It was 1926 and New York Yankees General Manager Ed Barrow was concerned about the number of people in Yankee Stadium. Not his players on the field, but the empty seats in the stands that could be (and should be) filled by members of the ticket-buying public who might also purchase some popcorn.

Between the years of 1880-1920, more than four million Italians emigrated from their mother country to the United States, with many coming through nearby Ellis Island and choosing to stay in the city. The Yanks never had a player of Italian descent on their roster. But maybe if they did, it could open up a new fan base—and fill those seats.

Enter 22-year-old Tony Lazzeri, a minor league star player all the way across the country for the Salt Lake City Bees. Lazzeri got an offer to don the pinstripes and began a career that would see him put up then-pretty good numbers in the home run column. And his quiet and measured demeanor made him a team leader.

So enthused about seeing someone with Roots in the Boot playing Major League Baseball, that Lazzeri was even feted at banquets by proud local Italian-American clubs while playing on the road. And those seats at Yankee Stadium were soon filled.

“I learned so much by doing the research for this film. Lazzeri was also an epileptic, and nobody would touch him [in the majors] because they didn’t want an incident on the field,” says Roberto Angotti, Director/Writer of the documentary Italian American Baseball Family says via Zoom. “But Lazzeri brought people to the games. And all the Italians would [chant] ‘Push ‘Em Up Tony!’ instead of ‘Hit a Home Run!’”

Lazzeri’s impact on baseball as an ethnic representative—and that of other players like Tommy Lasorda. Roy Campanella, Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Tony LaRussa, Joe Torre, Mike Piazza and Frank Viola—are detailed in the documentary.

Italian American Baseball Family will screen at Italian Cultural & Community Center of Houston on February 22. It will be followed by a panel discussion and Q&A featuring Angotti, former Team Italy hurler and Cincinnati Reds pitcher A.J. Morris, baseball journalist David Fanucchi and Houston Sports Radio 610 Host Shaun Bijani.

“Baseball was a way for Italians to be accepted in popular culture and their neighborhoods. They weren’t thought of very well,” Angotti adds.

Angotti’s love of baseball began early. Growing up in the Los Angeles area in La Habra, he lived close to Dodger Stadium. Dodgers coach Tommy Lasorda was from the next town over in Fullerton and could be seen around the area. Angotti is also distantly related to Yankee great (and future Meat Loaf song narrator) Phil Rizzuto.

“Tommy loved fellow Italians and his Italian roots, and he’d go above the beyond to let you know that. It was great to watch him in action,” Angotti says. “Tommy was the fabric of Italian-American baseball in my era.”

Lasorda himself sat for Angotti’s camera in his home, and his recollections about Italian culture in the sport and individual players threads throughout the narrative.

Of course, one Italian-American baseball player did (and still) stands above them all. And that’s “Joltin’ Joe” DiMaggio, whose fame spread far beyond the baseball diamond and long after his playing days were over.

“He was an American icon on the cover of Life and married to Marilyn Monroe!” Angotti says. “DiMaggio opened the door on a massive level for Italian-Americans to assimilate into wider [society].”

But even The Yankee Clipper faced a challenge early in his baseball career—parental disapproval. As historian Lawrence Baldassaro (author of Beyond DiMaggio: Italian Americans in Baseball) notes in the film, many first-generation Italian fathers often thought about little else but work and providing for their families.

So, seeing their sons playing this kid’s game “baseball” was deemed a waste of time, when they could be getting a job. There was also no tradition of the sport (or much of any sport) in the Old Country.

“You can’t make a living playing baseball!” Joe’s father Giuseppe roared at oldest son Vince. Which didn’t bode well for Joe and youngest brother Dom, who were all obsessed with the sport as a possible career path.

Vince went away to play in the minor leagues. And when he came back in 1932 and spread his earnings of $1,500 on the family’s dining room table (the equivalent of more than $30,000 today), Dad suddenly came around.

“It wasn’t in [the older generation’s] dialogue or their vocabulary. They didn’t see it as legit. They needed to be helping out in the family store,” Angotti offers. “The Italians were working dirty jobs in the mines and the railroads and the [families] were sacrificing. This ‘stickball’ was not a career option.”

There’s a charming section of senior citizens in the Italian city of Nettuno recalling with wide-eyed enthusiasm decades later the time when DiMaggio came to visit the city of his ancestors. He belted out home run after home run against a great Italian pitcher in an informal exhibition. Some even still remember him dressed in plain everyday clothes—not the image of the Famous American Baseball Star they were expecting.

There’s also historical information about the Italian experience in America in the 19th and 20th centuries. Like during World War II with the U.S. fighting Italy, 600,000 unnaturalized Italian U.S. residents would have to register as “enemy aliens,” were not allowed to carry items like cameras or flashlights and had a curfew from 8 p.m.to 6 a.m.

Joe DiMaggio’s family’s own fishing boats weren’t allowed to head out to sea—they would be too close to military-sensitive areas and could be spying. Some Italians were even sent to internment camps.

Italian American Baseball Family also includes interviews that Angotti conducted with players and coaches from Team Italy. The international squad with rotating lineups plays in both the World Baseball Classic series and the Federazione Italiana Baseball Softball (FIBS)—Italy's equivalent of the MLB.

Angotti hasn’t given up the subject for his next documentary, Introducing Team Italy Manager Mike Piazza. Its soundtrack by world music artist Pato Banton, Baseball Reggae is already available for download with tunes like “Go Mike Go” and “Never Give in Piazza.”

Finally, there is some Houston connection to Italian American Baseball Family. It notes that while Joe DiMaggio was the first player of Italian descent to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, 12 others have followed. Including Houston Astros legend Craig Biggio.

“For somebody who converted positions and made a name of himself, he became the face of the franchise for the Astros. So how could we not bring this to Houston?” Angotti says. “And his son [Cavan], is also very talented in the Blue Jays organization. And you have others like Yogi Berra and his son, Dale. It’s going down the bloodlines.”

Italian American Baseball Family screens at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, February 22, at the Italian Cultural & Community Center, 1101 Milford. A panel discussion/Q&A follows. For information, call 713-524-4222 or visit ICCCHouston.com. $10 members, $15 non-members.

For more information on Roberto Angotti and his writings, visit MLBforLife.com

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

Italian-Americans "Play Ball!" in Sports Documentary

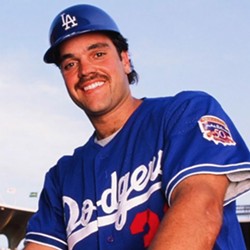

Photo by Peter McEvilley

Roberto Angotti at the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in Chicago, Illinois.

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

]