In Texas, the term brings to mind one man: Willie Nelson. Who, for more than half a century now, (give or take a few years of inactivity) has served as both headliner and grizzled ringmaster to the Willie Nelson Fourth of July Picnic. An all-day (or even multi-day) party where he invites some of his buddies to pick and sing a bit for the people.

The Picnics have run the gamut from barely contained, loose-running parties of beer, drugs, and naked people (lots of naked people) planted on a boiling hot dirt or grass field with few amenities to professionally run indoor shows that run like clockwork and charge for water.

The colorful history of Willie’s still-ongoing patriotic parties are detailed exhaustively and entertainingly in Dave Dalton Thomas’ new book Picnic: Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Tradition (304 pp., $35, Texas A &M University Press). Thomas will discuss the book and sign copies at Brazos Bookstore on May 23.

Dalton—who has been researching the Picnic for two decades, been to almost every one since 1995, and conducted more than 150 original interviews for the book from performers, organizers, and attendees to local officials, crew, and promoters. In fact, he may in fact be the one person destined to chronicle its history.

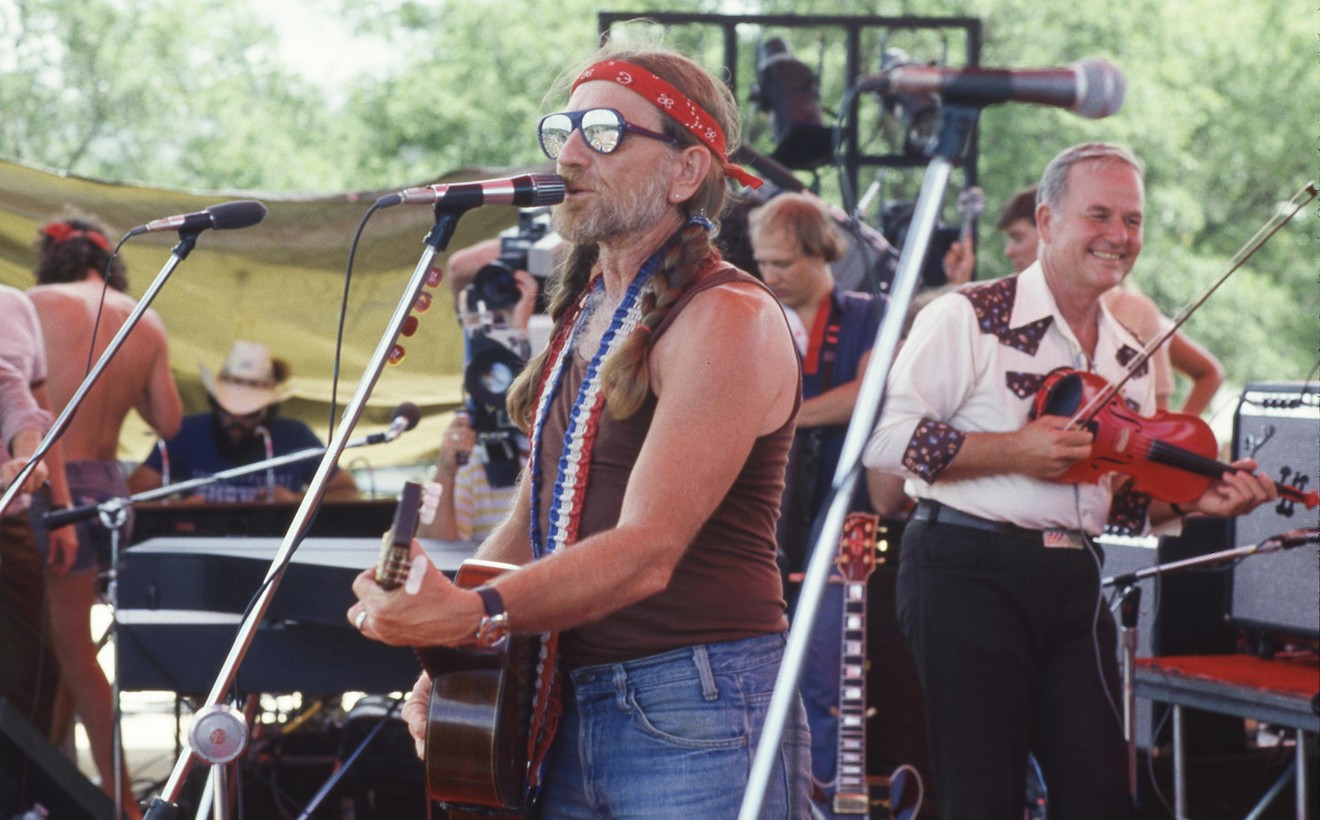

Willie Nelson, Kenneth Threadgill and Leon Russell perform during the 1973 Picnic.

Photo by Watt Casey

Patoski, a legendary Texas music scribe, did write Picnic’s forward. “But it just seems that nobody loved this thing like I did. People have described [writing the book] as torture, but I thought it was fantastic. So maybe I was born to write this!”

Of the interviews, Thomas says things unfurled almost like a spider web in how after talking to one person, they’d tell him he should also talk to someone else—and even made introductions or vouched for him. Sometimes, recollections of the same Picnic or event varied wildly depending on who was telling the story.

