By now, there have been more gallons of ink spilled in chronicling, analyzing and Monday Morning Quarterbacking the Civil War than blood spilled on all of its battlefields. Yet the period remains catnip to scholars and amateur historians for its deep-set meanings and motivations that still resonate today.

But noted historian and Pulitzer Prize winner Alan Taylor has done something different with his latest doorstop tome, American Civil Wars: A Continental History 1850-1873 (560 pp., $39.99, W.W. Norton). And that’s because the takes the “American”—as in North American—definition wider.

So, while the bulk of the book is a compact social, political and military look at the United States before, after, and during the Civil War, Taylor also includes the struggles and identity crises of our neighbors to the North in Canada and South in Mexico, who each faced their own “civil” battles.

For Canada, it was their French vs. English territories and people, and the bid to establish transcontinental relations and trade. For Mexico, it was liberals vs. imperialists—plus throw in an attempted overtaking and rule by France by Napoleon. Napoleon III, that is.

And both countries were more than concerned the more powerful meat it the North American sandwich would eventually come to overtake or annex them—just as the United States was pushing West and subjugating or destroying the Native Americans. Manifest destiny, indeed.

We’re taught that the U.S. Civil War was fought to “preserve the Union” of the United States. But the truth is, a Taylor notes, the country was more made up of regional and state powers and goals with little uniting any cohesive drive.

“Here was the tragic paradox: Americans needed a Union to keep their peace, but by clashing over the meaning of Union, they invited a bloody division,” he writes.

And indeed, United States citizens were at boiling point with each other over politics, religion, gender roles, and racial equity and rights when Blacks were considered third class citizens at best, property to be used at worst. Some of that sound familiar?

Taylor notes how quickly things could turn deadly in the absence of actual facts. When a number of businesses caught on fire in Dallas, Texas during the summer of 1860, wild rumors and innuendo quickly spread about its source.

That white anti-slavery Abolitionists had promised local Blacks freedom and rewards if they committed arson. That the city’s water supply had been laced with strychnine so as to killed swaths of white men, leaving only Blacks as potential husbands for their daughters, the “ultimate nightmare of Southern white men.”

Purported arsonists were rounded up and executed—including a Methodist minister from Missouri who had simply been seen talking with a group of slaves. Bounty hunters found him and Missouri and brought him back to Fort Worth for deadly justice.

But when it was discovered that the true source of the fire was the spontaneous combustion of the then newly invented phosphorous matches on store shelves that ignited in the intense summer Texas heat, the alleged perpetrators had already been killed.

Taylor offers a fairly concise summation of the Civil War, using specifics battles and their outcomes as turning points. His President Abraham Lincoln is also painted as conflicted. His main cause was to preserve the Union at all costs, saying whether that meant he must free all the slaves or none of them.

Despite how Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation are viewed and celebrated in 2024, Lincoln initially pushed for the containment of slavery—not its eradication. And even the Proclamation exempted a number of states, including Tennessee and Louisiana from its provisions. It also, conveniently, allowed for the recruitment of Black soldiers to the Union cause, increasing their ranks and terrifying Confederates.

And just because the slaves were “freed,” doesn’t mean they were free. Sure, they were emancipated, but put out with no money, land and little provisions, they were still subject to beatings, robbery, torture and imprisonment—be it by vigilante groups or with the winking eye of law enforcement, especially in the South.

Taylor includes tales of the destruction and power of often ad hoc groups with colorful names like Border Ruffians, Filibusters, Jayhawks, and Copperheads. They could plead the case for their cause in the public square in the afternoon and take more violent approaches at night.

The issue of slavery, though, is the one that dominates American Civil Wars. The bitter duel permeates every location, even the U.S. Senate Chamber where in 1856 the pro-slavery South Carolina Democrat Rep. Preston Brooks physically and viciously beat Abolitionist Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts right on the Senate floor with his gold metal-topped walking cane.

So severe were Sumner’s injuries, that it took him 3 ½ years to semi-recover and return to his desk. And Brooks? He was fined $300 (the equivalent of $10,170 in 2023), got no prison time, and was in fact re-elected.

Bold names of history like Abraham Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Henry Seward, and others are littered throughout the book. But the most interesting tidbits Taylor reports are from more minor historical characters.

Take George Bickley, a ne’er do well who failed at most jobs in his life—and married a wealthy woman who threw him out. He reinvented himself as the head of something called The Knights of the Golden Circle, going on a speaking tour to collect support and monies for “The Americanization and Southernization of the Republic of Mexico.”

As for Texas, Sam Houston pops up to argue that the state should not secede from the Union. But as Taylor notes, it was almost a country of its own, and not in a good way.

“As a frontier land crossed with a slave society, Texas was an especially violent place,” he writes. “A resident reflected that in Texas “a man is a little nearer death…than in any other country.”

In American Civil Wars, Alan Taylor looks at a very chronicled period of American history. But by weaving in the sometimes similar situations of Canada and Mexico, he presents an entire continent in a world of changes—for both better and worse.

