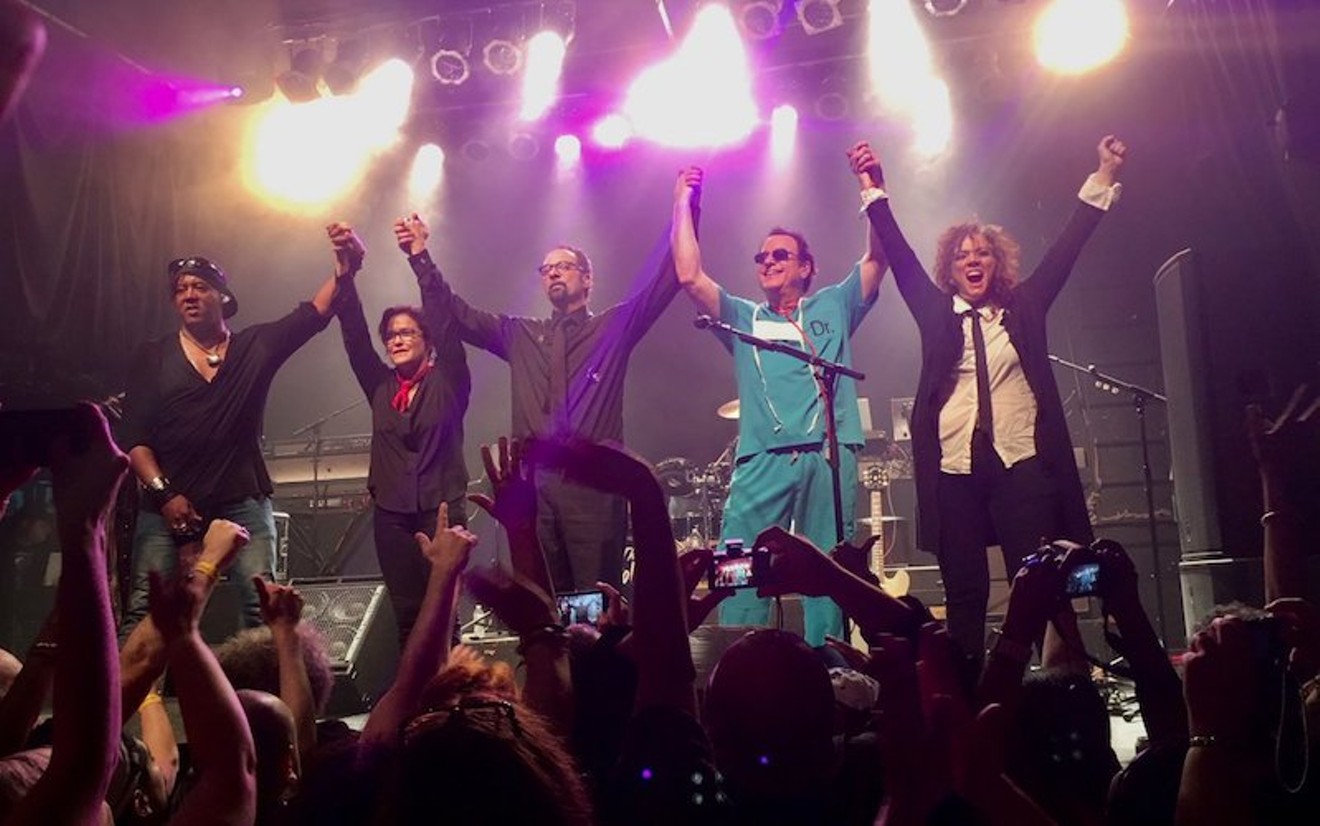

Even as Prince ascended from precocious teenage prodigy to certified Rock God, Bobby Z. was there on the drums. It’s been nearly 14 months since Prince left us, and it still doesn’t feel real. Not to Bobby, not to his bandmates Wendy Melvoin, Lisa Coleman, Doctor Fink and Brown Mark. As his disciples within The Revolution, it was this band and its expansive sound that braided together pop, rock, funk and R&B for the albums Purple Rain, Around The World In a Day and Parade. Now they return to Houston for the first time in 32 years tomorrow night, as part of a reunion tour that is equal parts remembrance and catharsis.

Bobby Z.’s voice carries plenty of hurt and sullenness and when he speaks of Prince, he does it with a firm grasp on what it entails. “We’re coming back but without him,” he says of the current tour. “This is a totally different thing. I feel like I need to do it to keep him alive. But we all know he’s gone.”

