They are one of the quintessential American rock bands of the ‘70s and ‘80s, at their peak a dominating hitmaking machine and a reliable concert draw.

Even today, decades past those hits and with only 2/5ths of their classic lineup, Journey can still pack outdoor sheds and ampitheaters alone, and stadiums with other acts.

And their career and style trajectory are certainly an interesting one. From their largely Prog Rock beginnings as an offshoot of Santana, they began to turn into a radio friendly rock/pop rock machine, anchored by the keen songwriting of keyboardist Jonathan Cain and the once-in-a-lifetime wail of Steve Perry, one of rock’s greatest voices.

Oh, and they produced at one Anthem for the Ages with a little ditty about staying true to your path in “Don’t Stop Believin’.” We know that Tony Soprano dug it.

Now, Journey is the subject of not one but two simultaneously released books, including Livin’ Just to Find Emotion: Journey and the Story of American Rock by David Hamilton Golland (378 pp., $33, Rowman & Littlefield).

Golland writes that he used 2,300 primary sources (contemporary newspaper/magazine stories, interviews, videos, etc.) and secondary, historical sources to put the book together. He’s also conducted some original interviews over the years. And he does a solid, detailed job of tracking Journey’s 50+ year journey.

He also delves into how manager Herbie Herbert—who helped put the band together—ran their affairs with something of an iron fist and control. That is, until Steve Perry—hired after several records went nowhere and Herbert said they needed a true charismatic frontman/wailer. Until then, low-key keyboardist Gregg Rolie handled vocals, usually immobile behind his gear.

Perry’s exuberant stage presence, songwriting, and that voice quickly made him the focal point of the band to audience and critics alike. So, when he wanted more say over the band’s business and music direction, Herbert was shunt to the side, with the other members either signing both enthusiastically or reluctantly to Perry’s power play (though Herbert still was an equal partner in band business).

But you can’t argue with the results. Look at just the songs included just on 1981’s Escape and 1983’s Frontiers: “Stone in Love,” “Who’s Cryin’ Now,” “Open Arms,” “Separate Ways (Worlds Apart)”, “Send Her My Love,” “Chain Reaction,” “Faithfully,” and that song about Believin’.

Added to prior hits “Lovin’, Touchin’, Squeezin,’” “Wheel in the Sky,” “Lights,” “Any Way You Want It” and “Ask the Lonely,” and they had more than what the band called a “dirty dozen” of immovable, audience-pleasing setlist choices.

However, there’s one head-scratching direction the book takes. Golland—whose two previous tomes tackled the topic of race at it related to labor and then politics—posits this one as his take on race in popular culture. Here, he attempts to shoehorn the music and story of Journey in the lens of “selling” black music to white teenagers, with an undertone of purported less-than-ideal purposes.

“Like so much of what has moved American history, Journey’s popularity has to do with race [author’s italics]. It was made possible by a unique combination of Black-oriented Motown and white-oriented Progressive rock, a cultural appropriation made palatable to the white teenage audience of the post-civil rights era,” he writes. “In a modern form of minstrelsy, these white musicians safely provided ‘Black’ music to white audiences.”

Minstrelsy? That’s a hard, bizarre supposition. And Steve Perry’s professed love of the Temptations, Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke hardly transposes to him aping Black culture in a “safe” manner for white teenage (mostly) boys. If Golland thinks that Journey is geared toward selling Black music for white kids, what could he possibly think of acts like the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Rascals, Average White Band or Hall & Oates?

Even under the aegis of considering the story of Journey as a historian and not a music journalist, it’s a stretch that would make Plastic Man think twice about.

Still, with the ear of a fan and the eye of a historian, Golland does a great job chronicling all of the members’ various offshoot bands, side projects and mini-and-semi reunions. Note: their 1981 show at the Summit in Houston on the Escape tour was filmed and released as a concert special, though only in recent years has it been officially available on CD.

He also points a literary finger at Steve Perry, a recalcitrant/reluctant/reclusive rock star if there was any. And how his ego and hemming and hawing affected both the band’s initial dissolution and various latter years and subsequent reunion attempts.

When the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2017, it seems everyone in the world wanted to see Steve Perry sing with Journey for the first time in decades. Except Steve Perry. Instead, third post-Perry and current singer Arnel Pineda (who Schon found on YouTube, singing in Filipino cover band) did the honors. Though Perry did give a heartfelt speech.

However, the various lawsuits and disagreements that continue to this day. It seems that lawyers for various current and former members have been just as busy as the band’s road crew.

The classic lineup of Steve Perry (vocals), Neal Schon (guitar), Jonathan Cain (keyboards), Ross Valory (bass) and Steve Smith (drums) have all been involved in several inter-band lawsuits over songs, business dealings, corporate board positions, even the use of the name “Journey” on its own or in various incarnations. It continues to this day. Golland puts the complex legal stuff into easily digestible words.

Even Donald Trump figures into the Journey story. Cain—whose pastor wife Paula White-Cain was a spiritual advisor to 45 during his time in office—supports Trump, toured the White House with Valory and Pineda, and performed “Don’t Stop Believin’” at a political event. This drew the ire—and yet more legal action—from Schon. And Schon does himself no favors with his many shifting stories and pronouncements concerning Journey’s past, present and future.

The summer, Journey (whose actual current lineup is somewhat in flux) will hit sports stadiums across America again, this time with a bulletproof nostalgia-drenched Def Leppard and a rotating opener of Heart, Cheap Trick or the Steve Miller Band.

Livin’ Just to Find Emotion makes for a great homework reading assignment. And extra points if you know there’s no such place—to quote a certain Classic Rock Anthem—as “South Detroit.”

