Bob Geldof seems to feel things deeply, sometimes on a rather profound level. You can’t really doubt the sincerity of the guy who harnessed the collective efforts of rock stars, politicians, concert promoters, television executives and power brokers to produce Live Aid, the multinational phenomenon that has been called the most successful charity event ever mounted.

Case in point: A few months prior to the Live Aid concerts in 1985, Geldof met with then Ethiopian President Mengistu Haile Mariam to discuss the famine that was devastating the country. “I walked up to him, I think very sharply,” Geldof recalls, “and I said, ‘I think you’re a c_nt.’” Ken Lennox, a photographer accompanying Geldof on the trip recalls, “It was lighting a fuse. The interpreters stopped interpreting, but even Mengistu knew the ‘f’ word. [Particularly] if you put 14 of them in each paragraph.”

This revelation occurs just over a half hour into “Live Aid: When Rock ‘n’ Roll Took On the World,” a new multipart documentary (available on multiple streaming platforms) produced by CNN and the BBC which celebrates the 40th anniversary of the huge rock and roll fundraiser. An astute viewer might conclude that Geldof was, at that point, only getting started in his quest to raise funds to help famine victims in Africa. Right out of the gate, Geldof had no fucks to give when it came to achieving his goal.

However, in a contemporary interview, Geldof displays what appears to be genuine self-awareness, discussing his discomfort with being portrayed as “Saint Bob” in the media, sometimes in photos where he was surrounded by dozens of starving children. He wrestled with the benefits gleaned from those photo ops versus their performative (some would say manipulative) nature.

This was all before, as they say, shit got real on the Live Aid front, before events were set in motion to stage a worldwide concert broadcast from locales around the globe. In addition to the primary shows in London and Philadelphia, live performances from Australia, the Netherlands, Russia and Austria were included in the televised event. Clearly, this was to be no Jerry Lewis telethon.

As the documentary shows, Geldof only became more insistent (you must!) and profane (fuck off!) in his quest for social and economic justice as plans for the concerts progressed. As Sting remarks, “Bob’s not the kind of guy you can say ‘no’ to. He’s persistent.”

But there were complications beyond rounding up a bunch of rock stars, booking venues and securing television time to broadcast a day’s worth of music to raise desperately needed funds. Initially, the chief roadblock was a political one. Ethiopia was a communist country at the time, and the United Nations, looking at the situation from a Cold War vantage point, was initially reluctant to get behind a relief effort that would benefit people whose government represented an ideological rival to many of its members.

However, once NBC broadcast video from the same television report on the famine that had initially motivated Geldof to act, even virulent anti-communist Ronald Reagan was persuaded to help the Ethiopian citizens. Guided by Peter McPherson, then head of the (recently embattled) United States Agency for International Development, Reagan authorized the shipment of grain from U.S. strategic reserves and granted Ethiopia $50 million in emergency funds.

“Live Aid” contains plenty of video from the era, including newscasts, press conferences and protests. Also included is footage of Geldof touring Ethiopian refugee camps, going toe-to-toe with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and comparing notes with Mother Teresa after they ran into each other at an airport. (Geldof: “I was thrilled to meet this old bird.”)

Several months prior to the Live Aid concerts, two singles were written and recorded to promote the cause of famine relief. The first — “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” — was recorded by British artists (Bono, George Michael, Boy George) in the fall of 1984 and released during the holiday season, garnering massive sales. The bandwagon began to gather momentum when an American contingent of musicians produced “We Are the World” a few months later.

The former recording session had something of a “Hey kids, let’s put on a show” vibe, while the latter was characterized by a studio full of sharp elbows, as dozens of artists vied for prominence. At the time, producer Quincy Jones said that trying to fit so many big names into one song was like “putting a watermelon in a Coke bottle.”

The American production, which took place over one long night following an awards show, was not always a harmonious occasion. After Stevie Wonder’s suggestion to include some African-language lyrics in the song, Waylon Jennings checked out on the proceedings, declaring, “Ain’t no good ol’ boy ever sung Swahili. I think I’m out of here.”