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

- Sign out

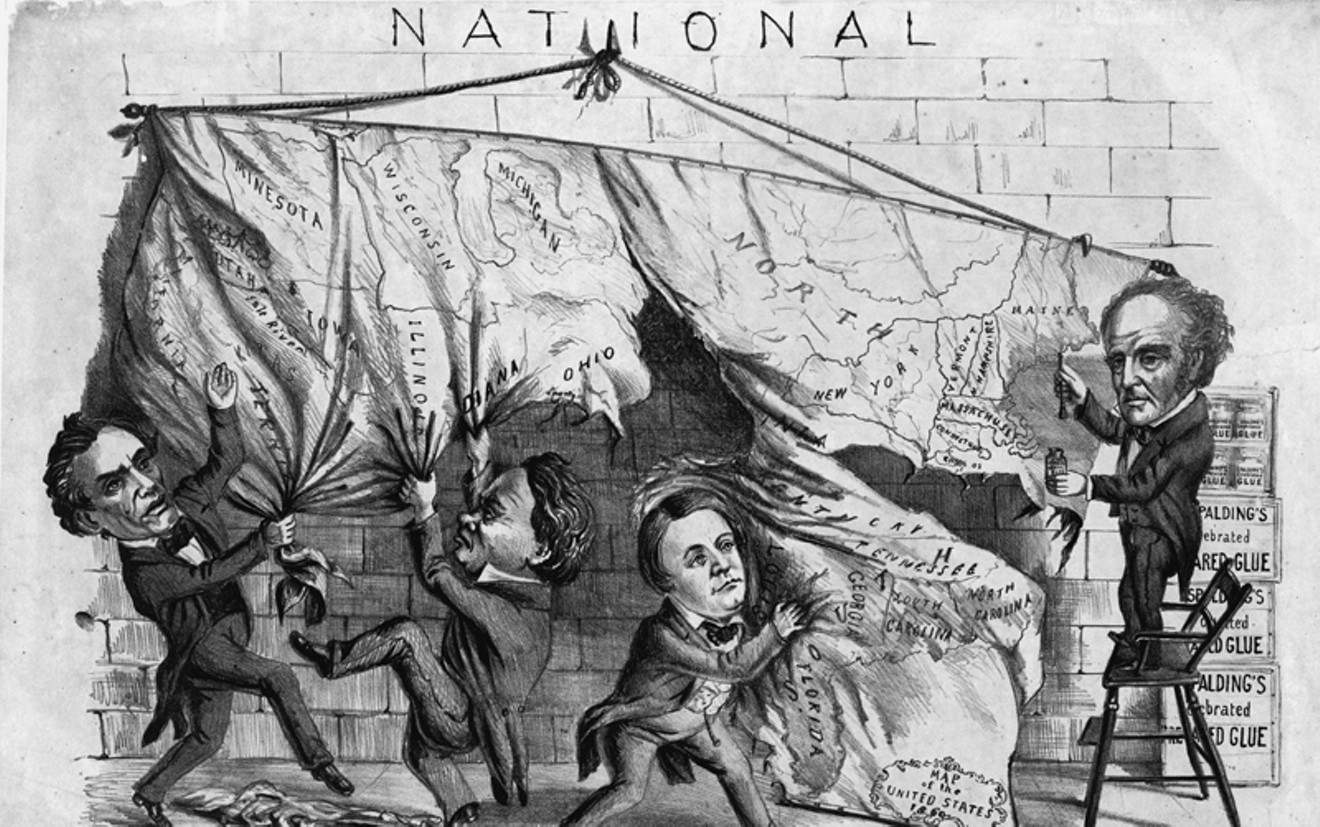

"Dividing the National Map," 1860. Presidential candidate include Abraham Lincoln, Stephen Douglas, John C. Breckenridge and John Bell.

Library of Congress

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

]

KEEP THE HOUSTON PRESS FREE...

Since we started the Houston Press, it has been defined as the free, independent voice of Houston, and we'd like to keep it that way. With local media under siege, it's more important than ever for us to rally support behind funding our local journalism. You can help by participating in our "I Support" program, allowing us to keep offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food and culture with no paywalls.

Bob Ruggiero has been writing about music, books, visual arts and entertainment for the Houston Press since 1997, with an emphasis on classic rock. He used to have an incredible and luxurious mullet in college as well. He is the author of the band biography Slippin’ Out of Darkness: The Story of WAR.

Contact:

Bob Ruggiero

Trending Arts & Culture

- Taking Steps at Main Street Theater: Prepare For a Suspension of Disbelief

- The 10 Best And Most Controversial Hustler Magazine Covers Ever (NSFW)

- Top 5 Sickest Stephen King Sex Scenes (NSFW)

-

Sponsored Content From: [%sponsoredBy%]

[%title%]

Don't Miss Out

SIGN UP for the latest

arts & culture

news, free stuff and more!

Become a member to support the independent voice of Houston

and help keep the future of the Houston Press FREE

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

The Houston Press may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Houston Press, LP. All rights reserved.