Similarly, we might expect readers of Chris Blackwell’s autobiography The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond (Gallery Books, 352 pp. $28.99) to say, “It’s good to be Chris Blackwell!” After all, he was born into a wealthy British family in 1937, grew up in Jamaica, had a bit part in Dr. No, established Island Records when he was only 22, turned the world on to reggae music, smoked ganja with Bob Marley, signed acts like Traffic, King Crimson, Roxy Music, Grace Jones, Robert Palmer, U2, and the B-52’s, and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Alas, there is no Piss Boy in Blackwell’s story, but Blackwell’s net worth is estimated to be north of $300 million, so he’s got that going for him.

Still, with material like that to work with, Blackwell and co-author Paul Morley have not come up with a very exciting book. It’s all rather superficial, the volume’s tone matter of fact to the point of occasionally becoming mundane. Probably related to the British tendency toward understatement. Nevertheless, The Islander provides valuable insights into the inner workings of Island, a boutique label that hit the big time and was, for a while, unassailably cool.

Blackwell is an intriguing individual with a distinguished lineage. His father was a member of the Blackwell family, which had owned Crosse & Blackwell, a manufacturer of condiments, marmalades, and sauces since the early 19th century. It must be mentioned, parenthetically, that seafood lovers would do well to try their cocktail sauce, which is available domestically.

Blackwell’s mother was a Jamaican heiress whose family had lived in Kingston for generations, making their fortunes in finance and agriculture. She was a close friend of Ian Fleming, the author of the James Bond novels, and said to be the inspiration for several female characters in the Bond canon, including Pussy Galore and Honeychile Rider. As Blackwell himself puts it, “There’s no two ways about it: I am a member of the lucky sperm club.”

Blackwell grew up in Jamaica, alternately hobnobbing with the ruling class and exploring the island’s native culture. A pivotal moment in his life occurred when, as a teenager, he was rescued by a dreadlocked Rastafari after running out of fuel during a boating jaunt. Blackwell was dehydrated and weak after days of walking the island’s remote coast when he saw “a tiny, lopsided wood hut held together with bits of string.” White youngsters in Jamaica were, at the time, told to avoid the Rastamen, and Blackwell was frightened, even in his desperation. “Because I had never so much as laid eyes on a Rasta, they still existed in my head as bogeymen,” Blackwell writes. “In my confused, parched state, on the verge of passing out, I looked at the man before me and thought, ‘This might be the end.’”

But that was not the case. The man gave Blackwell water and a place to sleep. When he awoke, the man, by then joined by friends, gave the youngster ital food, a vegetarian cuisine eaten by Rastas, who believed that it was a sin to kill and eat animals. “I was overcome by the incredible, almost mystic gentleness that surrounded me,” Blackwell says. “These were good men of faith. They were not burning children or plotting a violent revolution. Without hesitation, they had taken in and looked after a pale, helpless white boy who had stumbled across them and collapsed in their midst.”

After immersing himself in island culture, Blackwell dug into his trust fund and established an informal import / export business, taking Jamaican records to London, selling them, and buying British records to take back to Jamaica, where they were prized commodities. Consequently, he became a player in the music scenes of both locales, quickly moving into record production and artist management. His first hit was the Caribbean-flavored “My Boy Lollipop,” which was recorded in 1963 by Jamaican singer Millie Small and ultimately sold millions of copies in England and the United States.