Thirty-two years ago, Prince and the Revolution took Houston for the very first time. On the twelfth day of January in the year of our Lord 1985, the home of Akeem (the Dream hadn’t adopted the H yet), now Joel Osteen’s present-day church, was turned into a cathedral drenched in purple, loudly rocking all night. Night after night for 11 days. Even the nearly impossible to replicate guitar solo from “When Doves Cry,” which, Bobby states matter-of-factly, could be played without any assistance of a backing track.

“I don’t remember playing Houston after Purple Rain,” he says. “But The Summit? That was 11 nights! We got a mind-boggling reception and it was such an incredible feeling that we got to come down to Texas and play. It was a big moment for us to play that many shows in one city. We had done some multiples, but that one stay … it was remarkable.”

Prince (and Wendy) at The Summit, January 1985

Photo by Bruce Kessler/Courtesy of rockinhouston.com

The Revolution will return to Houston on Thursday on a tour that Bobby calls a “funeral every night,” especially when the opening chords of “Purple Rain” play. “It feels like we’re at the end of the service and here’s this song,” he says. “But the look on people’s faces, the tears rolling down their cheeks? ‘Landing,’ as Wendy calls it. Giving people a landing.”

The spunky voice from Wendy & Lisa that wanted to play their records whenever Prince was late in the film, Melvoin took over as the leader of The Revolution. Being second in command to arguably the greatest guitarist who ever lived is a damn fine accomplishment in Bobby Z’s eyes, seeing that she’s been here ever since she snuck into a Prince show in Los Angeles at 13 years old.

“She doesn’t miss a lick,” he says. “It’s intimidating, but he’s not here. We’re not going to put somebody else up there. It’s just the five of us struggling to get through this. Is it going to be perfect? No. Is it going to be us, Prince and The Revolution giving that freight train of energy that only we can do? Yeah. You’ll get a feeling of it … it’s like watching James Brown’s band play without James’ groove, you know? You’d still be grooving but it’s not the same.

"We gotta remember him in the only way we know how, by creating the vibrations," Bobby continues. "When you hear 'Baby I’m a Star' live or 'Let’s Go Crazy' live, you hear it as if you’re hearing it for the first time again. So the music of it live is uplifting because it’s still Prince’s music. These are notes on pages that he wrote. All you have to do is transcribe it. This is his music, he was a composer and people need to live it. We’re doing it in a way that gives you goosebumps and it gives us goosebumps and that makes for a great evening.”

The greatest task for The Revolution onstage is to play what could only be described as a New Orleans’ style funeral. The attention to detail Prince took in his live shows, the specificity of the drum programming or chords, and more, was matched by his intensity to craft perfection in the studio. It’s a challenge The Revolution has taken head-on throughout this tour, combing through a songbook that starts somewhere around the late '70s and only climbs upward. For two hours, the band chases around the bread crumbs of records that already had great arrangements, only taking out songs they couldn’t do without “The Greatest Screamer in Rock and Roll History.” No one could touch “The Beautiful Ones” or “Darling Nikki,” but “When You Were Mine” and others have made the cut.

As words have picked up about Prince, his status as a musician has been validated time and time again. To many, he’s the modern-day Mozart, a composer without peer with an unmatched work ethic. The Revolution were the first generation of musicians to study underneath him and learn his craft. If anyone knows his works, right down to the drum notes and how various parts plug in, it is them. But Prince’s death has made Bobby Z and company not only relish the moment but be aware of their own mortality.

“We’re not going to live forever either,” he says. “We want to carry on this music as long as we’re alive, you know? Cause that’s not forever either. It’s a beautiful thing that the five of us are still here … that still want to hear his music. This is something … I knew him since I was 19 years old. This man is a huge part of my life in a parental sense. This music needs to be played correctly. This is what he would want. The remarkable thing about Prince is that with all that volume and haze of all those people on stage and all the chaos he created … he was always in perfect pitch. And his vocals were never off. Ever. Rehearsal, gigs, just always in perfect pitch.”"These are notes on pages that he wrote. All you have to do is transcribe it." — Drummer Bobby Z on keeping Prince's music alive

tweet this

A Prince rehearsal would feel like a “union gig” in Bobby Z’s eyes. You’d clock in at 10 a.m., play material, get a lunch break and then come back around seven. “It’s like a NFL training camp setup,” Bobby says with a laugh. “Only difference is we’d be in these warehouses outside Minneapolis and he would hang big theater curtains up. That was genius! He instinctively knew how to do this stuff, to decorate and it was an incredible way of living. Every aspect down to your coffee mug is perfectly feng shui.”

