s also been blasted by state Democrats for doing too little to respond to the pandemic, and for loosening virus-minded regulations too quickly in the face of pressure from his party’s rightmost flank despite the opposition of health experts.

In Houston, Turner and Hidalgo have been some of Abbott’s biggest critics, and have for months chastised the governor for blocking their ability to issue stricter mask rules and business occupancy limits they believed would have saved lives. But if the Legislature has its way, future mayors and county judges would have even less power than the puny authority granted to Turner and Hidalgo now.

The powers of the Texas governor used to be considered pretty weak compared to those of chief executives in other states, and even to those of Texas' lieutenant governor, who can bend the entire Legislature to his or her will by controlling the state Senate's agenda as Dan Patrick has skillfully demonstrated.

But through his handling of the state pandemic response, Abbott capitalized on the slow but steady accumulation of power within the governor's office over the past two decades, a trend that began back when former Gov. Rick Perry started filling state regulatory agencies with his hand-picked ideological allies. Abbott followed Perry's lead with a 2018 power move to require state executive branch agencies to funnel any proposed rule changes through the Governor's Mansion.

Abbott's choice to capitalize on the coronavirus striking in an even-numbered legislative off-year by leaning hard on sweeping executive orders and rejecting requests from both extremes of the political spectrum to call for a special session was right in line with his years-long effort to beef up executive authority in Texas. It was also apparently too much for state lawmakers to swallow.

Neither Abbott’s office nor Hidalgo’s office responded to requests for comment from the Houston Press about any of the pandemic-minded legislation working its way through the state Capitol that would limit their powers. Through a spokesman, Turner’s office declined to comment on any of the proposed bills.

The most high-profile bills of that nature filed so far — House Bill 3 and Senate Bill 1025 — would both limit both the powers of the governor and local officials to issue pandemic-minded mandates. Each bill was passed by the chamber of the Legislature it originated in; HB 3 hasn’t been debated by the Senate yet, and SB 1025 now awaits a hearing in the House State Affairs Committee.

Another bill written by Houston’s own Republican state Sen. Paul Bettencourt would strip local governments of the power to issue any criminal charges whatsoever tied to disaster-minded public health regulations, replacing them with civil penalties that would only total fines of $500 or less.

“Texans should never be faced with criminal penalties for ‘mask’ violations, EVER!” Bettencourt wrote in a statement after his bill was approved by the state Senate. It’s now waiting to be debated by the House Public Health Committee.

HB 3, written by Republican state Rep. Dustin Burrows, would still let future governors issue mask mandates and close businesses during pandemics. But after 30 days, those orders could only be extended with the approval of the Legislature, or by a new oversight committee if the Legislature isn’t in session.

This 12-member committee would be co-chaired by the lieutenant governor and the Speaker of the Texas House, along with an equal number of committee chairs from both the state House and Senate. It’s an interesting move, especially given how the even-number of committee members means tie votes would be possible.

Under HB 3, if a pandemic-related disaster declaration is issued by the governor, it’d have to be approved by the oversight committee after 30 days, and after 90 days, the governor would be forced to call for a special session of the Legislature to debate extending the disaster orders beyond that point.

The bill was supported by most Republican House members save for a few far-right lawmakers who thought the bill still gave too much power to the governor (an amendment to ban all future mask mandates failed to pass). A handful of Democrats supported the bill, but others were frustrated that it still allowed the governor to override local government pandemic orders, and because it would bar local officials from shutting down businesses as well.

House Democratic Caucus chair Chris Turner voted against HB 3 due to those limits to local power. “There’s one, in my view, fatal flaw that this bill has that just can’t be ignored,” he said while debating the bill. “That’s the continuation of an attack on local control and our local leaders.”

Over in the state Senate, SB 1025 wouldn’t just limit local officials’ and the governor’s powers during pandemics specifically, but would prevent them from ordering business closures altogether during any kind of disaster without approval from the Legislature. If the Legislature isn’t in Austin at the time and the governor thinks businesses should be shut down for safety reasons, or if the governor wants to declare a state emergency lasting longer than 30 days, SB 1025 would require a special session to be called.

SB 1025 was written by Republican state Sen. Brian Birdwell, who also authored Senate Joint Resolution 45 which would amend the Texas Constitution to give legislators the right to sue the governor in the Texas Supreme Court if a special session isn’t called 30 days after an executive disaster declaration is ordered. Even if the Texas House approves the Senate’s resolution to amend the state Constitution, it’d then have to be voted on statewide by Texans to go into effect.

Even though it's obvious that both the Texas Senate and House are keen to secure more power for themselves in future pandemics at the expense of the Governor’s Mansion and local officials, it’s still unclear whether the House or Senate approach will prevail given that neither chamber has yet considered the other’s preferred legislation.

While Abbott might quibble over just how much his authority should be limited, it turns out he’s not outright opposed to the Legislature encroaching on his turf around disaster response, probably because he realizes how popular that’d be with the right-wing Republican grassroots whose support he’ll need to win reelection in 2022. He told the Texas Tribune back in February that he was open to legislation to limit executive authority in future disasters, but did say that he wanted to have a say in crafting what those limits would look like.

If either HB 3 or SB 1025 gets approved by both chambers of the Legislature, Abbott would always have the power to veto whichever bill makes it to his desk, as he does with all legislation. If that happens, lawmakers could still force the bill into state law if two-thirds majorities in both the Texas House and Senate vote in favor of overriding Abbott's veto.

Since Abbott hasn’t publicly talked about either the state House or Senate’s pandemic bills, it’s unclear if he prefers one blueprint over the other. It’s also not clear if any of SB 1025 or HB 3’s language was crafted with input from Team Abbott behind the scenes.

One thing no one is really scratching their heads over is whether or not Democratic local officials like Turner and Hidalgo would welcome having even less power during future disease outbreaks. Even if they won’t say so on the record, it’s hard to imagine they’d be thrilled about being even less able to shape public health policy for their constituents, even if it’s the Legislature rather than the governor making those life or death decisions.

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

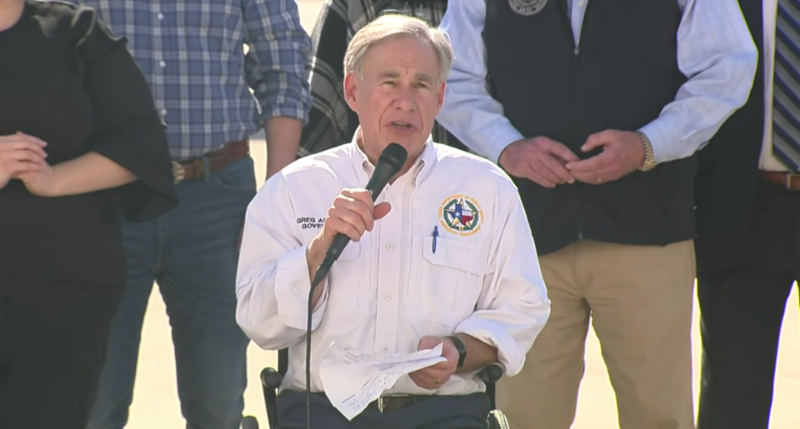

Is Gov. Abbott Willing to Give Up Power to Hold Onto His Job?

Screenshot

Gov. Greg Abbott dictated the state's COVID-19 response through executive orders, a power the Legislature hopes to reduce.

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

]