Many years ago, I read a review of a Neil Young album that began with the writer saying something like, “If Neil Young were to take a crap in a paper bag and sell it, I would be first in line at the store.” Such was the devotion that many felt for the warbly-voiced Canadian during the groovy ‘60s and the mellow ‘70s.

Things took a turn for the weird when Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980. Was the timing merely a coincidence? Hard to say. Young had already shown a propensity for confounding expectations, mixing acoustic singer-songwriter tunes with feedback-laden recordings that journeyed into hard rock territory. But as the ‘80s picked up steam, Young began to release albums that were, at the very least, curious. Most notorious was Trans, which incorporated electronic effects and vocal processing, an effort dismissed by many of the faithful as “computer music.”

Then came Everybody’s Rockin’, an excursion into hardcore rockabilly which represented a major passive-aggressive move after Geffen Records requested a “rock and roll” album from Young. Label head David Geffen eventually sued Young for delivering “uncharacteristic” and “unrepresentative” albums. In essence, Young was sued for not sounding like himself.

Since then, Young has, artistically speaking, wandered hither and yon, releasing over two dozen albums ranging from “old school” efforts like Harvest Moon to environmentalist screeds like Greendale (which was also technically a musical, though not of the Rodgers and Hammerstein variety). More recently, he has railed against agribusiness, Starbucks, and big box stores, writing songs that have no subtext, broadsides that leave no room for interpretation. At some point, Young truly reached the “crap in a paper bag” phase of his career.

Which is why the release of a Harvest 50th anniversary box set is so welcome for those of us who loved the Neil Young of Everybody Knows This is Nowhere, After the Goldrush and even Tonight’s the Night. Harvest is one of Young’s most beloved and best selling albums, so why wouldn’t we want to hear more?

Young has always been meticulous (obsessive?) when it comes to preserving his legacy, resulting in a collection of archives that contains thousands of hours of studio tracks, live recordings, film, and video. He has begun releasing this material at an increasing rate over the past several years, much to the delight of many old-timers. Two live sets dating from the early ‘70s are set for release next month.

In addition to a remastered version of the album, we get a CD containing outtakes from the Harvest sessions, plus CD and DVD versions of Young’s 1971 appearance on a BBC television program. But the most valuable component of the new set is the documentary Harvest Time, shot during the recording of the album and directed by Young under his nom de cinema Bernard Shakey. The film captures a moment in time when Young was at a creative and commercial peak, living the life of a “rich hippie” (his term) on his Broken Arrow ranch in northern California with actress Carrie Snodgress (Diary of a Mad Housewife).

The first portion of the doc takes place during recording sessions at the ranch, where Young has assembled some hotshot Nashville musicians (bassist Tim Drummond, drummer Kenny Buttrey and multi-instrumentalist Ben Keith), plus L.A. studio rat / Phil Spector protege Jack Nitzsche. The ranch itself appears to be in remote territory, and the studio is located – quite literally - in a barn. The atmosphere is one of granola and flannel shirts.

Stylistically, Young / Shakey appears to be a devotee of the cinema verité aesthetic, though at times a viewer might question whether it is a matter of philosophy or sloppy technique that gives the film its look. There are brief interview segments with some of the participants, but much of the time is spent watching the band jamming away as the tunes take shape.

Then, suddenly, we are in London. There is no explanation given for the change in venue, but it soon becomes apparent that Young has booked the London Symphony Orchestra for a recording session, feeling perhaps that his song “A Man Needs a Maid” requires an orchestral framework upon which to hang some of his more questionable – though Young now says “misinterpreted” — lyrics. The less said, the better, as the song has aged about as well as a banana.

The cut — from a shot of the band playing among hay bales to a shot of Young at a grand piano surrounded by orchestra musicians – points up the problems inherent when attempts are made to combine rock and roll and classical music.

To a great extent, it is a case of conflicting philosophies. Due to the very nature of orchestral music, a premium must be placed on precision in order to properly harness the sound of dozens of musicians performing simultaneously. Conversely, rock and roll values spontaneity and a certain organic looseness. When these conflicting ethoses are brought together, the whole becomes less than the sum of its parts.

An impending train wreck is foreshadowed by conversations between a persnickety Young and a game but somewhat clueless conductor David Meecham. At one point, Young inquires, “Have you ever heard of Merle Haggard?” Later, Meecham mentions that the orchestra has recently worked with Pink Floyd, remarking, “They make some good noises. You might hear of them.” The conductor feels the need to explain a tricky time signature to Young, who replies in an exasperated tone but with a smile on his face, “Yeah, I wrote it!”

