Marc Myers has an enviable gig. Writing for the Wall Street Journal, he has, for the past ten years or so, authored columns focusing on classic songs, talking with artists ranging from the Beach Boys to Alice Cooper to Elton John. Hot on the heels of his pop culture history Rock Concert, Myers has just released Anatomy of 55 More Songs: The Oral History of Top Hits That Changed Rock, R&B, and Soul (Grove Press, 354 pp. $27), the second of his books collecting the stories behind beloved hit songs.

So what’s it like, spending your days talking to rock stars? “It’s funny, those who are not in the media think these people are on my speed dial,” Myers says, speaking from his home in New York City. “And if I call Keith Richards, Keith is going to answer on the other end and, like he’ll see my number coming up and get on right away, and if I want an hour of his time, he’s happy to give it to me. It really doesn’t work like that.”

One thing that distinguishes Myers’ reportage is the fact that the stories are presented in an oral history format. Initially, the song columns followed a more traditional style, but Myers decided that the former approach was more compelling. “The quotes were so interesting,” he says. A decision was made “to let the artist or those responsible for writing and recording the song and creating it, for them to tell in their words how that came to pass.”

Which doesn’t mean that Myers merely transcribed interview recordings. “That’s kind of a simplification. Because, if we just let the subjects talk, we would have 17,000 words.” That’s a bit long for most publications. In fact, Myers says that his editors were looking for columns more in the range of 850 to 900 words. “And it wouldn’t be much of a story, because most of these guys are not so much storytellers as they are amazing musicians who can take a song and make it so that 300 million people love it. But an unfolding story in print? That’s different.

“It required me to use their words as paint on a canvas, so to speak, to create a narrative that the reader would find compelling. I treated it like a screenplay. They should all be highly visual, meaning that you can see what’s happening, and they all feel like mini movies,” Myers explains.

“I open loud, I open big. There are a couple of turning points in the story most of the time, and it ends poetic. I always shoot for that. Can’t always get there fully, but I always try to make it so that the reader is fascinated not only by the song story, but fascinated by the column’s approach to telling the story.”

Myers’ process of selecting songs to profile involves walking the line between familiar and overplayed. Fitting within this category are “The Weight” (The Band), “Bad Moon Rising” (Creedence Clearwater Revival), and “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” (The Temptations).

“I wanted to choose songs that would be well-known but were on the service road,” he says by way of automotive analogy. “I didn’t want to choose main highway songs. I wanted to choose interesting tourist places that people knew but that they forgot about. I wanted something that, when you saw the title, you would say, ‘Oh, I love that song!’”

That goal has certainly been achieved in Anatomy of 55 More Songs. All of the songs profiled would be characterized as “popular music,” but the breadth of styles is impressive, with the Charlie Daniels Band’s “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” sitting comfortably beside Gary Numan’s “Cars.” The book, arranged chronologically, moves from “Dancing in the Streets” to “Sunshine Superman” to "Truckin'" to “Smoke on the Water,” with surprises tucked in along the way.

When conducting the interviews that provide the book’s content, Myers put in plenty of homework time beforehand. “It’s not good enough for me to go in with what I know,” he says. “That’s called Wikipedia journalism. I did a ton of research before I did any of these.”

The Wall Street Journal column finally came to an end, and Myers switched from singles to albums for a new series of stories. “After 10 years, I had interviewed everybody I was going to get. Dylan said yes, then said no, then said yes, then said no. I guess I fared better than the Nobel committee for a period of time,” he says with a chuckle. “It’s not enough just to go in and ask the questions that will produce the answers that are known. I would go beyond what was known. I’m capturing the story of their songs, but at the same time, I’m creating a narrative. There’s always an unearthing.”

It seems that one function of the columns is to unlock memories and emotions that may have been buried for years. A bit of a Proustian thing, perhaps? “There is a madeleine quality to it,” Myers says. “Your youth, little by little, becomes the good old days. Life always seems to get more difficult and more traumatic. This isn’t a new phenomenon. I think people in the 1880s yearned for the 1840s. I think people in the 1840s probably said, ‘Oh, when we were young, when the British ruled us…’ I think everybody looks back at a slower time, a childhood time, when life seemed a whole lot simpler. What these songs trigger in us is a sense of when we were much younger and life wasn’t as complicated. It takes us back to a memory that, rightly or wrongly, becomes golden.”

So if Myers doesn’t have rock stars on his speed dial, how do these revelatory interviews happen? He says that it comes down to relationships with managers, publicists, and PR people. “They need to know you’re not going to spill the wine all over the place or start screaming at the dinner party. They need to know that you’re going to come and do a high-level job. They know that I’m a highly interested party who is going to turn what they’re going to tell me into something that’s historically valuable,” he says.

“I’m not a fan at all. I’ve never cared about that stuff. I only care about the art. I’m not interested in the dish, the dirt. I’m not interested in any drugs. I’m not interested in the garbage. I’m just interested in how art was created. And it is art when you get to that level. I only want to know how the art was created. That’s it.”

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

Anatomy of 55 More Songs Goes Behind the Scenes of Our Favorite Records

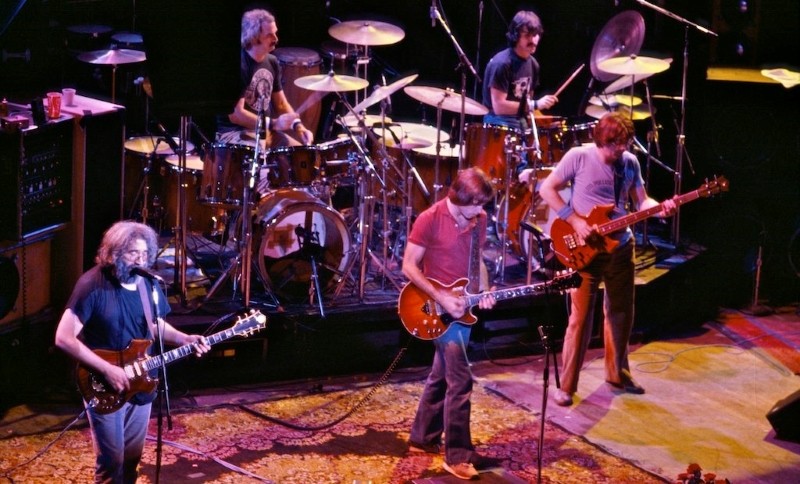

The Grateful Dead is among the bands and artists showcased in the new book Anatomy of 55 More Songs: The Oral History of Top Hits That Changed Rock, Pop and Soul.

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

]