His non-fiction books have dug deep into the history and lore of American criminal gangs across ethnic lines including the Irish (The Westies, Where the Bodies Were Buried), Asians (Born to Kill), Cubans (The Corporation) and of course, Italians (Havana Nocturne). And his The Savage City plumbed the grimy depths of a murder case that spewed racism and corruption in New York City of the 1960s and ‘70s.

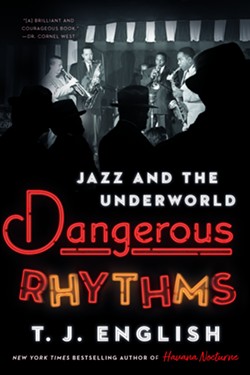

In his latest work, English has been able to combine two of his personal interests with an intertwining tale of a symbiotic relationship played out in smoky clubs, recording studios and the occasional back-alley deal with Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld (400 pp., $29.99, William Morrow, out August 2).

“This is a subject that’s always been in my back pocket. I’m a lover of jazz music and have been since I was a teenager. And one of the great things about becoming an aficionado of jazz is that you can’t help but also get caught up in the cultural history and lore of the music,” English says via Zoom.

“When you bought a jazz record, seeing the liner notes and information, it was like purchasing a jazz encyclopedia. And falling in love with the music was a process of also falling in love with the culture and the stories.”

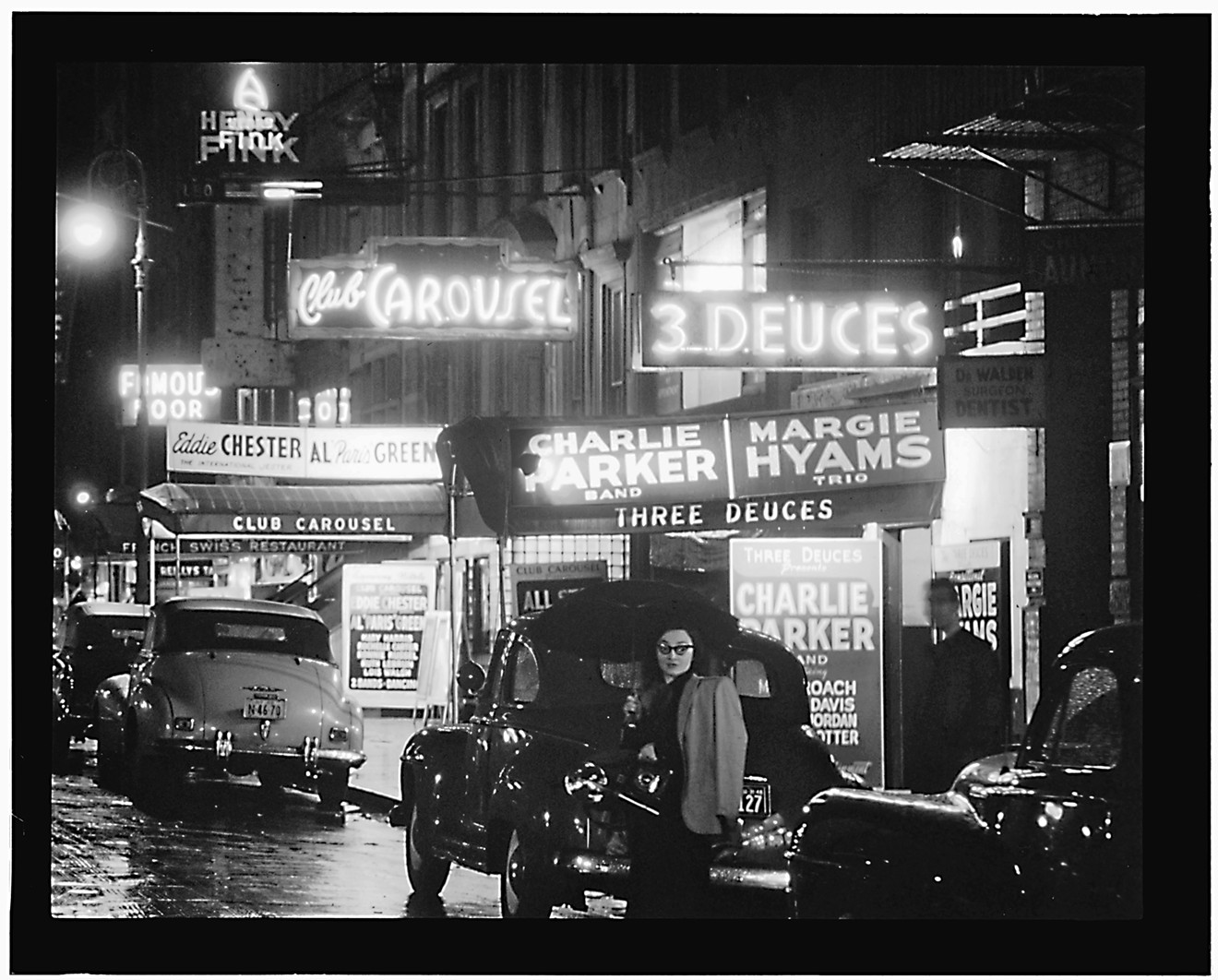

Many of those stories take place during the “golden eras” of big band and bebop, the 1930s-1960s. It was a time when a lot of nightclubs in cities ranging from New York, New Orleans and Kansas City to Las Vegas, Chicago and Los Angeles were owned, run by, or financed by underworld criminals.

