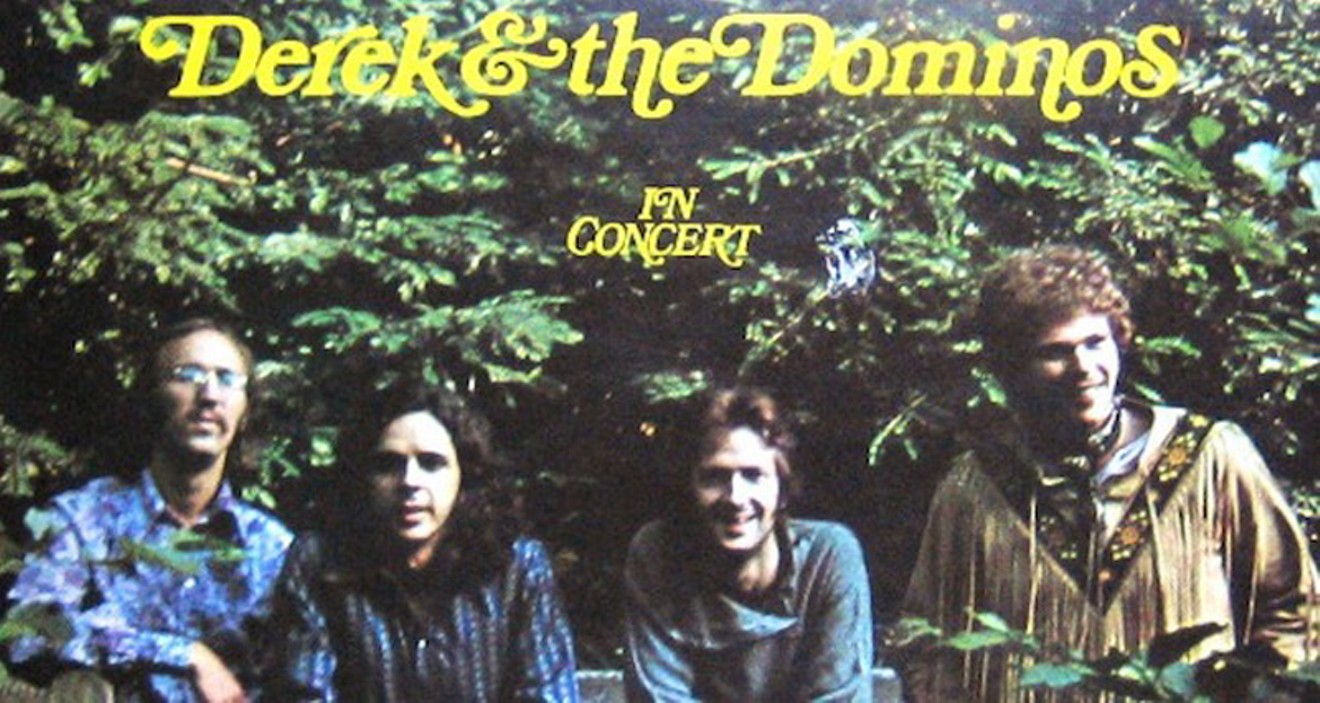

He played with three of Classic Rock’s greatest collectives: Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen and—most memorably—as one of Eric Clapton’s playing pieces in Derek & the Dominos.

As a journeyman session musician, his skin thumping can be heard on a wide-ranging array of hit singles from “God Only Knows” (Beach Boys), “Everybody’s Talkin’” (Harry Nilsson), “Power to the People” (John Lennon) and “What Is Life?” (George Harrison) to “Summer Breeze” (Seals and Crofts), “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” (Steely Dan) and “Sundown” (Gordon Lightfoot). He also played the actual beat on “The Beat Goes On” from Sonny & Cher.

But unless you’re a liner note reader, you likely don’t know the name of Jim Gordon. And if you Google him, you’ll see one shocking non-musical entry in his bio: On June 3, 1983, after suffering for years from (then undiagnosed) paranoid schizophrenia and hearing voices, he bludgeoned his 71-year-old mother with a hammer and then stabbed her to death.

The next year, he was sentenced to prison, eventually landing at the California Medical Facility. And that’s where he died in 2023 at the age of 77.

Utilizing first-hand interviews, court and medical records, and music histories, noted music journalist Joel Selvin unravels Gordon’s life, legacy, and liabilities in Drums & Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon (288 pp., $28.99, Diversion Books).

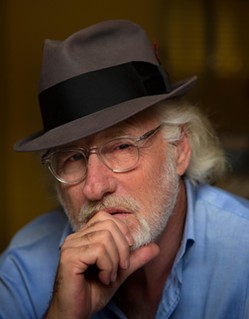

“Jim is qualified to be on any elite list of ‘Greatest Drummers’ because he expanded the vocabulary of the drums beyond belief,” Selvin says via Zoom in his home office, waving a lit cigar in hand and sitting in front of shelves of vinyl records and wall posters of old rock, R&B, and blues performers.

Jim Gordon as an 18-year-old drummer in 1964.

Gordon Family Personal Collecton/Courtesy of Amy Gordon

So in demand was Gordon for session work that it wasn’t uncommon for him to play three sessions a day, working on three to five songs per session, six days a week, for years. “He was there to make records hits,” Selvin notes. “Jim Gordon did not just keep time and hold the backbeat. Jim Gordon moved the drums into the fabric of the musical composition.”

