Every so often, a music book comes along that challenges the work which precedes it, creates much discussion (and sometimes consternation), and causes both proponents and detractors to either reexamine or double down on long held beliefs. This book, by folk-blues-rap artist Chris Thomas King, certainly fits that description. Something that may set blues scholarship (and online message boards) on fire.

In a nutshell, the most widely-accepted/promoted “origin story” of the blues involves Africa, the Mississippi Delta, sharecroppers on plantations, and a sometimes depressive music with forefathers like Robert Johnson and Charley Patton.

Here, King argues that blues fermented specifically in Egypt, and was born and nurtured in New Orleans, and birthed by artists like Buddy Bolden, Bunk Johnson, and Jelly Roll Morton. And largely the creation of that city’s Creole populace, often celebratory, and through Morton’s hands in particular.

Those are all names you’d normally find filed under the “Jazz” section in the record store. The genre that is often held up as America’s only true musical invention. But in one of King’s more assertive assertions, there’s no such thing as that.

“Jazz is a misnomer of the blues,” he writes. “The blues was subsequently surpassed, but it remerges under different guises like jazz and swing.” King also dismantles composer/musician W.C. Handy’s self-promotion claims to the title “Father of the Blues.”

King says that Johnson and Patton, rather than originate blues guitar, heard the music from phonographs — especially those of Lonnie Johnson. King crowns the guitarist from New Orleans a much more accurate progenitor.

Let’s be clear. King has more axes to grind throughout this book than a lumberjack’s convention. Some of his statements are as broad-sweeping as those he criticizes. And he sometimes applies 2021 sensibilities and knowledge to people and circumstances of different eras. But his wide-ranging research, attention to detail, and furious flurry of facts are impressive.

One line of thought sure to cause issues is how King — right up in the intro and consistently throughout the narrative — takes to task “White usurpers and appropriators” who have dictated the narrative of blues music and the performers.

Yet in almost the same paragraph, he begrudgingly notes that without white song collectors and academics like John Lomax, Alan Lomax, and Dick Waterman, so much of the music’s history and players would have gone unrecorded, unrecognized and forgotten. Yes, some Black bluesman were taking advantage of by unscrupulous whites, but the same could be said of many other performers, black and white, across genres.

“African Americans of my generation turned their backs on the blues after it was redefined by White usurpers in the 1960s and ‘70s,” the 58-year-old King writes. “We survived, ironically, thanks to White supporters.”

That young Blacks were grooving to the danceable and socially realistic sounds of Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, the Commodores, P-Funk, and Earth, Wind and Fire might also have something to do with that. King is less clear on the line of demarcation between a usurper and supporter. He sees racism, bad intentions, white theft, and the manipulations of the “Blues Mafia”—self-proclaimed arbiters of “blues authenticity”—in every corner.

And it might come as a great surprise to all the Black blues men and women who put out great records for the Alligator label in the ‘90s and about there that King likens their work (with an out of context, older quote from James Baldwin) as “faux Negro entertainment” somehow meant to “assuage [suburban] guilt” and not being connected enough to the ‘hood. Yet in 2021, whites still clearly make up the vast majority of consumers of the blues both on record and in live performances.

The book takes a wholly different turn in the second part when it becomes King’s autobiography. His stories of growing up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana with a blues musician father and club owner (Tabby’s Blues Box), playing with him as a pre-teen, and finding his way musically are interesting and engaging. Surprisingly, a teen King was more into Van Halen, Pink Floyd, and the Sex Pistols than blues artists. When his father Tabby suggested he check out the bluesier Jimi Hendrix material, his path was set.

Houston appears in King’s story via performances at the June 18, 1986 Juneteenth Blues Festival, where he appeared on a bill with John Lee Hooker, Albert Collins, and Johnny Copeland. That night, he sat in at Rockefeller’s with Hooker and Collins and the next day a show in the Third Ward with Collins and Copeland. His time in Austin and gigging at Antone’s is also worthy.

But as King’s career takes off and he starts playing big blues Festival and even tours Europe, he claims the “Blues Mafia” stall his momentum or decry that his music — which incorporated hip hop beats and rap — is not for their tastes. Though it must be noted that King’s melding of rap/hip hop and folk blues may have been some years ahead of its for 1994’s 21st Century Blues…From Da Hood.

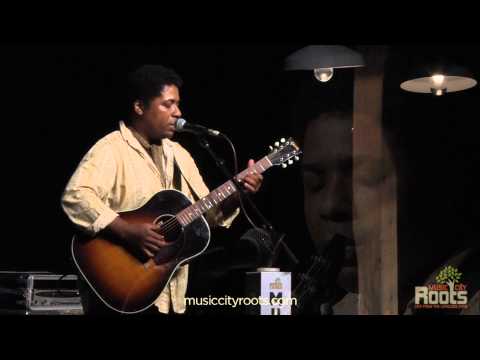

His life takes more ups and downs, personally and professionally, but hits a high note when he joins the cast of the hit film O Brother, Where Art Thou? As bluesman Tommy Johnson (a mash up of real-life unrelated bluesmen Tommy and Robert Johnson), he sings one of the film’s musical highlights, “Hard Time Killing Floor Blues. King later takes part in concerts and tours built around music and acts from the movie, and even attends the Grammy awards where he doesn’t go home empty handed (the film soundtrack won Album of the Year).

Make no mistake, The Blues is a challenging and disruptive book, capable of making the reader nod in agreement on one page and roll their eyes at the next. You may not agree with many of King’s assertions, but you’ll learn plenty of things, and head to YouTube to hear some music.

The Blues: The Authentic Narrative of My Music and Culture

By Chris Thomas King

384 pp.

$30

Chicago Review Press

This article appears in Jan 1 – Dec 31, 2021.