But deeper-diving fans know that around the Umited States, different geographical areas definitely had unique sounds and performers. Mississippi blues doesn’t sound like Chicago blues which differs from Texas blues.

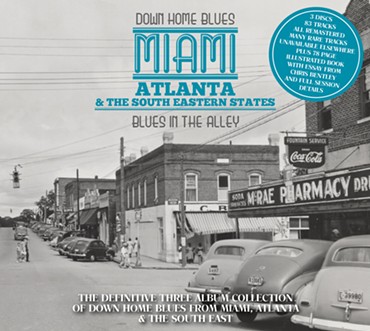

To that end, UK-based reissue label Wienerworld has put out a series of box sets in the Down Home Blues series highlighting lesser-known regional records and performers. The latest is Blues in the Alley: Miami, Atlanta, & the Southeastern States. The 3CD set features 83 remastered tracks with a 78-page booklet featuring historical photos and extensive notation by English blues scholar and author Chris Bentley.

“[Co-compiler] Peter Moody asked me to do it – he called it an essay instead of liner notes – and he wanted 15,000 words. That’s like a small novel!” Bentley says laughing on a Zoom video interview from his UK home. Bentley had previously penned the booklet for another set in the series.

“There was quite a bit of stuff unknown to me, including artists I’d never heard of. But what I really wanted to do was to get one point over. There’s some fantastic music out there that nobody has ever heard. My mission was to make sure that happened, and that people enjoy it.”

He also credits Australian blues researcher Bob Eagle for scouring over documents and public records to piece together the biographies of some of the 29 artists featured like Richard Armstrong, Eddie Hope, Charlie Harding, Earl Hooker, Willie Baker, and Frank Edwards. In some cases, the few songs that appear on Blues in the Alley represent their only recorded output, some not in print since their original, limited releases between 1941-1962.

Bentley’s own journey with the blues began in the mid-1960’s around age 16. That’s when a classmate plopped an LP compilation from the Chicago-based Chess label on the school’s record player. The Chess roster included such giants as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Bo Diddley, and Willie Dixon. And Bentley was instantly hooked.

So too were a number of other English teens with names like Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Eric Burdon, Ray Davies, Peter Green, and Pete Townshend. That all would then take the electric blues music of America, put their own spin on it, and bring it back to these shores to even greater popularity is perhaps the greatest case ever of musical recycling and teacher/student relationships.

Bentley says it’s not hard to understand why English youth of the ‘60s went mad for the blues in a way their American counterparts didn't. “To be frank, the music we had over here was crap! It was dreadful beyond belief! It was 1920’s dance band music. Anodyne pop, horrible stuff,” he laughs.

“The kids wanted something to dance to, something new, and the blues took off. And then [groups] like the Stones and the Kinks hitting America in ’64 and ’65 changed the direction the music was going.”

When American blues performers went over to England to tour, most were shocked not only at the large size and low age of their audiences, but the respect which they received.

“I had the great pleasure of talking to Muddy on a couple of occasions. A lovely man, and he really appreciated the fact that [young people] were listening to him. Those American blues artists were treated like royalty here,” Bentley continues.

“To us, they were an incredible link to the early days of the blues. Muddy played with Robert Johnson and knew him! But he brought this new music to this country as early as 1958. And Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee came over for tours even earlier.”

Back to the box set, Bentley says what makes the Atlanta/Miami sound stand out was that in many ways it was a throwback to the pre-World War II acoustic blues style (though it features both acoustic and electric music). He says that’s due to the dearth of recording avenues in those cities compared to many others.

“There wasn’t a lot of opportunity to record because there was no infrastructure in the South for that – apart from Houston or Nashville. And even if someone wanted to record, they didn’t know where to go. These guys were so dirt poor, they probably didn’t have enough money to even go to the next town,” he says.

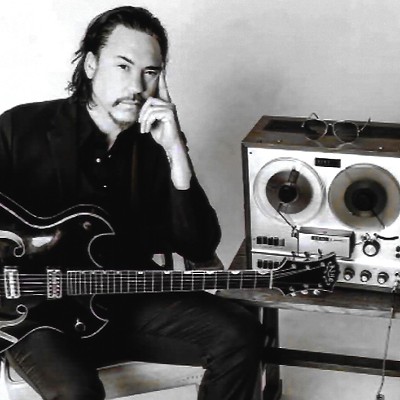

Earl Hooker with his late 1950s Gibson ES-345.

Photo from the Blues Unlimited Archives/Courtesy of Wienerworld

Currently, Bentley is in the early stages of working on a similar lengthy essay about the next compilation in the Down Home Blues series.

The 73-year-old clearly relishes his role as something of a musical detective. He notes that even today many, many decades after they were originally recorded, “new” music by long-dead artists continues to be unearthed in various archives, attics, and storage units around the world.

He mentions three newly-discovered records by Johnny Shaw (who appears on the box set) in just the last couple of months. And that many artists recorded one-off sessions for radio stations during the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s. His personal Holy Grail is finding any copies or evidence of the short promotional films that singer/slide guitarist extraordinaire Elmore James was featured on, performing 2-3 songs in each reel.

And who knows? After all, for decades little was known about bluesman Robert Johnson, and what was often known came wrapped in mystery and folklore (the whole sold-his-soul-to-the-devil-at-the-crossroads bit). But in the past few years, several new books have appeared with previously unknown information (Up Jumped the Devil, Brother Robert).

And after his visage appearing in just two known (and endlessly-reproduced) photographs, and third one has surfaced—and this of a man who died back in 1938 under shrouded circumstances, possibly involving poison and another man’s woman. “There’s a whole industry built around Robert Johnson!” Bentley laughs. “But that’s an entirely different story!”