Young is an instinctual, visceral musician, and even with Nitzsche (who provided the orchestration) and esteemed British producer Glyn Johns (the Beatles, the Stones, the Who) along to keep the peace, he encounters problems when attempting to sync up with the orchestra. Lots of talking with little understanding, like many a band rehearsal. Nitzsche: “Well, that’s up to Neil.” Conductor: “I don’t know what he wants.”

During a break, Young and his crew sit around slamming tall boys as Nitzsche tries to elucidate the difference between “rock and the symphony thing,” saying, “They pay no attention to pulse that way. It’s strictly on the sheet.” He concludes his explanation with a shrug, muttering “And you know, that’s not like Hollywood.”

The recording process is frustrating, uncomfortable and maddening to watch, but sitting through the sometimes excruciating experience deftly exhibits the way in which Young and his creative contemporaries view the world. We get to experience what it’s like to work with Young, an artist who is notoriously mercurial, changing his mind in an instant.

Then it’s back to the States and the friendly confines of recording studios as work continues on the album. Particularly exhilarating are the scenes showing Young and colleagues Graham Nash and Stephen Stills overdubbing vocals on “Words.” Nash is the disciplinarian, taking great satisfaction in precisely tweaking the harmonies. Stills is the clown, keeping everyone loose. Young is somewhere in between. They were at the height of their fame, they were good, and they knew it.

The film continues with more jamming, this time at a studio in Nashville. These moments ably demonstrate that you can’t force inspiration to strike. You just have to keep playing and hope that something good happens. As a musician friend of mine once said, creativity is an incredibly inefficient process.

Regardless, the musicians seem happy and satisfied. In a brief interview, Ben Keith speaks positively about the experience, saying, “Recording with Neil? Oh, it’s a ball. I love it.” Later, he says, “It took me back a few years. When you used to play, you used to have a lot of fun with it, maybe sitting on the front porch. In recording nowadays, like Nashville, like here, it’s like a gig, like a job. And that’s not cool. And it’s not any fun.”

After listening to a playback of “Words,” head in hands, completely immersed in the music, Young looks up and says, “I think we could probably play it better. I have no doubt that we’ll play it better than this. But I don’t think it makes any difference to the record. It’s so rough. I kinda like that.”

A highlight of the film is a visit Young pays to Nashville disc jockey Scott Shannon. The on-air interview is mildly humorous, but the segment hits its stride during an encounter between Young and Gil Gilliam, a remarkably precocious 13-year-old who is working at the radio station, answering phones and helping out wherever he can. The kid is a hoot – mildly obnoxious, as many 13-year-olds are – but Young treats him with courtesy and respect as the lad interviews him on a variety of topics, including the then-recent Beatles movie Let It Be.

Harvest Time will be considered by some to be an overly-long, meandering home movie, but I suspect that Young was up to something more, attempting to make a statement on the creative process, stardom and the virtues of individualism. However, in his radio interview with Shannon, Young says, somewhat disingenuously, “We’re just making a film about — I don’t know — just the things we wanna film. There’s really not a big plan about it or anything. I’m making it like a make an album, sort of.”

Young does offer a revealing glimpse toward the end of the film. When asked about some of the imagery in his lyrics, Young says, “I really don’t know where that comes from. I just see the pictures in my eyes. All of a sudden it comes, and it just comes gooshing out. It’s like having a mental orgasm.”

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

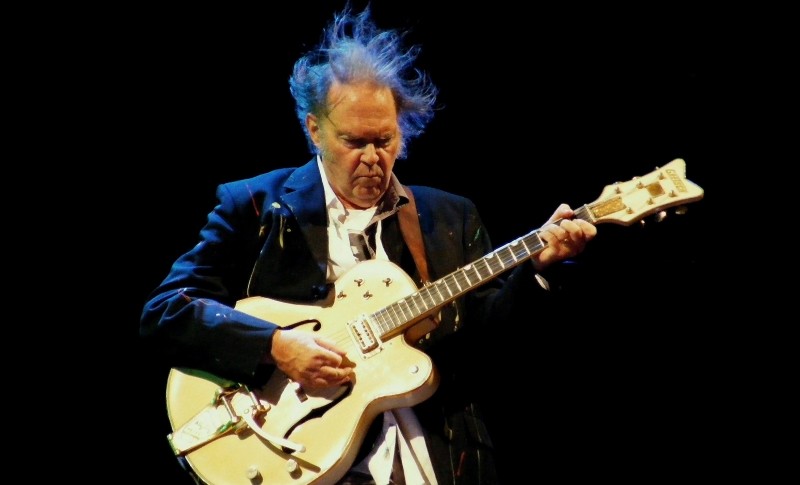

Neil Young Revisits Harvest, Generating Plenty of Wheat and Little Chaff

Neil Young, seen here delivering a hair-raising live performance, has released a 50th anniversary edition of his classic album Harvest which includes outtakes, television performances and a documentary film.

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

]