A palpable, intrinsic loneliness and a sense of being disconnected from the world is inherent in Emily Dickinson’s succinct but poignantly profound epistolary poem entitled “This is My Letter to the World“:

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me—

The simple News that Nature told—

With tender MajestyHer Message is committed 5

To Hands I cannot see—

For love of Her—Sweet—countrymen—

Judge tenderly—of Me

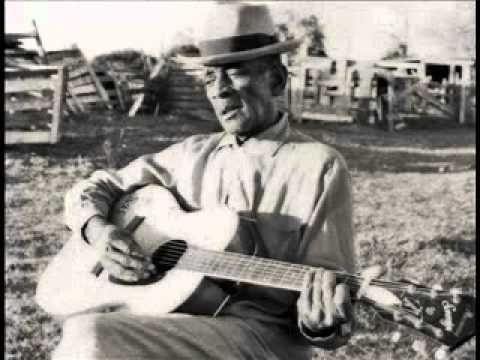

Dickinson’s eight-line poem expresses a kind of unrequited love for a world that only bore witness, in the purest sense, to her virtuosic poetic genius posthumously. Musicologist, researcher and blues scholar nonpareil Mack McCormick, who passed away at age 85 in Houston on November 18, once spoke of a connection to Dickinson’s life story, her poetic ouevre and this poem in particular. To Texas Monthly writer Michael Hall, McCormick described Dickinson as “so inspiring” and offered this assessment of her poem: “All I have to do is go to one of her poems for hope,” he said. ‘”This Is My Letter to the World’ is the most heartbreaking poem, and the closest to my own lonely feeling sometimes.”

McCormick was never really alone, however. He was inspired by the lore, personalities and spirits of numerous musicians, and preserved their legacies through his research, which is compiled in his vast mythic archive aptly named “the Monster,” which had been divided between homes in Houston and the mountains of Mexico. Like the Lomax family members who were involved in recording and documenting the blues of the Mississippi Delta and Texas, as well as the music of Haiti with the guidance of author Zora Neale Hurston (long before film director Maya Deren’s Divine Horsemen era), McCormick was a folklorist and ethnomusicologist with a heart.

He was deeply invested not so much in the payoff of his field research and scholarly pursuits, but in developing, preserving and protecting the histories of important blues musicians. These men included proto-blues guitarist Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas; Third Ward’s Sam “Lightnin'” Hopkins; Navasota blues-guitar legend Mance Lipscomb; Coutchman, Texas native and blues legend Blind Lemon Jefferson; the legendary preacher and singer-guitarist Blind Willie Johnson; and Lead Belly, who was essentially discovered by Alan Lomax and John Avery Lomax, both of whom recorded his singing and guitar playing while he was incarcerated at Louisiana’s infamous Angola Penitentiary in 1933.

McCormick became a legend of sorts in the areas of field and scholarly research over the years, as well as his groundbreaking unpublished research — and pulling the plug on Bob Dylan. That incident occurred at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival during the singer’s historic and genre-defying electric set, which went past the allotted time and and spilled into a block of time reserved for a group of ex-convict musicians assembled by McCormick:

“I was trying to tell Dylan, ‘We need the stage!’ He continued to ignore me,” McCormick told Texas Monthly. “So I went over to the junction box and pulled out the cords. Then he listened.”

Despite that incident, McCormick was perhaps best known as being the supersleuth who possibly solved the deep, murky mystery surrounding the death of iconic blues guitarist Robert Johnson, which ranks second behind Johnson’s mythic “Crossroads” legend in terms of its sociocultural and historical significance within the context of the blues; these days, perhaps it almost trumps even that tale. In his travels through Mississippi, McCormick would ask people questions about Johnson while riding a bus that doubled as a store named the Rolling Store. At some point, though, McCormick abandoned his Johnson biographical project, entitled Biography of a Phantom, but hopefully his painstaking research will come to light someday.

McCormick was a retiring figure who literally helped hundreds of people over the years, some of whom could probably be classified as ‘vultures’ who directly benefited from his vast knowledge and archives. His diligent work inspired and has had an impact on younger black roots music and blues musicians working today — and on a number of white musicians who have covered Texas blues musicians’ works, from either a blues or rock and roll perspective. Dom Flemons has often done covers of musicians researched by McCormick, and is known for his quills and guitar cover renditions of Henry Thomas’s iconic song “Fishing Blues.” It was McCormick who literally retraced Thomas’s steps and wrote about the legendary guitarist. Flemons, who has worked as a member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops and as a solo artist, obviously benefited in some way from McCormick’s work regarding Thomas — as have countless other people.

