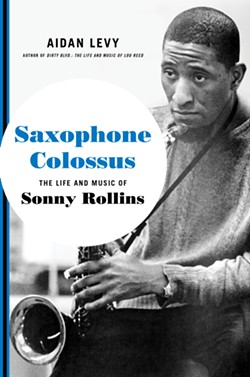

What he’s never had is a true biography that befits his stature. That changes this week with the publication of the doorstop-sized tome named for his best-known work, Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins (784 pp., $35, Hachette Books).

Author Aidan Levy (who has penned bios on Lou Reed and Patti Smith and is a saxophone player himself) spent seven years on the project and conducted more than 200 interviews, including extensive sessions with Rollins himself.

He also had full access to the jazz man’s meticulous archives, organized by Rollins’ late wife Lucille. They now reside in the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Those aspects make the level of detail in the book nothing short of astounding.

“The first album I ever bought with my own money was Saxophone Colossus. I know the expression is ‘I wore out the grooves.’ But I grew up in the CD age. It did skip after a while because I played it so many times!” Aidan Levy says via Zoom. It was an interview he’d done with Rollins for a project with Blue Note Records that led him to embark on writing a full bio.

“I was so inspired by our conversation that I started looking more deeply into his life, music, legacy and career. There were other books, but nothing really comprehensive in terms of a biography,” Levy says. After approaching Sonny himself he “got the green light” to pursue the project.

Growing up in the Sugar Hill area of the Manhattan borough in New York City, young Walter Theodore Rollins took up the saxophone at an early age. Surrounded by clubs and the homes of famous jazz musicians, it wasn’t uncommon to see Lester Young or Duke Ellington on the street.

And he was prolific. In 1956 alone, Sonny Rollins appeared on 10 albums, including key titles on which he was both the leader (Tenor Madness, Saxophone Colossus) and an integral part of (Thelonious Monk’s Brilliant Corners). He explored civil rights via music in 1958’s Freedom Suite.

Throughout the book, there’s much for jazz fans to digest as Rollins crosses paths with a galaxy of legends including Monk, Charlie “Bird” Parker, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Betty Carter, Max Roach and Clifford Brown.

Rollins came up in an era unusually rich with tenor sax players, many also legends (John Coltrane, Dexter Gordon, Ben Webster). But Levy thinks it’s the “bigness” of Rollins’ sound that sets him apart. Not just in terms of volume, but also roundness of tone.

“He developed that from a young age listening to Arnett Cobb and Gene Ammons and Coleman Hawkins. He wanted that big sound, but he brought a sense of articulation that maybe others didn’t always have,” Levy offers.

“There’s a resonance, and Sonny’s sound is really staggering. He’s not slurring the notes and he’s got a playfulness and sense of humor in his music,” the author continues, noting as examples the intro to one of his signature tunes, “St. Thomas,” and his versions of cowboy songs on the Way Out West album.

“Plus, nobody could play as fast as he did. I just found the combination of virtuosity and rhythmic playing captivating. That’s a difficult needle to thread, but he always did it.”

Like a number of his contemporaries, Rollins had a relationship with heroin in an era when many musician acolytes of Charlie Parker mistakenly thought the drug was the key to achieving musical genius. Levy recounts one episode when Parker encountered a very high Rollins and Miles Davis—who was also hooked—at a gig. Bird’s sadly crestfallen face made an impression and impact on the pair more than any intervention could have.

After finally kicking drug and drinking habits, Rollins went the opposite way in terms of his physical condition, maintaining an extremely healthy diet, practicing yoga daily and working out with barbells he would carry even on the road in a suitcase.

Sonny Rollins on the Williamsburg Bridge, October 7, 1961.

Photo by Atsuhiko Kawabata/Courtesy of Hanako Kawabata

Part of the legend of Sonny Rollins includes two “sabbaticals” where he basically dropped out of the music world and social life completely for a couple of years each. The second was in India where he stayed in ashrams and studied with swamis and yogis. But his first and most storied one was in 1960/61 when he would make near-daily sojourns to New York’s Williamsburg Bridge in all kinds of weather, stand outside, and just practice, practice, practice.

Sonny’s “Bridge Years” are part of jazz lore and even pop culture—see the “Bleeding Gums Murphy” character on The Simpsons, loosely based on Sonny. Rollins would later actually voice himself on the show.

But Levy takes a more realistic (and simple) approach. “The lore can sometimes overlook a bit of the story’s nuance. I think his decision to take the sabbatical from touring and performing when he was at the peak of his powers just exemplifies a strength of conviction you rarely see among artists,” he says.

“He wasn’t scared of losing his commercial appeal. He needed to go take time for himself to feel that he was confident in what he was doing, and [achieve] the standard that he set for himself.”

Levy adds that Rollins wanted to work on the “big sound that would blow through the wall.” So, what better place to develop that than outdoors where his horn would be forced to compete with the noise of subway trains, car traffic, boats on the East River and other noises of city cacophony?

“He would leave notes for his wife about when he was going there, and sometimes could be out for 15 or 16 hours,” Levy continues. “It worked for him, and that’s what I wanted to show in the book. It wasn’t a bizarre choice, even though he tried to downplay the way that the industry would exaggerate it.” Levy adds that there is today an actual movement to get the bridge renamed for the jazz great.

Sonny Rollins continued to perform, record, and gig until it became physically impossible. And even non-jazz fans have likely heard him blowing. That’s him playing the memorable solo on the Rolling Stones’ 1981 hit “Waiting on a Friend” (though, as Levy notes, it wasn’t actually recorded in the studio with the band but overdubbed).

Levy says he and Rollins discussed every part of the book and that he himself has seen a copy of both the first draft and final product of Saxophone Colossus. But the author doesn’t expect that his subject read cover to cover.

“I don’t think he wants to read a book about his own life, especially one as detailed as this. It’s the same [reason] he doesn’t like to hear recordings of himself,” Levy offers. His thoughts then go to the famous 1958 photograph A Great Day in Harlem.

In it, photographer Art Kane assembled jazz musicians spanning generations in front of a building at East 126th Street. Of the 57 people featured in the photo, only Sonny Rollins and 93-year-old sax player Benny Golson are still alive.

“I think that Sonny views his [charge] as a responsibility to keep the memories of these great musicians alive,” Levy sums up. “Of course, their music speaks for them. But it’s a blessing to have Sonny still here. And it was a blessing to talk to him about them and himself for the book.”