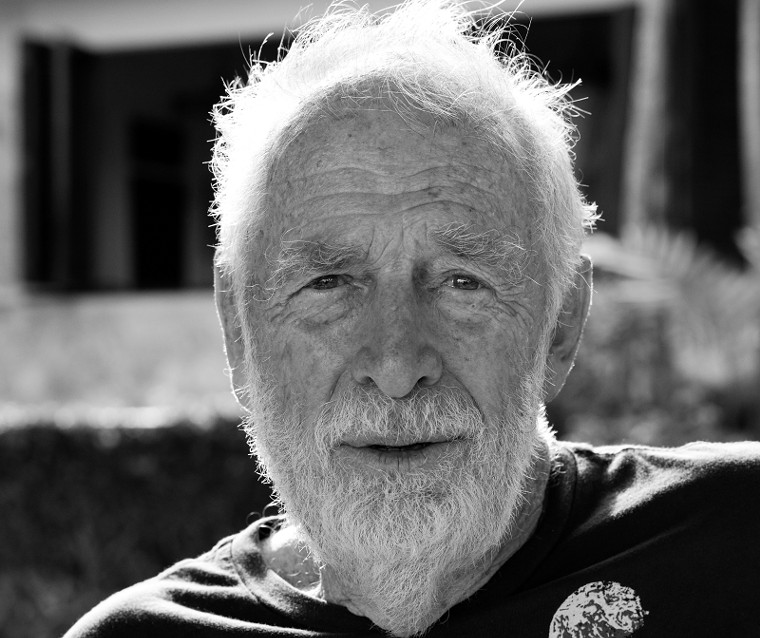

These days, media mogul Chris Blackwell spends most of his time in Jamaica, where he absorbed the island's unique culture while growing up.

Photo by Greg Williams Photography

For all of the capitalistic maneuvering in his music career, Blackwell remains - like Atlantic’s Ahmet Ertegun and Warner Brothers’ Mo Ostin - a “record man,” putting the music above all else, just as dedicated to art as to business. “Music is so beautiful when it works,” Blackwell writes, “and so frustrating when it doesn’t.” He has generally been a trailblazer, taking chances which usually pay off. With regard to Roxy Music, one of Island Records’ most significant acts, Blackwell admits that, at first, he didn’t quite understand the group’s appeal. However, he signed the band because “it was unlike anything else around at the time, which always gets my interest.”

