Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

- Sign out

Sol LeWitt Work Is Last Exhibit at Rice Gallery Before the Big Move

Kelly Klaasmeyer March 7, 2017 8:00AM

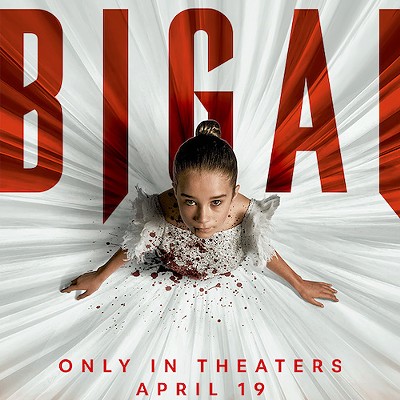

Sol LeWitt, Glossy and Flat Black Squares (Wall Drawing #813), 1997

Photo by Nash Baker

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]

After more than 20 years of stunning, nationally and internationally acclaimed installations, Rice Gallery is being closed — making way for a Rice University welcome center.

For the final show, the walls have been painted black, as if the gallery is shrouded in mourning. “Sol LeWitt: Glossy and Flat Black Squares” is a reinstallation of the conceptual art pioneer’s work created specifically for Rice Gallery and shown in 1997 at the request of the then recently hired gallery director, Kimberly Davenport.

At the time, Davenport had made the decision to have the gallery focus exclusively on site-specific installation art. Part of the initial impetus was budgetary. In the early days, the exhibition budget was about ten grand. Davenport realized you could bring an artist in and have that person make work on site for less than the cost of shipping and insuring existing work. And, she says, “I thought it wouldn’t just be taking things out of a crate and hanging them on the wall. People would see the process; they could press their faces up to the glass.”

LeWitt created his wall drawings through a series of instructions that could be executed by others. (His early works used drawing media but he moved to paint in later years, still referring to them as drawings.) They were temporary, and the same drawing could be installed in multiple places at the same time. The process of art being made by someone else through written instructions may seem clinical, but the results are not.

In the Rice Gallery installation, black paint with either a flat or a gloss finish is brushed in rectangles and squares on the gallery’s three 16-foot-high sheetrock walls. On the left wall is a rectangle with one-half gloss black, one-half flat black. The back wall has a square diagonally divided into flat and gloss black. On the left are two squares side by side, one gloss and the other flat.

These vast planes of blackness overwhelm the viewer. They are all at a much-larger-than-human scale, and when you stand in front of them, you are encompassed by their darkness.

The gloss paint has a hazy reflectivity that gives you a muted image of yourself as you move through the gallery, and disappears when you pass a section of flat black paint, which traps rather than reflects light, creating a kind of dark void. Each has a gorgeous smooth surface, subtly furred with the brush strokes of coats and coats of paint.

According to Rice Gallery preparator David Krueger, an artist himself, the installation of the wall drawing took six weeks, with ten people working on it off and on. The powerful physical presence of the work, its sense of richness and solidity, owes much to the laborious process behind its creation. You can’t just roll on a bucket of Behr and get the same effect.

Before anything, the walls had to be prepped to create a marble-smooth surface. The gallery has presented more than 70 installations throughout its history, and all that painting and repainting gunks up the walls. Krueger says that eight years ago or so, they had to cut a hole in the sheetrock of the gallery walls. The chunk of wall taken out had multicolored layers of paint a half inch thick, like some sort of geologic strata.

“If you went down a half inch of paint, you would find the original LeWitt installation from 1997,” says Krueger.

Prepping the approximately 2,000 square feet of gallery walls required coats and coats of sheetrock mud, much sanding, more coats of primer and paint. Finally, the squares and rectangles of black were created by brushing on multiple coats of black paint, thinned with matte or gloss medium. The layer upon layer of pigment imparts physical depth to the color.

“Glossy and Flat Black Squares” is a quiet and elegant ending for a space that has hosted such a dynamic range of work. Rice Gallery is/was the only university art gallery in the nation dedicated solely to installation art. Gallery director Davenport hunted down young artists and gave them their first big chance to do something amazing. Tara Donovan’s “Haze,” her 2003 installation at Rice Gallery, created an ephemeral, cloud-like mass using the cheap disposable material of plastic drinking straws — two million of them stacked against the wall. It was a stunning achievement that led the way to a major installation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2007 and a MacArthur fellowship (“genius” grant) in 2008.

Meanwhile, “Shape of Space,” Alyson Shotz’s 2004 Rice Gallery installation with more than 18,000 magnifying plastic Fresnel lenses clustered like fish scales, was purchased by the Guggenheim for its permanent collection. (It was a part of the Summer Window series, which was begun to keep the gallery active when the space was closed for the summer, through the commissioning of work for the window wall of the gallery.)

Rice Gallery has challenged older blue-chip artists such as Joel Shapiro by giving them the chance to work in a new way. For his 2012 “Untitled” installation, it was as if the septuagenarian Shapiro had blown apart the components of one of his gravity-bound sculptures; colored planks and rectangles were suspended in the air, seemingly caught in mid-flight. Shapiro went on to do more suspended works in a 2016 show at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas.

