Much like its sibling network MTV’s VMAs, the CMT Music Awards are full of live performances by artists whose videos the network otherwise considers an afterthought. The “M” on CMT is confined to the hours of 4-8 a.m., mostly, plus its Top 20 countdown on Saturday and Sunday mornings. The rest is demographic-appropriate sitcoms like Reba and Roseanne, reality shows, weekend movies and ABC escapee Nashville, which just started the second half of its first season as CMT’s flagship original drama. Co-star Charles Esten hosts tonight’s awards, starting at 7 p.m.

Still, CMT is not so neutered that it’s completely ignorant of the past, which is why tonight’s show will include a salute to the late, great Gregg Allman, who passed May 27 at the age of 69. Allman was a survivor of all manner of addictions and one of the rock era’s most gifted keyboardists, fluid as a jazz pianist and funky as a church organist. As lead singer of the Allman Brothers Band, he channeled the seething heartache and randy energy of old bluesmen like T-Bone Walker, Elmore James and Muddy Waters about as well as anyone else ever could.

At tonight’s awards, he’ll be the posthumous beneficiary of one of those customary all-star tributes, this one headed up by Jason Aldean, Darius Rucker and Charles Kelley of Lady Antebellum. On one hand, it’s nice to see Allman recognized by an organization so contemporary it also gives out an award for “Social Superstar of the Year,” but on the other it does raise the question of whether CMT might be missing the larger point of what Allman and his band really stood for.

The Allmans were never destined for pop-chart success, “Ramblin’ Man” the glorious exception proving that rule. This band was built for the road and all the toxic hazards that come with it, for virtually endless onstage instrumental exchanges, and indeed songs that could eat up an entire side of an LP (“Mountain Jam,” 1972's Eat a Peach). The first-ballot Rock and Roll Hall of Famers’ career finally wound down after one last show (out of more than 200 at that same venue alone) at NYC’s Beacon Theater in October 2014.

Left in the group’s wake is arguably the greatest single band-family tree in post-WWII U.S. popular music: Gregg’s late older brother Duane, killed in a 1971 motorcycle crash at age 24 but before that a session player for Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett and Eric Clapton’s Derek and the Dominoes; Dickey Betts, Gregg’s intra-band rival who wrote and sang lead on “Ramblin’ Man”; original (and only) drummer Butch Trucks, who passed away in January; and percussionist Jai Johanny Johanson (“Jaimoe”), whose jazz-influenced style was an ideal complement to Trucks’s straight-ahead rock drumming.

Alumni of the Allmans’ second generation, who joined in the years after the original group’s 14-year hiatus ended in 1989, include Warren Haynes, eventual founder of heavy blues-rockers Gov’t Mule; Butch’s nephew Derek Trucks, a member from 1999 to 2014 and later part namesake of the Tedeschi Trucks Band (alongside wife Susan Tedeschi); and bassist Oteil Burbridge, who after the Allmans’ dissolution joined up with Dead & Co, the remnants of America’s other great first-generation jam band — the Grateful Dead.

The Allmans are often credited with helping to coin the genre of Southern rock, although Gregg himself was dubious about the term; he once memorably dismissed it as merely another way of saying “rock rock.” He had reason to be: His band's idiosyncratic sound was a little too hardcore blues and/or jam for the lighter-waving, power-ballad-loving AOR crowds. By far the more important family — both in terms of the brilliance of the pre-plane crash material and the lackluster stuff that followed it — in the development of Southern rock, both sound and stereotype, is the Van Zants of Lynyrd Skynyrd and .38 Special, abetted by Molly Hatchet, Blackfoot and Hank Williams Jr. And bear in mind that ZZ Top, whose greasy and guttural riffs stand as a stark counterpoint to the Allmans’ advanced instrumental algebra, formed the same year (1969) as the Allman Brothers Band.

