The connection is told in the fascinating 2021 documentary The Beatles and India (available on DVD & Blu-Ray June 21 from MVD Entertainment). It’s co-directed by Ajoy Bose (based on his book, Across the Universe—The Beatles in India) and Pete Compton.

“I met Ajoy at a forum for the White Album in New Jersey and just approached him about doing this film, and we got along really well,” Compton says via Zoom from his home in the UK. “He had talked to all these people for the book and they also did the film. They all had these unseen photographs of [the Beatles] kind of stuck in albums. So, we had to rush off to the local print show and reproduce them!”

The Beatles were initially exposed to Indian music while filming a scene for the 1965 movie Help! where a group of Indian musicians played in a restaurant. Intrigued by the sounds coming from the sitar and with recommendations from Byrds David Crosby and Roger McGuinn, the Beatles sought out the instruments and its greatest practitioner, Ravi Shankar.

A quick stopover for the band in Delhi the next year further increased their interest, and Shankar offered to teach Harrison how to play—though he forewarned the pop star that it would take some serious dedication and time.

Harrison later followed through but couldn’t shake curious crowds (“When it comes to my holiday, I want to not be a Beatle. I want to be me,” he’s quoted on an uncovered radio interview from the time). “He’s complaining about not getting any peace. He wasn’t being a Fab then!” Compton laughs.

Harrison’s sitar playing would show up on the song “Norwegian Wood,” while Indian sounds and themes would also influence “Blue Jay Way,” “Love You To,” and “Within You Without You.”

The Beatles spiritual journey to India started in 1966 when both Harrison’s wife Pattie Boyd and Paul McCartney saw an advertisement for a UK lecture by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. All but Ringo (who was in the hospital at the time) attended, entranced by the giggling guru who promoted the practice of transcendental meditation.

Partly out of curiosity and partly out of a genuine desire to find something of greater meaning in their lives, they quickly accepted the Maharishi’s invitation to attend a workshop in Bangor, Wales.

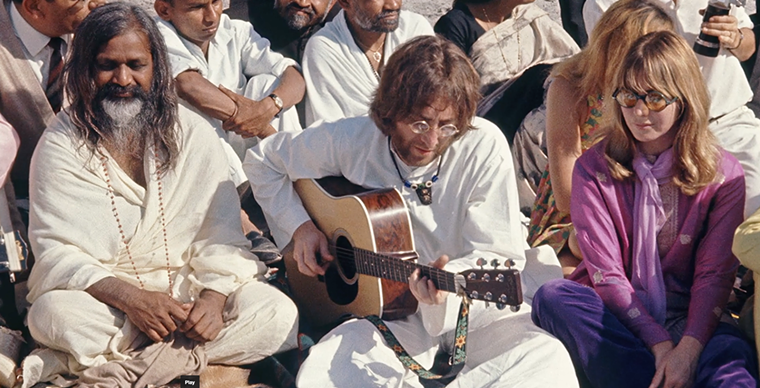

And then in 1968 all four Beatles, their significant others, and a group that included singers Donovan and Mike Love of the Beach Boys and actress Mia Farrow, made the commitment to a longer period of study at the Maharishi’s ashram in Rishikesh. It’s this trip and experience that form most of the screen time at The Beatles and India.

While in Rishikesh, among nature, and away from drugs and (mostly) prying eyes, the Beatles musical creativity exploded, with members composing many tunes that would end up in final form on The Beatles (aka The White Album).

Numbers directly inspired by that time included Lennon’s sarcastic jibe at a tiger hunt that occurred (“The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill”), the practice of chanting mantras (“Across the Universe” which includes the chant “Jai Guru Deva, Om”), and their call to Mia Farrow’s sister Prudence, who became so obsessed that it worried some when she wouldn’t even emerge from her meditations to eat (“Dear Prudence”).

Each Beatle would take away different things from the experience. Ringo and his wife Maureen only stayed a few days, citing homesickness and Ringo’s food allergies as reasons (the drummer famously brought two suitcases: one with clothes and the other cans of baked beans). Paul McCartney stayed for about five weeks leaving when girlfriend Jane Asher had theatrical obligations.

Lennon and Harrison would remain the longest—nearly two full months—but their abrupt departure and public break with the Maharishi (who began somewhat attempting to leverage his connection with the Beatles to his commercial and publicity benefit) was ugly.

A whispering campaign initiated and stoked by band hanger-on “Magic” Alex Madras about purported sexual improprieties against the yogi was all the push that Lennon (whose attention had waned and who wanted to get back to see Yoko Ono) needed. Disillusioned, Lennon would write a song “Maharishi” cataloging his criticisms.

Cooler heads prevailed when it came time to release it, though, and the lyrics and title were refashioned into “Sexy Sadie” on The Beatles album. All four Beatles would in various ways make peace with or speak better about the holy man, with Harrison even apologizing in person years later.

In his opinion, Compton does think the yogi got a raw deal, and that Magic Alex’s version of the story—which he eventually had to give in a deposition for a lawsuit against The New York Times— is “so wrong and untrue, it’s amazing. But he’s a film on his own…this sort of Rasputin figure. And he’s [hanging around] in every photo!”

The Maharishi Mahesh Yogi lectures with the Beatles and their significant others listening.

Screen grab

All give fascinating anecdotes, and Bose and Compton’s cameras catch several of them returning to the ashram today, dilapidated but still a destination for some tourists.

“I’ve been to the ashram twice, and it’s always deserted and uncommercialized. Rishikesh is a hard place to get to, so it’s preserved,” Compton says. “Those scrappy little concrete boxes are still there, and they still retain a lot of magic.”

The one thing that The Beatles and India is missing is actual Beatles music or even cover versions. Compton says the licensing costs from the Apple Corps would have been far too high for such an independent project, nor were they anticipating an official endorsement.

While he notes reaction at film festivals has been very positive over the past year, Compton also doesn’t expect to hear from Paul or Ringo either. “I think they just live for the day and leave it to others to pick through their [pasts],” Compton says. “The Beatles story to me is almost Biblical, just what happened in those 10 years.”

The impact of India on all four Beatles would continue in different ways post-1968. Ringo Starr continues to be a staunch advocate for transcendental meditation, and Paul McCartney and his children visited the Maharishi toward the end of the guru’s life (he passed in 2008 at the age of 90).

John Lennon says in the film “The happiest time of my life, one of the happiest times, was in India. It was such a groove, such a pure thing. Everything is slightly more in perspective.”

Of course, it was George Harrison who continued the closest and lifelong connection to Indian music, Hinduism, and deep friendship with Ravi Shankar (whose suggestion to Harrison about combatting famine directly resulted in The Concert for Bangladesh).

“George is the mystical Beatle. He was searching for [a reason] why he was chosen to be famous worldwide. He was going to be an apprentice electrician before joined the group!” Compton says.

“He was the kid in the band, and then he became the wise one. Something we couldn’t put in the film was how many times he went to India for the rest of his life. And of course, his [ashes] were scattered in the Ganges River.”

Finally, when asked what he learned most about the Beatles making the documentary, Compton’s answer is quick.

“It’s their kindness. When they were in India, they didn’t have on any airs and treated everyone on the same level. And people who actually met them said they were always very polite,” Compton sums up. “There was no superstar behavior. Everyone was on the level.”