“It’s not so much a book about the music of jazz, but the business of jazz and how and why organized crime got their hooks into it so early and laid down a template. It was business model that held for the next 80 years,” English says.

It was an odd relationship, but seemingly one productive for both sides. Great musicians ensured that people ready for a night out of licit-and-illicit fun filled both seats at the clubs and coffers at the back office paying for cover charges, booze, food, cigarettes, hat and coat check, jukeboxes and anything else that was available.

And because the clubs were run by bent nose-types that nobody would mess with, the musicians felt safe, protected and had steady incomes. It was, English says, a “capitalist relationship” at heart.

But in Dangerous Rhythms, English goes deeper than the surface, and has a lot to say about racial relationships, but outwardly intended and inwardly understood.

“The culture at large was at least as violent or more violent toward African-Americans than the club owners,” English says. “I think that the average Black musician had less to fear from a mafioso than a White Cracker on the street or a policeman. That’s why they were open to forging relationships with criminal figures.”

What he sat down to research and write the book, English says something hit him right away. That he wanted to really get into the true nature of the relationship between the underworld figures and the primarily African-American musicians.

So, he says it’s impossible not to see a sort of “plantation”-style relationship between the two groups, even if the setting was a below-the-street nightclub in New York instead of the open cotton fields of Georgia.

“The idea that it would become sort of a plantation relationship is not surprising. The Italians came to America at the time jazz was forming, and it was a quirk of history this coincided,” English says. “The Italians were caught up in the American Dream and consumed with the idea of building a foundation in the new country and getting ahead in the world. This relationship was a consequence of that.”

English adds that an argument could be made that the Italian and Sicilian criminal types had some deeper connection to jazz music as their homeland was closer to Africa that the Irish or Jewish mobsters simply didn’t. Though they had their own impact.

“To unearth these characters like [Louis Armstrong’s manager] Joe Glaser and [club and record label owner] Mo Levy was important, because they were important to the story,” English says.

“Levy was what he was, a bit of a hoodlum and a crooked character. But he was a visionary and progressive lover of the music. What he did for jazz, especially bebop, was unprecedented. And no human being is all good or all bad.”

On the players’ side, English includes stories of Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Fats Waller, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Billie Holiday, Louis Prima, Al Jolson, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne and many others. Employing them are names familiar from Mafia books like Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, Dutch Schultz, Meyer Lansky, Santo Trafficante and Legs Diamond.

Sometimes, the criminal part of the equation crept into the music. English writes of a 1929 incident one night at New York's mobbed up Hotsy Totsy club (co-owned by Diamond). A disagreement between club management and some intoxicated patrons led to an exchange of gunfire that killed seven (with three additional witnesses later "disappearing"). During the melee, a manager told the orchestra to "Play it loud, boys. To drown out the gunfire."

Perhaps the most famous story about the intersection of jazz and organized crime involves the man with one foot in both worlds: Frank Sinatra. In 1942 when his star was starting to rise, the vocalist wanted out of a binding contract to working as part of Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra. The band leader was unmovable and—to be fair—made some unrealistic financial demands to let his dark-haired crooner go.

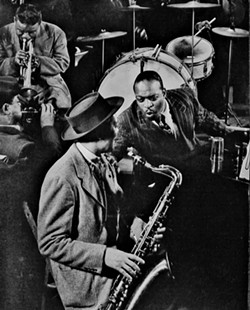

Lester Young and Count Basie played jazz in Kansas City during the Pendergast era.

Photo by Gjon Mili/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

And the story only got bigger with the film version. Putting the muscle on Fontaine's employer was literally the cause of the film's most famous phrase "I'm gonna make him an offer he can't refuse."

For his part, Sinatra always denied that the real or intimated threat of violence toward Dorsey played a part in his sudden contract emancipation. He even angrily confronted Puzo about his fictional story and bellowed about how unfair it was to anyone who’d listen. Scores of Sinatra books have all had slightly varying stories. For his part, English points to several interviews that Dorsey gave in the 1950s that prove the tale’s veracity.

“He described what happened in some detail. He left the names out of it and then when [Mafia enforcer] Willie Moretti died, he started naming names. So, unless you believe that Tommy Dorsey is a flat out liar, that’s the definitive piece of information,” he says.

“The confusion comes from the fact that Sinatra flat out lied about it, and often. Of course, that’s what he said about everything related to the mob and his career. Including his going to Cuba and meeting Lucky Luciano with [a suitcase full of] cash.”

English also feels that facts and archival resources—as opposed to personal accounts that could vary with time—back up a lot of the narrative of Dangerous Rhythms. And his footnotes and bibliography are extensive.

The books isn't out just yet, but English is already hard at work on his next tome, The Last Kilo. It’s the story of the “Cocaine Cowboys” Willie Falcon and Sal Magluta, who pioneered importation of the drug into the U.S., fueling the craze for the white powder in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

Magluta is still in prison, but Falcon is out. English is working directly with Falcon to tell the story via interviews, but says it’s not a biography. And the author has final say on what he writes, includes, or doesn’t include.

“I hope it’s the definitive cocaine book,” he says, before turning his attention back to jazz and the underworld.

“This is a book that was long overdue. I wish it had been written decades ago when some of the musicians were still around,” he sums up. “But during the key era, very few musicians talked about it openly. For obvious reasons! They kept their mouths shut. It was subterranean history for a long time.”

For more on Dangerous Rhythms and T.J. English, visit TJ-English.com