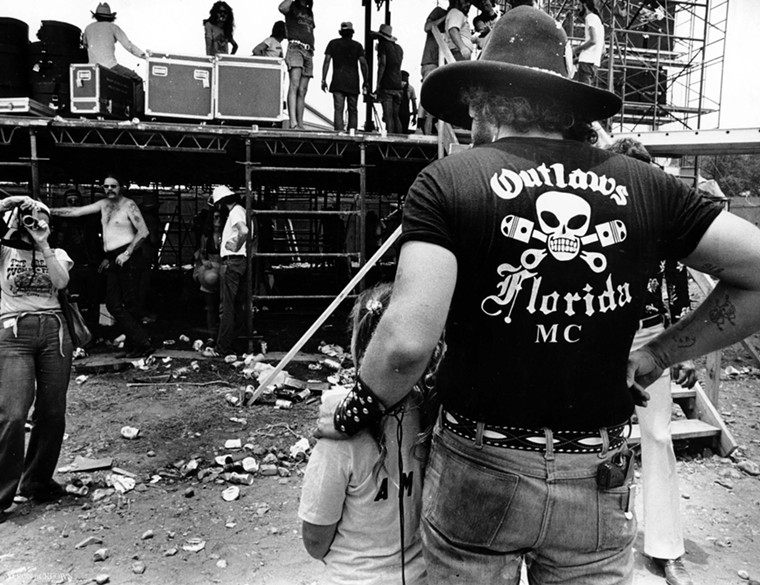

A cowboy watches the growing crowd at the inaugural 1973 Picnic. Local volunteers kept an eye on the proceedings and occasionally rounded up naked hippies.

Photo by and © Ron McKeown

So, an estimated 40,000 people watched sets by Nelson, Leon Russell, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, Rita Coolidge, Charlie Rich, Billy Joe Shaver, and more (with a number of those names appearing time and time again in the future).

Thomas writes that many Picnics of the first decade were very loosely run, usually by Willie and his crew and with no shortage of shady associates (sometimes toting guns) and very liberal views of concert aspects like set times, crowd control, concessions, money collection and operations.

Performers didn’t even have contracts and would often be paid in cash by Willie or his associates on the bus according to whim and turnout (though by most accounts, Willie made sure others were paid, even if he wasn’t or lost money). There were also shady advisors, businesspeople with agendas, and hangers on who might catch Willie’s ear. That had its pros and cons.

“I think it was much more adventurous in the early days. People who were prepared to handle that sort of thing had more fun. People that weren’t did not have fun,” Thomas says.

“Look at the 1976 Picnic in Gonzales. They didn’t have enough sanitation. And for hippie guys, it wasn’t that big of a deal, you’d just pee behind a tree. But for the female fans, it was a lot bigger deal,” he continues.

“Not having the structure to support the amount of people coming was definitely a drawback. But today, people who were there remember the adventure. And things became a legend as soon as it happened.”

And indeed, modern perceptions of those earlier Willie Picnics—like Woodstock—exist somewhere between the confluence of mythical fond, fuzzy memories and the realities of the situation. Especially some of the lawlessness.

“Willie has done his best to encourage the myth of how great everything was, and that’s certainly important. It’s part of our common mythology as Texans. And you could still go to a Picnic a few years ago at the $400 million racetrack in Austin and still feel a connection to that rocky ranch in Dripping Springs,” Thomas says.

The 1976 Picnic at Gonzales was the first—though not the last—to face pushback from the local community who did not want the chaos, traffic, and drug influx of the event (and those naked people!) in their fine town. A group called—amazingly—CLOD (Citizens for Law, Order & Decency) tried to stop it. Other cities would say, accurately, that the Picnics violated the Texas “Mass Gathering Act” which required permits and payments.

David Allan Coe poses for a photo backstage at the Gonzales Picnic. He was seen with the gun in his back pocket throughout the day.

Photo by and © Ron McKeown

Some Picnics were even held in far-flung U.S. cities like Kansas City, Tulsa, Syracuse, and Atlanta. Though the line between a “Picnic” and a regular or special concert gets blurred. Like in 1986 when it was “held” as Farm Aid II.” According to Thomas’ stats for the shows that released them, Picnic attendance ranged from 4,000 to 80,000 often heat-stroked attendees (and yes, Texas’ boiling outdoor summer temperatures are something of a recurring motif).

Houston hosted the Picnic once in 2008, while Houston-based promoters PACE Concerts and Louis Messina were involved in the 1978 (aka the Texxas Jam), ’84, and ’85 events. By which time things were run by professionals in the concert industry and not Willie’s poker-and-beer buddies. That also meant more rules and regulations.

“Having security and people fenced in kind of tamed the Picnic a bit, but I’ve had people tell me that Willie did that intentionally. He was a mega-star and could not devote the time to all the lawsuits from the raging problems they had in the early ‘70s,” Thomas says.

Even the term “Picnic” was malleable. Thomas quotes John Kolsburn of Houston who said of the ’84 event “They call it a picnic, but you can’t bring anything to eat. It’s ridiculous.”

“I’ve heard a quote like that many times!” Thomas laughs.

In his intro, Thomas laments the Picnic performers he was not able to speak with for the book who have since passed away like Jerry Jeff Walker, Johnny Bush and Billy Joe Shaver. He also attempted to talk to Willie himself but was never able to get past his publicists and gatekeepers or receive responses.

Since Picnic came out last month, he hasn’t heard anything—positive or negative—from Official Willie World. And he adds that he was honest about some of the negative issues and aspects that he uncovered during the course of his research.

Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard shared the stage on the first day of the two-day 2003 Picnic.

Photo by Gary Miller

One person who, unfortunately, won’t be in attendance this year is Dave Dalton Thomas. The guy who literally wrote the book.

“I’m a former newspaper copy editor who now works for the state and has a family with three kids,” he says wryly. “I can’t afford a ticket to New Jersey!”

Dave Dalton Thomas will discuss Picnic: Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Tradition and sign copies at 6:30 pm on Thursday, May 23, at Brazos Bookstore, 2421 Bissonnet. For more information, call 713-523-0701 or visit BrazosBookstore.com. Free, but books must be purchased from Brazos to be signed.