Perhaps one of McCormick’s lesser-known accomplishments involved the documenting and recording of “Barrelhouse” Texas piano players. This unique blues style, perhaps in part descended from ragtime, developed in barrelhouses where whiskey was served directly from barrels. McCormick recorded a pianist by the name of Robert Shaw in Austin and released Shaw’s Texas Barrelhouse Piano album on McCormick’s short-lived Almanac label. Shaw, like a pianist known by the moniker Grey Ghost (Roosevelt Williams), was one of the best-known Texas players working in the style. Shaw owned a grocery store for years on Austin’s then predominantly black East Side called the Stop and Swat.

Shaw also played piano in Houston’s Fourth Ward for years before, as McCormick’s album liner notes state: “The juke box and the law killed off the barrelhouse. Spirits and exposure killed off the piano players.” Like the great Peg Leg Will, Shaw was one of 212 “Santa Fe” barrelhouse piano players in Houston’s Fourth Ward (a number estimated by McCormick). On the side opposite the Shaw album cover near the bottom edge, McCormick placed a quote from a poem that appeared in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass entitled “By Blue Ontario’s Shore.” It reads, “Who are you indeed who would talk or sing to America?/ Have you studied out the land, its idioms and men?” The second line of the two seems to presciently describe McCormick’s life passion, which began in a professional sense when he assisted native Texan and New Orleans-based jazz discographer Orin Blackstone with Blackstone’s Index to Jazz: Jazz Recordings, 1917-1944, which was first published in 1948. McCormick also helped coin the term ‘Zydeco.’

A November 2008 profile of McCormick by the Houston Press, written by John Nova Lomax, revealed McCormick to be a cocktail-loving humorous character full of incredible anecdotes about encounters with Tennessee Williams and Frank Sinatra, who would later befriend McCormick’s versatile bluesman friend and discovery Mance Lipscomb — who once serenaded Sinatra and Mia Farrow on Sinatra’s yacht. McCormick was also a playwright who had written at least eight plays, including works about Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. He also worked as a correspondent for Down Beat magazine, and also recorded, compiled and wrote the liner notes of a folk album released in 1960 called The Unexpurgated Folk Songs of Men. McCormick was also an interesting character on his own who sometimes flirted with trouble. He mentioned his encounters with Houston cops to Lomax:

Years ago, I went crazy I got in the habit of going down to the Dunkin Donuts on Long Point where the cops drink their coffee and I would get in arguments with them. I used to bring this big can of spray paint and tell the cops that they needed to paint their bumpers with their car number in huge numbers so people would know who they were when and if the cops were misbehaving.

McCormick had a number of other interesting ideas and theories. “Old people live to the end of their money,” he told Lomax. “I lost about $40,000 on the markets last week, so I figure that’s about three years gone for me.” He also took a tabula rasa approach to research, emphasizing the importance of going into the field with no agenda or angle in an attempt to obtain information in the purest, most honest way possible. His approach, as he told Hall in that Texas Monthly story — entitled “Mack McCormick Still Has The Blues” — was simple:

The way to do field research is always from a standpoint of ignorance. Don’t decide beforehand what you want to find — leave your preconceptions out of it. I’ve always found it exhilarating to knock on doors. I’d stop in a town, knock on someone’s door, and say, ‘I’m lost.’ Or people would be playing dominoes and I’d say, ‘Can I watch?’ Get friendly with people. After awhile, ask a bunch of questions at once, get them agitated, sit back, and they start answering them.

When McCormick passed away last month, he left behind a daughter, Susannah McCormick Nix; a son-in-law, David Nix; and a college-bound granddaughter, Emma. His daughter, certainly grieving after the loss of her only surviving parent, carried on during the Thanksgiving holiday by baking delicious pies. And perhaps he knew he wasn’t anywhere near as lonely as Dickinson was when she wrote “This is My Letter to the World.” Speaking to Hall, McCormick offered words of wisdom concerning the interconnectedness of human beings. “Each of us are connected by an infinite number of threads,” he said.

This article appears in Holiday Guide 2015.