Davenport has also brought in projects from people working in the design and architectural fields. In the 2006 “Rip Curl Canyon,” the architects of Ball-Nogues Studio created a phenomenal undulating landscape of cardboard. Then there was the botanical exuberance of the 2005 “Eminent Domain” installation of designers White Webb.

Rice Gallery curator Joshua Fischer, who has worked with Davenport since 2007, says, “Kim has a knack for finding people that are not an obvious fit for installation art and seeing something in their work that translates to a larger scale and creates a kind of world or environment that is engaging.”

After the gallery closes, Davenport and Krueger will move over to the newly opened Moody Center for the Arts, a $30 million, 50,000-square-foot building where Davenport will be chief curator. Fischer will relocate to Boston, where his wife does medical regulatory work. The Moody Center has a focus on collaboration and is touted as “an experimental platform for creating and presenting works in all disciplines.”

It will be interesting to see what Davenport will accomplish at the new venue — the Moody Center will offer more space and, one assumes, more resources, allowing her to expand on the kinds of interdisciplinary outreach Rice Gallery has been pursuing for the past 20 years.

While students from all areas have been involved in executing Rice Gallery’s often massively labor-intensive installations, the gallery has collaborated with the School of Architecture on numerous occasions. In 2002, department students and professors realized “Bamboo Roof,” designed by noted architect Shigeru Ban. In 2015, Rice architecture students, Spanish architect and Rice professor Jesús Vassallo, and Tokyo-based architecture studio Atelier Bow-Wow produced “Shotgun,” a riff on the vernacular structure.

For the New Art/New Music series, students from the Shepherd School of Music have selected or composed music in response to the installations and performed it in the space. The Words and Art series, organized by Mary Wemple, allows writers to create and present work in response to the gallery installations. And workshops and professor lectures related to the installations have been given on everything from acoustics to soil composition to physics to flora. Videos by Walley Films documenting the installations have been featured by the likes of National Geographic and The Atlantic.

There does, however, seem to be a lack of clarity surrounding the end of Rice Gallery. An email from B.J. Almond, senior director of news and media relations, stated, “University leaders made the decision to relocate the Rice Gallery to the Moody Center.” But how is a gallery “relocated” if there is no designated space for it and the name will no longer be used? A statement from Alison Weaver, the Suzanne Deal Booth Executive Director of the Moody Center for the Arts, explains, “We are going to continue the tradition of site-specific installations, but allow the artist to select where in the building they would like to intervene. We have a variety of fantastic indoor and outdoor spaces for original art work.”

Weaver is no doubt right, but one still wonders why university leaders wouldn’t allow a dedicated art space and a cross-disciplinary space to exist simultaneously on campus.

A thoughtful article in the Rice Thresher, “A Eulogy for Rice Gallery,” by Lenna Mendoza, laid out a student perspective, describing the gallery’s prominent location in a building not exclusively dedicated to art. “Faculty and students who would not have ever visited the gallery at the very least walked by, at the best were pulled in. Simply put, the gallery was hard to ignore, and at a university where attention to and respect for the arts has been undeniably lacking, the location of the gallery was essential…The Moody Center will offer more arts space centralized into a single building tucked away at the far end of campus, which will likely prevent the attention drawing effect the Rice Gallery excelled at.”

Perhaps Sewell Hall was too dangerous a location, making visual art too, well, visible at an institution with a decided “left brain über alles” bent? Is a banal “welcome center” preferable to the campus’s looking “arty” at first glance?

In the end, Rice University is a very Houston institution. And Houston has always enthusiastically bulldozed its history to make way for the new and improved. While gaining a gleaming new multidisciplinary art space, Rice is razing an established international-caliber destination for contemporary art.

In the meantime, “Glossy and Flat Black Squares” is up until May 14. Standing in the space, surrounded by the subtly shifting blackness, is strangely moving. For me, it conjured the sort of secular spirituality I always think I ought to feel when I visit the Rothko Chapel but never do.

If we have to say good-bye, I can’t think of a better way.

Sol LeWitt: Glossy and Flat Black Squares

Through May 14. Rice Gallery, 6100 Main, 352 Sewall Hall, 713-348-6069.

KEEP THE HOUSTON PRESS FREE...

Since we started the Houston Press, it has been defined as the free, independent voice of Houston, and we'd like to keep it that way. With local media under siege, it's more important than ever for us to rally support behind funding our local journalism. You can help by participating in our "I Support" program, allowing us to keep offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food and culture with no paywalls.

Kelly Klaasmeyer

Contact:

Kelly Klaasmeyer

Trending Arts & Culture

- Fallout Successfully Makes the Transition From Video Game to Streaming Show

- The 10 Best And Most Controversial Hustler Magazine Covers Ever (NSFW)

- Love is in the Alley's Charming Production of Brontë Classic Jane Eyre

-

Sponsored Content From: [%sponsoredBy%]

[%title%]

Don't Miss Out

SIGN UP for the latest

arts & culture

news, free stuff and more!

Become a member to support the independent voice of Houston

and help keep the future of the Houston Press FREE

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

The Houston Press may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Houston Press, LP. All rights reserved.