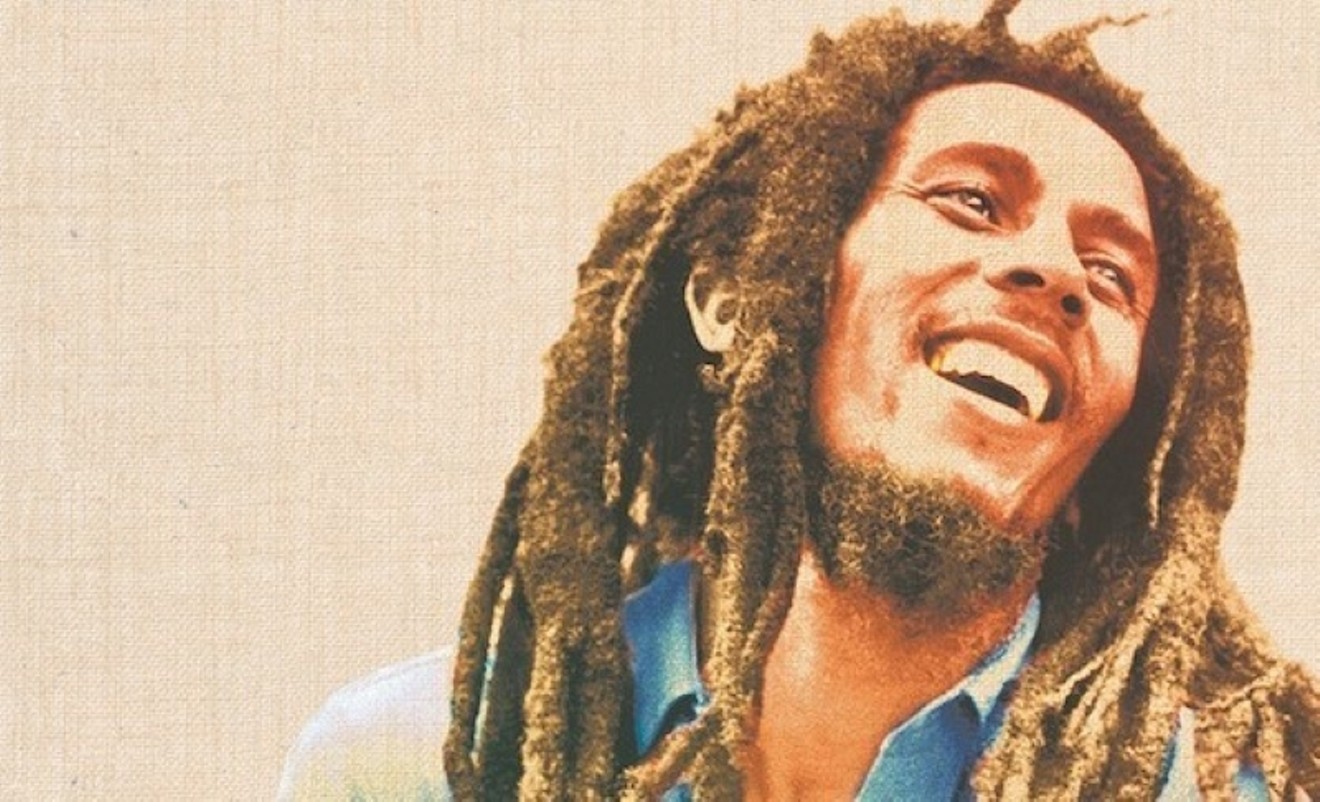

Blackwell’s most significant accomplishment was introducing the world to reggae music and culture. He first encountered Bob Marley, who would become reggae’s biggest star, when he was a member of the Wailers along with Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer. “They were immediately something else, these three – strong characters,” Blackwell writes. “As I took the measure of them, I thought, Fuck, this is the real thing.”

He explained to the band members that, in order to achieve their goal of receiving airplay in the United States, they would have to make some changes. “In that era,” Blackwell writes, “there were radio stations that played only rock music and R&B stations that played only Black music. And neither category of station played reggae.” The solution, Blackwell believed, was to “come over like a Black rock act.” Tosh and Wailer were skeptical and somewhat offended. But Marley understood the strategy and stuck with Blackwell, becoming an international star prior to his death from cancer at the age of 36. In The Islander, Blackwell addresses accusations that he exploited Marley and other reggae artists. “I never paid a Jamaican act a penny less in royalties than an English act. I was helpless without the artists. I wasn’t a singer or a writer; it made no sense to rip them off. I put my all into getting Bob’s music, and Jamaica’s music, into the mainstream,” Blackwell says.

There are plenty of big names (Miles Davis, Steve Winwood, Melissa Etheridge) sprinkled thoughout the book, along with Blackwell’s quick takes on the individuals mentioned. Of the dapper singer Robert Palmer, Blackwell notes, “Already dazzled by his looks and the fact that his clothes had no creases in them, I was even more dazzled by his voice.”

When he first met Jamaican singer and fashion icon Grace Jones, Blackwell writes, “She was the ultimate modern, ambitious representation in an infinitely connected world, of a Jamaica that came from everywhere, a Jamaica that had absorbed hippie, LSD, disco, punk, New York, Paris, Japan, London, you name it. She was an orgy of hybrids.” When U2 front man Bono is mentioned, Blackwell says of the singer’s powers of persuasion, “Bono is a very good talker.”

And ultimately, so is Blackwell. Now 85 years old, he looks back on a life that would be almost impossible to have in the current entertainment business climate, with just about every large-ish record label part of a conglomerate. After selling Island Records, he tried to work for its new parent company, but he never fit in, nor did his typical boardroom attire, a T-shirt, cargo shorts, and flip-flops. Ultimately, the strictures of corporate life proved to be too confining for the aging entrepreneur. As Blackwell says, “I like to walk my own path and answer to no one.”