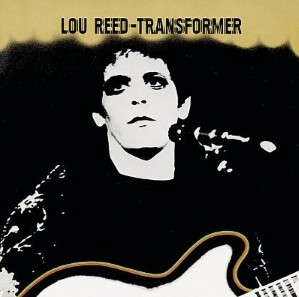

But there was more to it than a naughty “tee hee” regarding a blow job. Reed’s album Transformer (which contained “Wild Side”) provided both a rallying cry and a sense of affirmation for LGBTQ people of the day, most of whom were still closeted. This is the case that Simon Doonan makes in his new book Transformer: A Story of Glitter, Glam Rock, and Loving Lou Reed (HarperOne, 160 pp. $24.99).

Speaking from his home in New York City, Doonan recalls what it was like growing up gay in England. “Homosexuality was legalized in England in 1967. So those of us growing up in the ‘50s and early ‘60s lived with this shadow of criminality over us. And it was categorized as a mental illness. Back then, people thought that if you were homosexual, you were doomed to be blackmailed, beaten up, to just having a really miserable, unhappy life. So we had to figure out a way to live, to find out who we were.”

Transformer is part memoir, part cultural analysis. Doonan was raised in Reading, a town on the river Thames, about 40 miles from London, so he was in the midst of glam rock’s early stirrings. Prior to that, Doonan writes, any flamboyant tendencies had to be concealed. “In the ‘60s, I developed a habit of mincing round the backyard in the style of the Ballet Russes with a dollop of Carmen Miranda. On rainy days, my best friend and I busied ourselves putting on fashion shows in my attic, wearing my mum’s clothes. I was not out. Nobody was. Being out wasn’t a thing back then.”

Doonan was soon enough taken aside by his father, who suspected “that there might be a pansy among the begonias.” While gazing out a window overlooking (ironically) Reading Gaol, the facility where Oscar Wilde was imprisoned after conviction on a charge of “gross indecency,” the older man expressed concern over what life might hold for his son. Doonan’s mother, on the other hand, was resolutely supportive. When told that her son was being bullied at school by the other children, she said, “They’re all ugly so who cares what they think?”

By the time Marc Bolan and David Bowie began to create the nascent glam scene in London, Doonan was old enough to take the train and catch some of their shows. He was also drawn by an article in the tabloid News of the World which described an active cruising community. The piece was intended to frighten responsible Londoners, warning them of the dangerous, immoral activities taking place all around them. Naturally, it had the exact opposite effect on young Doonan, who says, “I distinctly remember being enthralled by the description of this alternative gay utopia.”

Lou Reed’s album Transformer was created in this milieu. According to Reed, “I thought it was dreary for gay people to have to listen to straight people’s love songs, so we created this.” Reed was at loose ends after leaving the Velvet Underground when he was approached by David Bowie, a Velvets fanboy. Bowie was riding high after the release of his Ziggy Stardust album and had the juice to convince his record company to back a Lou Reed album that he would produce.

“Bowie introduced me – and everybody else – to Lou Reed,” Doonan says. “He was a big proponent of the Velvet Underground. Bowie would have Lou come up onstage, and they would do ‘I’m Waiting for the Man’ together.”

Bowie was already a gay icon. According to Doonan, “Bowie dangled his feather boa from on high, and in dire need of a lifeline, we grabbed onto it.” He continues, “Many gays of my generation lived in terror of becoming a sad cliché, a lonely old poofter, knocking back gin and tonics while listening to scratchy recordings of Judy Garland. Bowie opened the door to a world where personal expression was unlimited. It was more than, ‘Even though you are different, you are OK.’ It was, ‘You are different, and guess what, that is a colossal advantage, which, if you throw your fascinator into the ring, will enable you to construct a fabulous life.’”

Growing up, Doonan looked to window dressers in Reading as examples of what a fabulous life could be, also taking inspiration from Coco Chanel. “She said, ‘My life did not please me, so I created my life.’ I think that’s a very resonant quote for gay people growing up in the mid-century and before. You had to create your own life. When you look back, you think, ‘God, people were so good at it.’ They moved to the big city, became professionally successful, fought prejudice, made prejudice irrelevant. When you think about the number of gay people who grew up at that time and what they accomplished – men and women – you think, ‘Wow, these people really are resilient in the way they created their lives, because they had to.’”“I thought it was dreary for gay people to have to listen to straight people’s love songs, so we created this.”

tweet this

Cultural touchstone though it may be, when Transformer was released, it was not a hit with the critics.

“Rock and roll is still identified with the very macho guitar god,” Doonan says. “It is fundamentally still very much a binary world. Even during the hair metal years, when they all had long hair and outrageous outfits, it was still very butch, for want of a better word. Rock and roll has always been that way, and I think that was a bit of a problem for Lou, because he went to London and dived into this world of glam rock. And back in America, the rock establishment didn’t know what to do with this new kind of androgyny and the makeup and the painted fingernails. They used it as an opportunity to criticize him. And that’s what Lou came up against with Transformer.”

However, those in the target demographic connected with the material immediately, identifying and understanding on a deep level. “For the fans, it was just massive,” Doonan recalls. “They loved it, and they continue to love it. The general public should be listened to more and the critics probably less. They’re looking for something to have a go at, and this album was an easy target, because there was a sense of fun and frivolity about it, which, to me, was so important. And in a way, profound.”

So, 50 years later, what is Doonan’s favorite song on Transformer? “It’s hard to pick, because it’s so magnificent, and the songs are so different from each other. If I had to take one to a desert island, probably “Satellite of Love,” Doonan declares after a moment of reflection. “I love that song, and you get to hear Bowie on it. The words and the diction, it’s so clear. You don’t have to read the words on the back of the album.” Of Transformer on the whole, Doonan says, “There’s this dark poetry — right from the source, one of the heaviest guys in music ever – juxtaposed with this lightness and bounce that Bowie had. That’s what makes it great for me, and why it has been such an enduring album.”