Feng shui, however, was not part of Prince’s aesthetic when the two first met. Two years Prince’s senior, Bobby and Prince met in an era well before 10,000 people would flock to a Guitar Center and self-describe themselves as musicians. Well before Brown Mark made Prince pancakes. They were out of high school, not famous and still trying to make noise in Minneapolis.

“We took a pride in it,” Bobby recalls. “André [Cymone] and Prince were…they were going on. I came out of my high school, St. Louis Park High School, and me and Matt [Doctor Fink] would go on. It was a clash of the musicians at Moon Sound, Chris Moon’s studio that he played at. So when Prince got to Owen Hunsey, his first manager, I was working for Owen, driving around, advertising copy and photos at an ad agency he had. So I was with Prince night and day for seven months. Then I auditioned to be his drummer constantly. It wasn’t until Valentine’s Day of ‘78 until he welcomed me in.”

He continues: “Immediately when I met him is when I knew he was different. At Moon Sound, the first studio he played at and where he recorded his demo at, I was in the back as a studio drummer. I walked by the hallway and I saw the Afro. Then I heard the glorious music and I turned my head and said, ‘What is going on?’ And he was as shy and strange and wouldn’t even look at me. ‘What is going on here? Who are you?!’ And I just exuberated myself all over him and I continued to do for 43 years and made him laugh.

"Then he sat down and played me the whole thing," Bobby says. "The next night I came back watched him record a song. He said, ‘I want you to work.’ He did the drums, then the bass, then the keyboards, then the guitar and then he sang. It was 'Baby' and I was blown out of my mind. I screamed it from the rooftop that it took 20 or 10 or 5 to figure it out. I was the first disciple. I was John the Baptist.

“Instantly, we had to get a deal and we had to work hard like everybody else," he adds. "We all know nobody worked harder than him. He was gifted, but nobody worked harder than him. He drove himself to the point of perfection that had perfection. So it was like a circle.”

The establishment of Minneapolis as a rock outpost started at Moon Sound and spread outward. To First Avenue, the building that was made iconic in Purple Rain and Paisley Park, which is now a museum in Prince’s honor. The Revolution played Paisley Park on April 21, the one-year anniversary of his death, and First Avenue last Labor Day. Still inside Paisley Park lies Prince's mythical vault, an area containing enough unreleased music to give to fans for decades. Bobby knows he played on some of the material that lies within the vault but hopes that any releases are done in such a way that each piece or product gets its proper respect.

“I think what’s going to happen as years go on is that the same way they do Mozart in Vienna, it’ll be a big deal,” Bobby says of Paisley Park. “Thirty, 40, 50 years from now it’ll be an even bigger deal. This myth is of the old masters in the 17- and 1800s. Prince had a lot of that Old World with him; the knowledge of ages. And he presented that in how effortlessly he could play these instruments and write these songs.”

There are stories about Prince’s role as a taskmaster for any of his bands, the levying of fines for messing up during a show or rehearsal. The band still plays as if messing up once onstage will incur his side-eye glances and corrections. He knew that regardless of how talented he was, how incredible a soloist he was on any instrument, he needed a band in order to fully flesh his aesthetic out. In Bobby Z’s eyes, seeing that he was part of every album leading up to The Revolution; it was making a road by cutting down trees. By cutting down the trees, the end goal was to create and mold a garden.

“It was a tremendous amount of originality and effort going into it from all of our parts that he demanded,” Bobby says. “The Revolution is the last band he was in as a member, if you know what I mean. I don’t mean, ‘Well, he wasn’t in the NPG,’ but Prince was really a member of The Revolution; that’s what made it incredible. He was the leader of The Revolution, let’s make no mistake. But he was a member, too. It was cool and we were a gang and it worked and it was just spectacular. It’s visual, it’s musical personality, it’s men, it’s women, it’s black, Jewish, it’s gay, it’s straight, it’s everything. It’s life. And that’s how it picked the band and made it happen.”

The Revolution performs Thursday, June 15 at House of Blues, 1204 Caroline. Doors open at 7 p.m.