The year 1971 saw him at one of many career crossroads: Crosby, Stills, Nash (and now Young) had released the epochal Déjà Vu the year before, which also saw the release of his first solo record. Follow-up Stephen Stills 2 had just come out, and he was months away from forming the supergroup Manassas.

So, he embarked on his first solo tour—albeit with a number of band members in tow, including the Memphis Horns section—and it found him stopping at the 3,500-seat Berkeley Community Center on August 20 & 21. A 14-song document of the evenings, Stephen Stills: Live at Berkeley 1971 (Iconic/Omnivore Recordings) is set for release this week.

Sitting outside the Center in a mobile van from the storied Wally Heider’s Studios and connected to the band’s microphones by hundreds of feet of wires and cables was sound engineer Bill Halverson, who recorded every note. “I have a vague, almost non-existent memory of those particular gigs. I don’t have my day planners from that time!” Halverson laughs today.

“But I have my name on a couple of the tape boxes, so I must have been there! I certainly spent a lot of time with Stephen over the years.”

Halverson doesn’t think that Stills recorded the shows with the intention of releasing a live record, but probably wanted some document of it, especially given the lineup of players onstage.

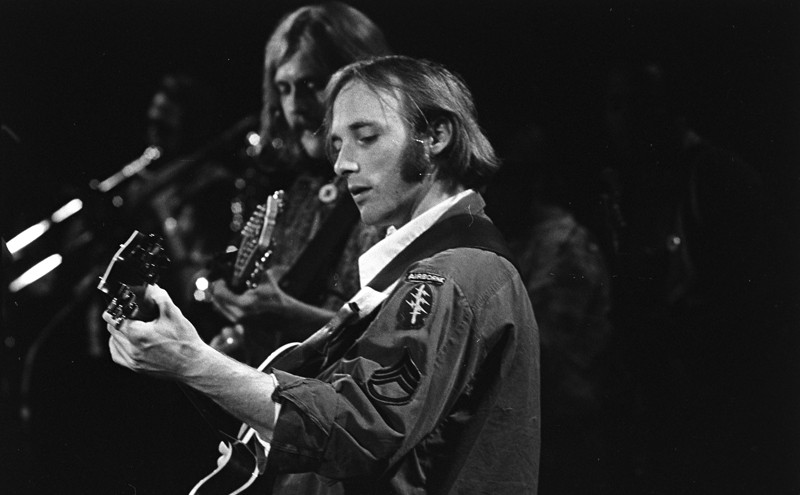

Drummer Dallas Taylor on the '71 tour, who Stills calls "his brother" during band introductions on the record.

Photo by Henry Diltz

Stills’ band for the night included country troubadour Steve Fromholz (vocals/guitar), Sidney George (alto sax/flute) and four musicians who would soon join him in new band Manassas: Paul Harris (organ), Joe Lala (congas, percussion), Calvin “Fuzzy” Samuels (bass), and Dallas Taylor (drums).

The Memphis Horns appear on selected cuts, and included Jack Hale, Sr. (trombone), Roger Hopps (trumpet, flugelhorn), Wayne Jackson (trumpet), Andrew Love (tenor sax), and Floyd Newman (sax). Stills’ once-future-once-future bandmate David Crosby sings and plays acoustic guitar on two cuts, Stills’ “You Don’t Have to Cry” and his own “The Lee Shore.”

Highlights include a country waltz “Jesus Gave Away Love for Free,” the frenetic, syllable-spouting “Word Game” (Stills second famous foray into protest songs after Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth”), and a gospel-like, plaintive love song “Sugar Babe.”

But what makes Live at Berkeley 1971 truly different and special from a regular Stills’ live set or recording is the presence of the Memphis Horns. The collective was famous on their own right having backed so many performers at Stax Records as well Al Green and Elvis Presley.

They transform the material they’re on and give it a sonic punch it wouldn’t otherwise have. And the rest of the band are clearly pushed ahead in their own playing as well. “Lean on Me” (not the Bill Withers tune), “Ecology Song,” and “Cherokee”—the last a nearly 10-minute opus with ample horn solos—simply sizzle.

Steve Fromholz (left) with The Memphis Horns and bassist Calvin "Fuzzy" Samuels on the '71 tour.

Photo by Henry Diltz

“People always said how come songs like ‘Johnny’s Garden’ and others weren’t on that second record,” Halverson says, noting several of them ended up on the first Manassas release. “And Stephen said if you put all the good stuff on the second album, some of them might get [buried] and not heard.”

In addition to working with Crosby, Stills and Nash both collectively and individually, Halverson has sat behind the control board for live and studio records by Cream, America, the Beach Boys, Bill Withers and even Kraftwerk. He also helped Heider record the historic 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. After that, he and Stills had worked on some of his solo demos—including an early version of “49 Bye-Byes.”

Later, he was called in to engineer the debut record what Stills called “his new group.” That would be Crosby, Stills and Nash and their resulting self-titled 1969 record.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into or if they had rehearsed, but the three of them showed up coming out of David [Crosby’s] VW van and Stephen had a guitar. I had already done a demo with David and Peter Tork [of the Monkees] on a folksinger named Judy Mayhan, and then they introduced me to Graham [Nash],” Halverson recalls.

Stills wanted to take a crack at a new tune he’s worked up. Asking the engineer to turn out the lights while Crosby and Nash were in the control room with Halverson. “The guitar sounded really dull, so I’m adding top end and taking bottom off and putting a compressor on it just trying to get some edge so it didn’t sound like a big tubby Martin guitar,” he says. After some further adjusting, Stills ran through the song solo.

“I turned back around, and Crosby had his arm in the air to signal recording and Stephen starts to play. I couldn’t see him, but I could sure hear him. And now it sounded really bright,” he says.

“And then [Crosby and Nash] started to dance along with it. After seven and a half minutes, I thought I had messed it up. But they gave each other high-fives and Stephen came in and leaned across the desk and he said ‘That’s the sound I’ve been looking for! Nobody would let me do it!’”

And that song? “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” One of CSN’s best-known and most enduring tracks and Stills’ tribute to his then-girlfriend, folksinger Judy Collins.

Halverson said he’s “never worked with someone” who had so much music in his head as Stephen Stills, who always wanted to record it as quickly as possible as if the muse might leave if he waited any amount of time. He adds that Stills would just lay down “idea after idea after idea and overdubs” and only after he was done then listen to it all.

“I kept up with him. I mean, David would be asleep on the couch and Stephen would just work into the night. And one thing I learned from Wally Heider is that you always record. Always. You never know when you’re going to get something that [can’t be] repeated.”

Finally, the now 81-year-old Halverson mentions that did get to see his friend, the now 78-year-old Stills, late last year when Halverson was in Los Angeles doing some on-camera interviews for a CSN documentary that’s in the works.

“After I finished, I went up to Stephen’s house and spent a few hours with him. The first time we’ve really sat down since 1999 when I worked on the [CSNY] record Looking Forward,” Halverson says.

“He’s older and a bit hard of hearing, but it’s the same Stephen that I know and love. I’m grateful to have worked with someone who had that amount of talent. And we did a lot of recording that hasn’t seen the light of day yet!”