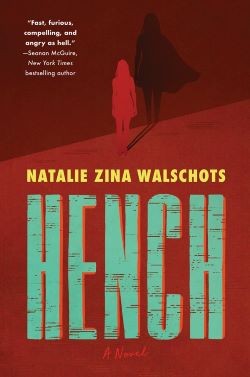

Natalie Zina Walschots’ debut novel Hench is both a razor-sharp deconstruction of the superhero genre as well as the best example of prose writing on the subject since Austin Grossman’s Soon I Will Be Invincible. Even while she’s pulling off that unlikely trick with deftness and wit, she also managed to turn out an amazing work of laborpunk that felt more empowering than being gifted with a magic space ring.

The hero of the story is Anna. She’s your typical temp office worker except for one wrinkle: the agency that represents her recruits for supervillains. I’ve covered this before, but there must be a huge support network for the various supervillains of the world in order to build lairs, run communications, and do other necessary evils. Someone has to file the time sheets, and Anna is that someone for whatever masked megalomaniac is doing well for themselves.

That is until she is caught in a violent rescue by a superhero where she is accidentally disabled. The in-universe equivalent to Superman, Supercollider, ends up pulverizing her leg and leaving her with months of physical therapy just to walk again. She can’t work, and so she begins to spend her free time adding up the total cost of superheroics in terms of hours of life lost because of injuries and property damage. Her research reveals a terrifying truth: superheroes just aren’t worth it. Their actions, no matter how flashy, cause more damage than they prevent when looked at from a sociological scale.

Dependent on a cane, out of work, and hounded and harassed by the giant superhero hype machine, Anna turns her spreadsheet magic into a thriving blog that eventually puts her at the right hand of the world’s foremost supervillain. From there she launches a Tyler Durden-style campaign of trolling incidences that aim for the end of the superhero as an institution.

There are two themes in Hench that make it so compelling. The first is laborpunk aspect. Anna is a very regular person who just wants to make ends meet. Late stage capitalism has failed her, and she is utterly bereft of optimistic ideology at the start of the book. She has to eat, and supervillains are hiring. Anna is every one of us that has pushed down our principles to pay the rent in a world that increasingly does not play fair. Her willingness to aid villains is as much about her broken faith in the system as it is an act of necessity. She, like so many of us, has marketable skills and a supreme work ethic, yet remains nearly in poverty. That’s a point at which good and evil, embodied in the gaudy metahumans, breaks down. All it takes is one employer truly believing in her and respecting her for her to become the sort of power that even supermen fear. Siri, play “My Shot.”

The second theme is justice. Is it just for a superhero to save a mayor’s son at the cost of a lifetime of pain and disability of a few people just trying to scrape by in a system that refuses to care for them? Is it just to call a person a supervillain without knowing his or her entire story? How much pain, betrayal, and sacrifice is justified for the greater good, and who decides what the greater good even is?

Underneath Walschots' prose is a strangely optimistic view that the world should simply be fairer even if it is less flashy than a man who can fly. What saves the book from naivete is the iron she puts in Anna’s spine. I wouldn’t call Hench a horror novel by any stretch of the imagination, but the final showdown involves a level of body horror that would make Clive Barker squirm. Was it just for Anna to do this horrible thing she ends up being the architect of? That’s the uncomfortable question Hench leaves a reader with. In the end, is any force the right thing to do no matter how righteous?

Walschots is a marvel, having brought new life into the superhero genre right as the lack of summer blockbusters gives us a little time to pause and consider the medium. Her work has far more heart than something like The Boys and is far more hopeful than Watchmen. Hench is a wonderful allegory for the average person trying to survive in a world where even benevolent powers with good intentions often cause us irreparable harm, and it shows how we can bring that world to its knees with the right amount of initiative and a copy of MS Excel. If that’s not the message we need right now, I don’t know what is.

Hench is available on September 22.

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

- Sign out

Natalie Zina Walschots

Photo by Max Lander

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

,{

"name": "RevContent - In Article",

"component": "12527128",

"insertPoint": "3/5",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

}

]

KEEP THE HOUSTON PRESS FREE...

Since we started the Houston Press, it has been defined as the free, independent voice of Houston, and we'd like to keep it that way. With local media under siege, it's more important than ever for us to rally support behind funding our local journalism. You can help by participating in our "I Support" program, allowing us to keep offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food and culture with no paywalls.

Jef Rouner (not cis, he/him) is a contributing writer who covers politics, pop culture, social justice, video games, and online behavior. He is often a professional annoyance to the ignorant and hurtful.

Contact:

Jef Rouner

Trending Arts & Culture

- The Hills Are Alive at the Wortham With HGO's The Sound of Music

- The 10 Best And Most Controversial Hustler Magazine Covers Ever (NSFW)

- Top 5 Sickest Stephen King Sex Scenes (NSFW)

-

Sponsored Content From: [%sponsoredBy%]

[%title%]

Don't Miss Out

SIGN UP for the latest

arts & culture

news, free stuff and more!

Become a member to support the independent voice of Houston

and help keep the future of the Houston Press FREE

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

The Houston Press may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Houston Press, LP. All rights reserved.