Support Us

Houston's independent source of

local news and culture

account

- Welcome,

Insider - Login

- My Account

- My Newsletters

- Contribute

- Contact Us

- Sign out

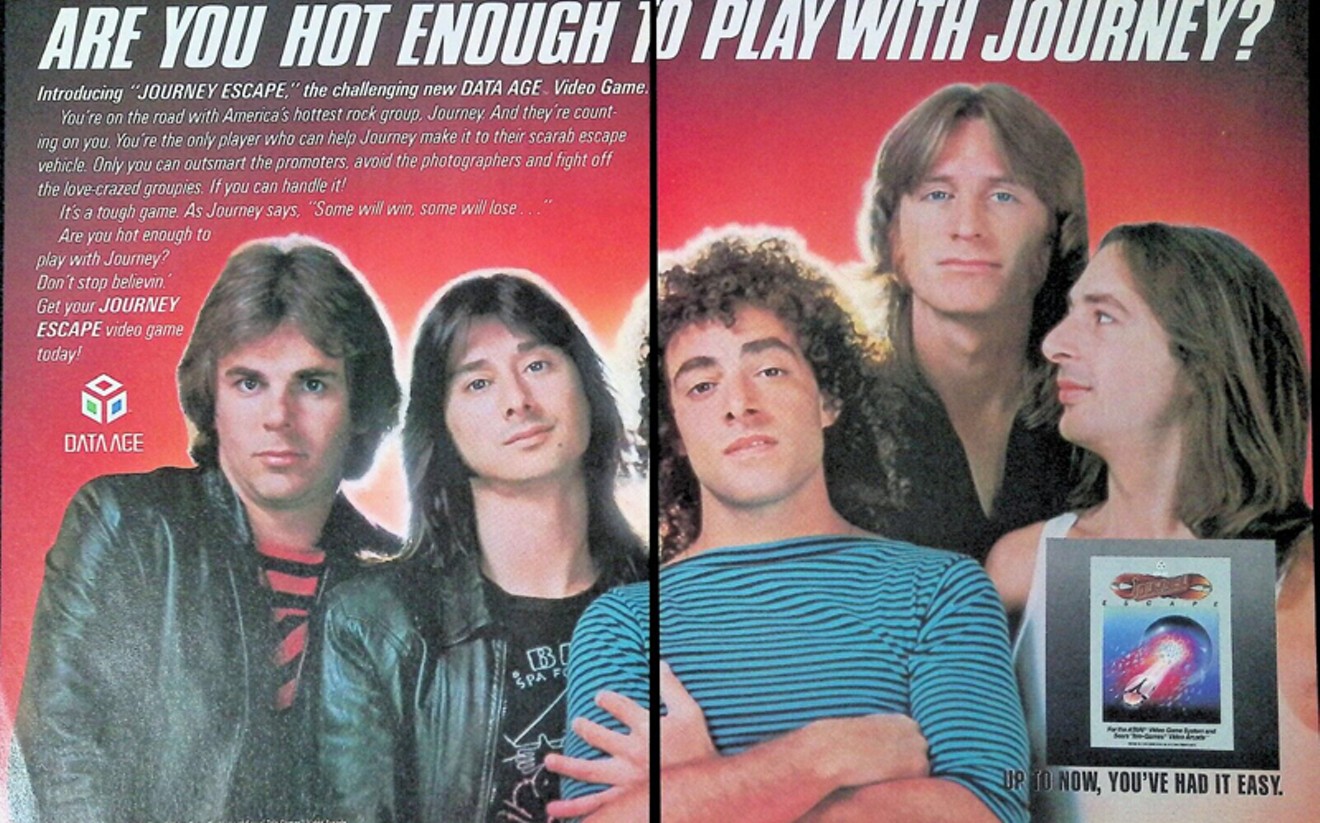

Who remembers that Journey had their own video game—in both arcade and home versions! According to actual promotional copy, players had to "escape" from "Love-Crazed Groupies, Sneaky Photographers, and Shifty-eyed Promoters." L to R: Jonathan Cain, Steve Perry, Neal Schon, Ross Valory and Steve Smith.

Magazine advertisement

[

{

"name": "Related Stories / Support Us Combo",

"component": "11591218",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Air - Billboard - Inline Content",

"component": "11591214",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7"

},{

"name": "R1 - Beta - Mobile Only",

"component": "12287027",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size 2",

"component": "11591215",

"insertPoint": "4th",

"startingPoint": "16",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

}

]

KEEP THE HOUSTON PRESS FREE...

Since we started the Houston Press, it has been defined as the free, independent voice of Houston, and we'd like to keep it that way. With local media under siege, it's more important than ever for us to rally support behind funding our local journalism. You can help by participating in our "I Support" program, allowing us to keep offering readers access to our incisive coverage of local news, food and culture with no paywalls.

Bob Ruggiero has been writing about music, books, visual arts and entertainment for the Houston Press since 1997, with an emphasis on classic rock. He used to have an incredible and luxurious mullet in college as well. He is the author of the band biography Slippin’ Out of Darkness: The Story of WAR.

Contact:

Bob Ruggiero

Trending Music

- Top 10 Butt-Rock Bands of All Time

- The Rolling Stones At NRG Stadium Was One Great Party Last Night

- Duran Duran Brings Planet Earth To The Woodlands

-

Sponsored Content From: [%sponsoredBy%]

[%title%]

Don't Miss Out

SIGN UP for the latest

Music

news, free stuff and more!

Become a member to support the independent voice of Houston

and help keep the future of the Houston Press FREE

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of our

terms of use,

our cookies policy, and our

privacy policy

The Houston Press may earn a portion of sales from products & services purchased through links on our site from our

affiliate partners.

©2024

Houston Press, LP. All rights reserved.