This Sunday, Galveston’s Old Quarter Acoustic Cafe will observe its annual Townes Van Zandt memorial wake, which it has done every year since the otherworldly singer and songwriter passed away on January 1, 1997. This year’s edition promises to be especially poignant, not only because it’s the 20th anniversary of Van Zandt’s death, but because Old Quarter owner Wrecks Bell has expanded the rules to include two of Townes’s songwriter brothers in arms who died in 2016: Guy Clark, his best friend and longtime running buddy, who passed away in May at age 74; and their Canadian kindred spirit Leonard Cohen, who died November 7 at 82. Anyone who wishes is welcome to perform up to three songs, provided they were written by Townes, Clark or Cohen. (No covers.)

Thanks to one of his most popular albums, Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas, Van Zandt’s name has long been linked with Houston. Descended from a wealthy Fort Worth family with plenty of Houston connections (his ancestors helped found both Rice University and Humble Oil, later Exxon), Townes lived here for most of the ’60s and discovered his voice as a songwriter while performing at local folk clubs like the Sand Mountain coffeehouse and Jester Lounge. The saga of Van Zandt and his family is admirably told in Robert Earl Hardy’s 2008 biography, No Deeper Blue.

Clark, who grew up in the West Texas oil patch and the Gulf Coast fishing town of Rockport, also spent the better part of his twenties in the Bayou City, roughly, but not continuously, 1963 to late 1970. But because he had lived in Nashville since the early ’70s and many of his best-known songs evoke the Texas of his childhood and adolescence so vividly, information about Clark’s time here has been relatively obscured until just recently. In Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark, published in October by Texas A&M University Press, author Tamara Saviano recounts Clark’s Houston years in depth, providing some much-appreciated insight into how his years living in Montrose helped shape the artist he would soon become.

Here, she writes, Clark listened to recordings of the poet Dylan Thomas, sat in on singalong circles in Hermann Park sponsored by the Houston Folklore Society, and studied intensely whenever legendary Texas bluesmen Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb were performing, often at the same venues he and Van Zandt did. (At various times John Denver, Janis Joplin and Jerry Jeff Walker were also regulars at the Jester, located on Westheimer near Loop 610.) He met and romanced another aspiring folksinger, Susan Spaw; their son Travis was born in December 1966. To pay the bills, he traveled to schools across the South singing traditional folk songs; built and repaired guitars and other instruments, a trade he would continue for the rest of his life; worked in the art departments of Houston TV stations KHOU (Channel 11) and KTRK (Channel 13); and did freelance graphic design for International Artists Records, including the cover of Hopkins’s psychedelia-tinged 1968 LP, Free Form Patterns. Clark hated it, calling it “not my proudest work.”

With all this activity, Clark’s own songwriting skills were long-gestating but finally bore fruit in “Step Inside This House,” which he wrote about the duplex he was living in not far from Sand Mountain on Richmond. The song went unrecorded until Lyle Lovett chose it as the title song for his 1998 album of covers by Texas songwriters he admired. Saviano, a former journalist who became Clark’s publicist and producer of the award-winning 2011 album This One’s For Him: A Tribute to Guy Clark, also describes at length his “immediate” friendship with Van Zandt, with whom he often toured while they were living in Houston, as well as the unusual relationship the two men had with Clark’s future wife Susanna; Susanna and Townes especially, Saviano writes, “shared a private language from the beginning.”

Clark and Susanna’s relationship began under the most tragic circumstances imaginable — he had been seeing her sister, Bunny, largely long-distance until Bunny committed suicide in May 1970 — but their mutual grief helped them form an especially close bond. Susanna followed Clark back to Houston, where she helped convince him it wasn’t exactly an ideal location to become a successful musician, according to a 1994 interview with Susanna that Texas historian Louise O’Connor shared with Saviano: “I said, ‘Well, by God, no producer is going to come knocking on your door in Houston, Texas. You’ve got to do something about it.’”

A few years later, not even out of his teens, an aspiring singer and songwriter from San Antonio spent a few months kicking around some of Clark and Van Zandt’s old Houston haunts before moving to Nashville himself. He was haunted by a mural in Sand Mountain’s back room featuring a handful of alumni from the old Montrose coffeehouse, which was not long for this world: Clark, Townes, Mickey Newbury, Don Sanders and Jerry Jeff Walker. “The place was usually empty when I played, so you could see the mural really, really fucking good,” Steve Earle told Saviano. “It was like Mount Rushmore.”

Walker, meanwhile, moved from Houston to New York and had a huge hit in 1968 with “Mr. Bojangles.” He recorded Clark’s “L.A. Freeway” and “That Old Time Feeling” for his successful 1972 album Jerry Jeff Walker, which helped encourage RCA Records to sign Clark in 1974. Critics immediately praised the emergence of a strong, authentic new voice within country music, even if Clark’s folkish style was considerably out of step with the pop-tinged sound then in vogue on the charts. Despite containing such future Americana/Texas country touchstones as “Desperados Waiting For a Train,” “Texas 1947,” “Rita Ballou” and “Virginia’s Real,” Clark’s two albums found little radio support and RCA declined to renew his contract.

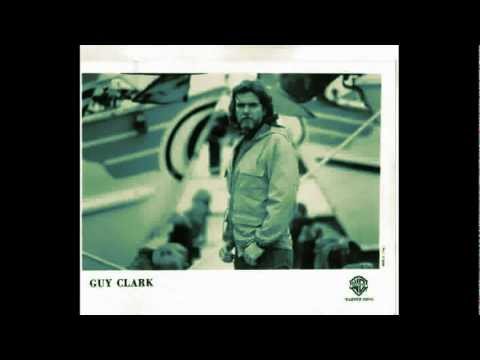

Nevertheless, by then Clark’s reputation had no trouble drawing the interest of Warner Bros.’ Nashville division. In 1978 his first album of three for the label, Guy Clark, scattered the Jimmie Rodgers standard “In the Jailhouse Now” and tunes by his friends Van Zandt and Rodney Crowell among a few Clark wrote himself. One of those was simply titled “Houston Kid,” a memoir of the days a decade earlier when his determination to make everyday ends meet wound up leaving an indelible stamp on his artistic identity.

Now the Houston Kid’s got a new pair of jeans

But he’s got no soap, he got no washing machine

Now the Houston Kid he’s feelin’ tight and he’s mean

And he’s tryin’ to figure out how his pants got cleanWell, he’s doin’ his wash in a tub full of whiskey

Hangin’ his threads on a very thin line

Tryin’ to tell the man in charge of the dryers

What a great job he’s doin’ fakin’ sunshineNow the Houston Kid he seems hard pressed

’Cause he hit the world naked, now he’s headed back dressed

As the Houston Kid, no more and no less

If your dice fit your pocket then your pants pass the testWell, he’s doin’ his wash in a tub full of whiskey

Hangin’ his threads on a very thin line

Tryin’ to tell the man in charge of the dryers

What a great job he’s doin’ fakin’ sunshineNow some say the Houston Kid is bent

But if you’ve got to do your wash

Then you’ve got to pay some rent

So the Houston Kid he just up and he went

And love could buy back the dimes that he’d spentWell, he’s doin’ his wash in a tub full of whiskey

Hangin’ his threads on a very thin line

Tryin’ to tell the man in charge of the dryers

What a great job he’s doin’ fakin’ sunshine

This article appears in Dec 29, 2016 – Jan 4, 2017.