In 1938, jazz/blues pianist and singer Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe—better known as Jelly Roll Morton—sat down behind the grand piano at the Library of Congress’s Coolidge Auditorium. It was at the invitation of the august institution, and Alan Lomax was ready for him.

Morton was 47 (or 52…accounts vary, just like the spelling of his last name) and considered by many a washed-up dinosaur in music. His abrasive and bragging ways had also made him a few enemies over the years.

Lomax, at 23, was already an experienced folklorist and scion of the famed first family of musical detectives and songcatchers, antecedents of the late former Houston Press music editor John Nova Lomax.

He sat near the ground, machines ready to record anything that Morton played, sang, or reminisced about, often at Lomax’s urging and prodding.

Both men had an agenda, which they kept partially hidden from each other. Morton was looking to jumpstart his career, burnish his reputation with such a prestige project, and cement what he saw as his legacy, history, and contribution—in his eyes—to music.

Lomax, painstakingly trained by his father, John, wanted to get everything in Morton’s head and fingers recorded and documented before its largely oral traditions—and its practitioners—disappeared. And indeed, Morton himself would die in 1941, due to health issues instigated by a violent stabbing attack.

For the course of over nine hours and several sessions, Morton talked about his life, his music, other players, the bawdy and secret nightlife of New Orleans and other cities. He sprinkled in either full takes or excerpts of blues, jazz, ragtime and spirituals. Some were traditional, some adapted, and some he wrote.

But Lomax was after something else as well. He wanted to “catch” versions of tunes with lyrics that no “decent person” would be caught listening to either live or on record. Lyrics that were considered dirty, sexual, racist and/or sexist.

Sometimes, Morton obliged. Other times he demurred or self-censored. And while some of those sessions ended up released on record or transcribed in book form, the purported “worst of the worst” tunes for explicitness would be kept mostly hidden for nearly 50 years until the Library of Congress finally released the complete sessions.

Music journalist Elijah Wald uses those Morton sessions as both the jumping point and the framework for deep and detailed book with a bit of musical detection of his own: Jelly Roll Blues: Censored Songs & Hidden Histories (352 pp., $32, Hachette Books).

In his multi-tentacled tale augmented by more research and digging, Wald reproduces many of the X-rated (or at least a hard R) stanzas, many that even an alternative news publication like the Houston Press would be wary of putting up on screen.

One of the more printable: “Well I ain’t no wine presser, neither no wine presser’s son/But I can press out a little juice for you till the wine presser comes/Can I get you now, baby?”

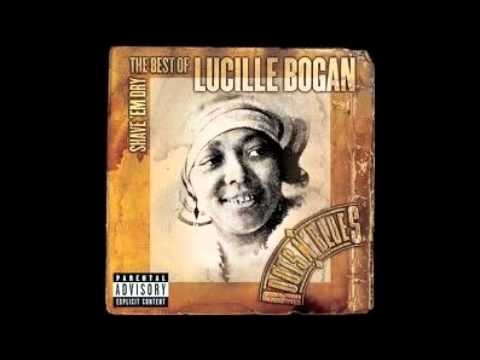

Wald also gives the background on phrases that would pop up again and again in these songs: “Uncle Bud,” “Hog’s-Eye,” “Make Me a Pallet on the Floor,” “Staving Chain” and “Shave ‘Em Dry.” Along with the slight differences between being a “Winding Boy” or a “Winin’ Boy.”

He also tells the, uh, slightly more salacious origins of songs that were later sanitized for mass consumption like “Stagger Lee,” “Frankie and Johnny,” “Wang Dang Doodle” and “House of the Rising Sun.”

Most of these songs would be performed and enjoyed at places of ill-repute, and at night: bars, gambling parlors, “sporting houses” of prostitution, rent parties and illegal dances. Wald also examines the colorful histories of many real-life characters Morton and others encountered in their travels.

These songs were mainly performed by Black musicians (and regular folk) for Black audiences—though Wald also mentions material from white country players. Their song titles included such non-church hymns like “Poontang on the Levee,” “Josie Shook Her Panties Down,” “No More Cock in Texas,” “Fucking in the Goober Patch” and the immortal “Everybody Knows How Maggie Farts.”

Not every song was about sex, though. Others might comment on local news, make good natured fun of people, or tell expansive tales about Blacks outsmarting whites in some manner. There was also plenty of boasting (another precursor to rap) but, as Wald explains, the ladies were just as much out there talking about themselves as the men.

Lyrics, choruses, and music were often adapted and evolved depending in the musician and the setting. And—as Wald notes—it was often a race (or lack thereof) to see who could publish the work first to claim authorship. In typical oral tradition, words were not written down.

And all performers were given extras points for making up lyrics to comment on goings on in the place, individual audience members or neighborhood characters. Wald indeed draws a direct line between things like this and today’s rap battles and more controversial hip hop songs.

Though as was the case with many music genres in those early days, pinpointing exact credit was an impossible task. Jelly Roll Morton could no more seriously claim (as he often did) that he was “The Inventor of Jazz” any more than W.C. Handy could prove he was the “Father of the Blues”—a title he gladly accepted, though.

Jelly Roll Blues is, without a doubt, expertly researched. Wald’s writing does sometimes come across as too academic and textbook-like. And this is certainly not a book aimed at the casual listener or cultural historian. But it’s a very important piece of music journalism and scholarship, proving that even “dirty songs” can have cultural value beyond simply prurient interests.

Oh, and that currently hugely popular rapper-turned-country artist also named Jelly Roll? Ferd was there with the name first. And there’s a lot of suburban moms singing along to “Need a Favor” or “Save Me” who may bit a bit shocked if they knew what his name—and the term—really means…

This article appears in Jan 1 – Dec 31, 2024.