After Stevie Wonder’s suggestion to include some African-language lyrics in the song, Waylon Jennings checked out on the proceedings, declaring, “Ain’t no good ol’ boy ever sung Swahili. I think I’m out of here.”

Only the first episode of the series has been broadcast at this writing, so we must speculate as to what will be included in subsequent installments of “Live Aid.” Certainly, there are plenty of incredible concert performances that might be featured, as a spirit of (mostly) good-natured competition was evident, with no one wanting to be shown up.

Musical highlights included:

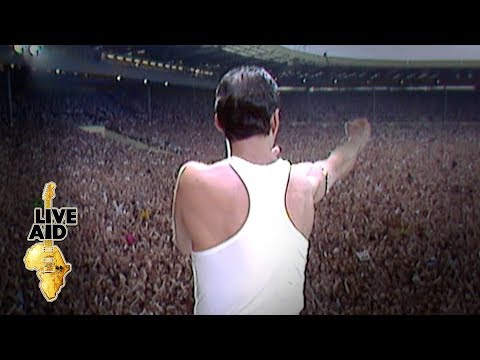

Queen giving what many consider to be the finest performance of the day, led by an incandescent, muscle-shirted Freddie Mercury.

David Bowie delivering a passionate “Heroes,” backed by a hastily assembled but uniformly excellent band.

Eric Clapton tearing it up on “White Room” and “Layla,” reminding everyone that he is a phenomenal guitar player when he wants to be.

Hall and Oates and their band providing the accompaniment for Temptations vets Eddie Kendricks and David Ruffin.

Tom Petty (in some groovy shades) and the Heartbreakers slamming into “Refugee” and injecting a strong dose of rock and roll attitude. During the tune, Petty even flips off someone, albeit with a smile on his face.

Run-D.M.C., the show’s only hip-hop act, energizing the crowd with a brief, supremely confident set, utilizing just “two turntables and a [er, three, actually] microphone.” The guys only did two songs, but “King of Rock” gave a clear glimpse of the future.

Rob Halford (the “Metal God”) and Judas Priest seeing Crosby, Stills and Nash’s “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” and raising them one “Living After Midnight,” kicking the show back into high gear.

With the benefit of 40 years’ worth of hindsight, a viewer might wonder why so much time was allocated to acts like Simple Minds, Nik Kershaw, the Power Station, Thompson Twins and the Hooters. Well, as author S.E. Hinton once said, “That was then, this is now.”

And another thing. Even though Live Aid occurred at the height of his fame, did the world ever really need that much Phil Collins at one time? By my count, he was involved – either singing or drumming – in at least a dozen songs that day. Come on man, give some of the other people a chance!

Also intriguing is the roster of actors chosen to provide onstage introductions. Jack Nicholson? In Ray-Ban shades. Cool. Bette Midler? Not exactly a rocker, but still possessed of and appropriately free-spirited attitude. Cool. Joe Pesci? No discussion. Unassailably cool. And amusing. However. Don Johnson? George Segal? Chevy Chase?

And what about backstage intrigue? Intra-band squabbles? Borderline disastrous reunions? You corral dozens of rock stars with massive egos, and a few conflagrations are bound to occur. Some serious All About Eve action. Will we get to see any of this in future “Live Aid” installments? There were cameras all over the place, so the footage must exist somewhere.

Or will we instead get more of what the first episode of “Live Aid” delivers in abundance: incredibly wealthy musicians in a largely self-congratulatory mood, peppered with occasional displays of (true at the time, but particularly so in retrospect) condescension, cultural ignorance and a general “white savior” complex?

Not sure, but here’s what I do know. After watching the first part of “Live Aid,” I believe that Geldof was and is basically pure of heart, but I am certain that I couldn’t stand to spend more than 10 minutes in the same room with him. And if Bono were thrown into the mix, I might have to scale that time frame down to five minutes.

This article appears in Jan 1 – Dec 31, 2025.