Selvin says Gordon’s story was “lodged in his brain” for years. But it was only after an editor suggested that his next book be about “rock and roll and crime” did the writing wheels get set in motion. Four years later, he had already turned in the manuscript when he was hit with the news: Jim Gordon had died.

Selvin had previously reached out to composer and Gordon confidante Mike Post (who penned the themes to TV shows The Rockford Files and Hill Street Blues) to participate or act as a liaison to the family which included Jim’s first wife Jill and their daughter Amy, to no avail.

But the day after Gordon died, Post reached out to Selvin (who was on vacation at the time) saying that the family wanted help with putting out a press release. The experience with Selvin went well, so they decided to participate with new interviews and opened family archives for the book. It allowed Selvin to add some more depth and detail to Drums & Demons.

“They’ve all read the book, and are powerfully affected by it,” Selvin says. “Jill said she can stop beating herself up now for thinking she didn’t help Jim enough. Jim couldn’t be helped. And for Amy, this was majorly revelatory. They were all in the blast zone of this incredible trauma.”

As the years went passing by in the ‘60s into the ‘70s, Gordon began to hear voices in his head, mostly negative and full of anger and criticism (the loudest belonging to his somewhat overbearing mother). He began to have severe mood swings, and a steady, heavy diet of drugs and alcohol didn’t help.

In one infamous incident during the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour, while the troupe was partying in a hotel room, Gordon asked then-girlfriend, singer Rita Coolidge, to step out in the hallway. They “needed to talk.” She thought he was going to propose marriage.

Instead, he lashed out with an unexpected hard punch to her face, with enough force that it threw her body up against the wall before she crumpled to the ground. Returning to the party, he uttered “I just hit Rita.” The party didn’t stop, though one backup singer insisted that Coolidge be taken to the hospital. They continued their on-and-off relationship for awhile.

It wasn’t the last injustice that Gordon would inflict upon Coolidge, and it concerns perhaps his most famous recorded bit: the piano coda on “Layla,” which features both himself and Dominos keyboardist Bobby Whitlock in a composite edit. Or, if you’re a fan of the movie Goodfellas, it’s the musical background the “Dead Bodies Scene”).

Credible evidence and firsthand recollections suggest that the music was actually Coolidge’s, from her song-in-progress called “Time.” Gordon outright lifted it and to this day, the songwriting credits only name “Eric Clapton/Jim Gordon.” Selvin is not surprised that neither Clapton nor his management have ever altered the credits (and thus the royalties) in the ensuing decades.

“Jim’s outbursts of violence [with girlfriends and wives] were not like an Ike Turner thing in using violence to control a female. They were part of a roiling personality that exploded,” Selvin says. “It’s of no small irony that the rock scene was accommodating—hospitable even!—to drug addicts, alcoholics, wife beaters and sexual deviants, but they couldn’t handle someone who was genuinely mentally ill. And [Gordon’s] psychotic behavior just melted into the background.”

As the years progressed and the internal voices got louder, Gordon started losing session work due to unreliability and general angry/weird behavior while checking in and out of both medical and psychiatric facilities. He’d also go through cycles of moving all his gold records and drum kits to a dumpster by his home, vowing to get rid of them. Only to have second thoughts hours later and carry them all back inside. And repeat the process.

In his research, Selvin had to learn almost as much about mental health and medical conditions as music. And that first one gave him the biggest surprise.

“There’s one big really fucking major thing I learned, Bob. Schizophrenia occurs in one in one hundred of the general population,” he says “By comparison, multiple sclerosis is one in every ten thousand. [Schizophrenia] the flu of mental health. And half of those with it can’t respond to treatment. Those are the people sleeping under highways. And Jim’s case, it was about as severe and extreme as you can get.”

Selvin adds that in terms of the actual matricide, Jim Gordon wasn’t killing his mother so much as he was “extinguishing the voice in his head.”

“He lived in a different reality. The cacophony of voices, the headaches, the inability to bond with other people, and having no empathy or connectiveness to [other people]…it was all there.”

Selvin doesn’t think that “the needle has moved too much on treating schizophrenia” in 2024 compared to the ‘70s and ‘80s, but he notes that the recovery community is far more involved and organized. He also says there’s more awareness of the connection between mental illness and drug and alcohol use.

By the early ‘80s, the musician who played with a pantheon of Rock Gods and had every whim catered as part of the lifestyle was reduced to playing with a pickup band in a Santa Monica dive bar for $30 a night. And then, the murder.

For the author, this project has stuck with him in a way nothing else has in his entire career. “Jim’s story really got to me. I saw into his troubled heard and realized how little compassion he was shown in his life. It became really emotional for me,” Selvin sums up.

“I like my books fine, but this one has some significance that none of my other works have. As a society, as a culture, we need to deal more honestly with mental illness,” he continues.

“Jim was in this golden place. Tall, handsome, engaged to a beautiful blond dancer in California, pulling down huge money and making important records. He was scheduled to have a wonderful, happy, and extraordinary life. But it couldn’t have been taken off the rails more thoroughly, completely, and tragically than it was.”

For more on Joel Selvin, visit JoelSelvin.com