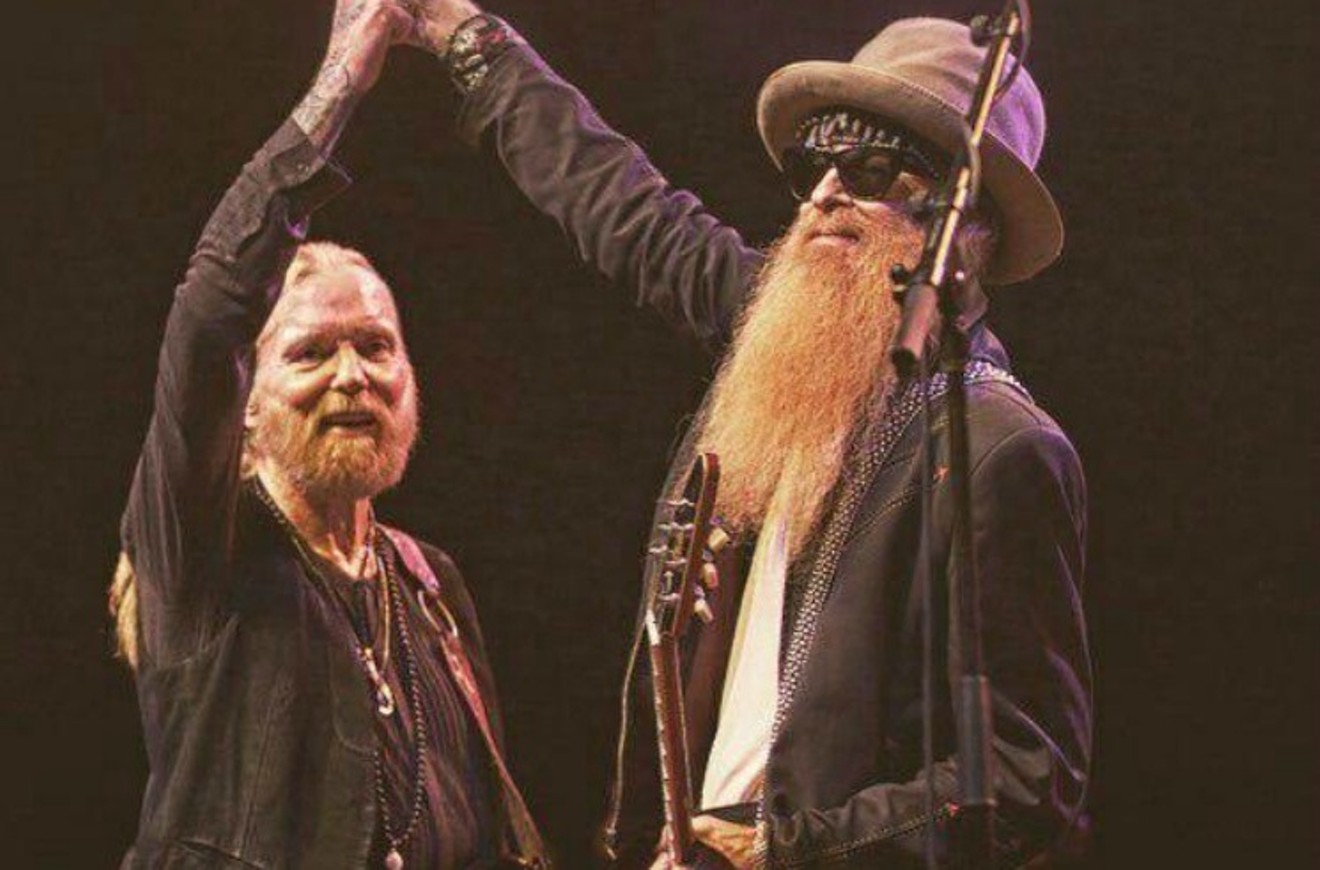

Like Gregg Allman was, Billy Gibbons is a musician’s musician. The difference is that as many of their peers continue to fall by the wayside, ZZ Top just keeps chugging along to the tune of dozens of shows a year, including one September 10 at Sugar Land’s Smart Financial Centre. Gazing proudly up at them is a healthy class of latter-day Southern bands, most prominently Reckless Kelly, Whiskey Myers, Drive-By Truckers, Blackberry Smoke and perhaps Zac Brown and his merry men.

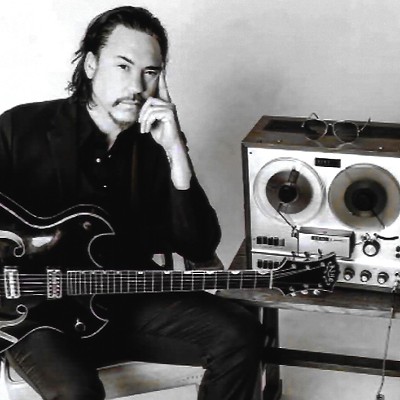

Meanwhile, Gregg Allman’s sticky organ fills have even made their way into the sound of Drugstore Gypsies, a group of rowdy Fort Bend County boys now living in Austin whom Rolling Stone named one of the "10 New Country Artists You Need to Know" last month. Released in March, their self-titled debut LP is undeniably bro-ish, but more in the way that exalts in feckless lyrics like “couch-surfing USA” rather than more loutish behavior; mostly, they sound really, really excited to be playing music.

In that way, if not much else, perhaps they’re not so different from the Allman Brothers Band on Live at Fillmore East. The Gypsies are at least smart enough to put horns that smack of Memphis soul on a few tracks. In fact, when they’re not rocking out a little too heavily — it’s all too easy to visualize many, many AC/DC tattoos on a couple of tracks — the Gypsies could pass for “bad boys” on modern country radio, making them the very type of group with an outside shot at showing up on the CMT Music Awards one day. Shame it’s not tonight.

Drugstore Gypsies perform at Cottonwood (3422 North Shepherd) Saturday, June 10.

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

- Sign out

Gregg Allman and ZZ Top's Billy F. Gibbons onstage in Atlanta, 2016

Photo by Marcel Fernandez/Courtesy of Bob Merlis/M.F.H.

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]

KEEP THE HOUSTON PRESS FREE...

Since we started the Houston Press, it has been defined as the free, independent voice of Houston, and we'd like to keep it that way. With local media under siege, it's more important than ever for us to rally support behind funding our local journalism. You can help by participating in our "I Support" program, allowing us to keep offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food and culture with no paywalls.

Chris Gray has been Music Editor for the Houston Press since 2008. He is the proud father of a Beatles-loving toddler named Oliver.

Contact:

Chris Gray

Trending Music

- Country Rock Thrives with Gene Clark and Flying Burrito Brothers for Record Store Day

- Top 10 Butt-Rock Bands of All Time

- Houston Concert Watch 4/17: Adan Ant, Bad Religion and More

-

Sponsored Content From: [%sponsoredBy%]

[%title%]

Don't Miss Out

SIGN UP for the latest

Music

news, free stuff and more!

Become a member to support the independent voice of Houston

and help keep the future of the Houston Press FREE

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

The Houston Press may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Houston Press, LP. All rights reserved.